Extrachromosomal DNA in Cancer Genomics

Published in Genetics & Genomics and General & Internal Medicine

Introduction

Cancer genomics has traditionally been framed around chromosomal mutations single nucleotide variants, copy number alterations, translocations, and structural rearrangements embedded within linear chromosomes. However, a paradigm-shifting discovery has redefined this view: extrachromosomal DNA (ecDNA).

Unlike chromosomal DNA, ecDNA exists as circular, acentromeric DNA fragments outside canonical chromosomes, frequently harboring amplified oncogenes. Their presence fundamentally alters tumor evolution, heterogeneity, and therapeutic resistance.

What is Extrachromosomal DNA (ecDNA)?

Extrachromosomal DNA refers to circular DNA molecules that:

-

Lack centromeres.

-

Replicate independently of chromosomes.

-

Segregate randomly during mitosis.

-

Frequently contain amplified oncogenes.

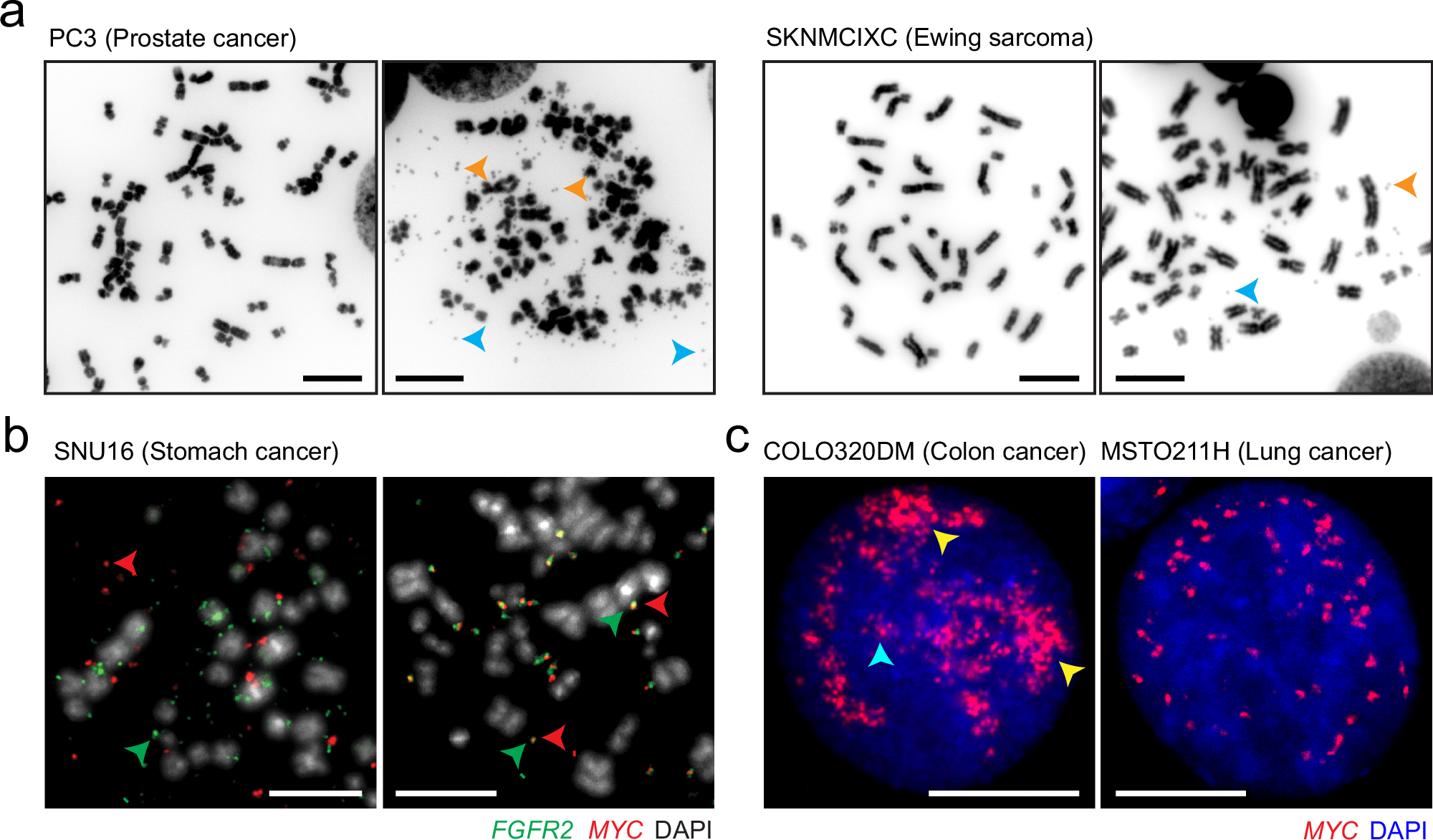

Historically, ecDNA was observed cytogenetically as double minutes (DMs) small, paired chromatin bodies seen in metaphase spreads. These structures were initially considered rare anomalies. Today, they are recognized as central drivers in aggressive malignancies.

Mechanisms of ecDNA Formation

Multiple genomic instability processes contribute to ecDNA biogenesis:

1. Chromothripsis

Catastrophic chromosomal shattering followed by aberrant reassembly can generate circular DNA fragments.

2. Breakage–Fusion–Bridge (BFB) Cycles

Telomere dysfunction initiates cycles of chromosomal breakage and fusion, ultimately yielding amplified circular DNA.

3. Replication Stress and DNA Repair Dysregulation

Aberrant homologous recombination or non-homologous end joining may facilitate circularization of genomic segments.

These processes are hallmarks of genomic instability an enabling characteristic of cancer.

Oncogene Amplification on ecDNA

ecDNA frequently carries high-level amplifications of oncogenes such as:

-

MYC.

-

EGFR.

-

MDM2.

-

CDK4.

Unlike chromosomal amplification (e.g., homogeneously staining regions), ecDNA enables:

-

Massive copy number gains.

-

Ultra-high transcriptional output.

-

Enhanced chromatin accessibility.

-

Dynamic modulation under therapeutic pressure.

This leads to oncogene overexpression beyond what linear chromosomal amplification can achieve.

ecDNA and Tumor Evolution

One of the most profound consequences of ecDNA biology is its non-Mendelian segregation during mitosis.

Because ecDNA lacks centromeres:

-

It distributes unevenly between daughter cells.

-

Rapidly generates intratumoral heterogeneity.

-

Accelerates Darwinian selection.

Under therapeutic pressure, cells with higher ecDNA copy numbers can be positively selected, driving resistance. Conversely, ecDNA copies can decrease when selective pressure is removed—demonstrating a reversible, adaptive genomic system.

This dynamic regulation represents a novel layer of cancer plasticity.

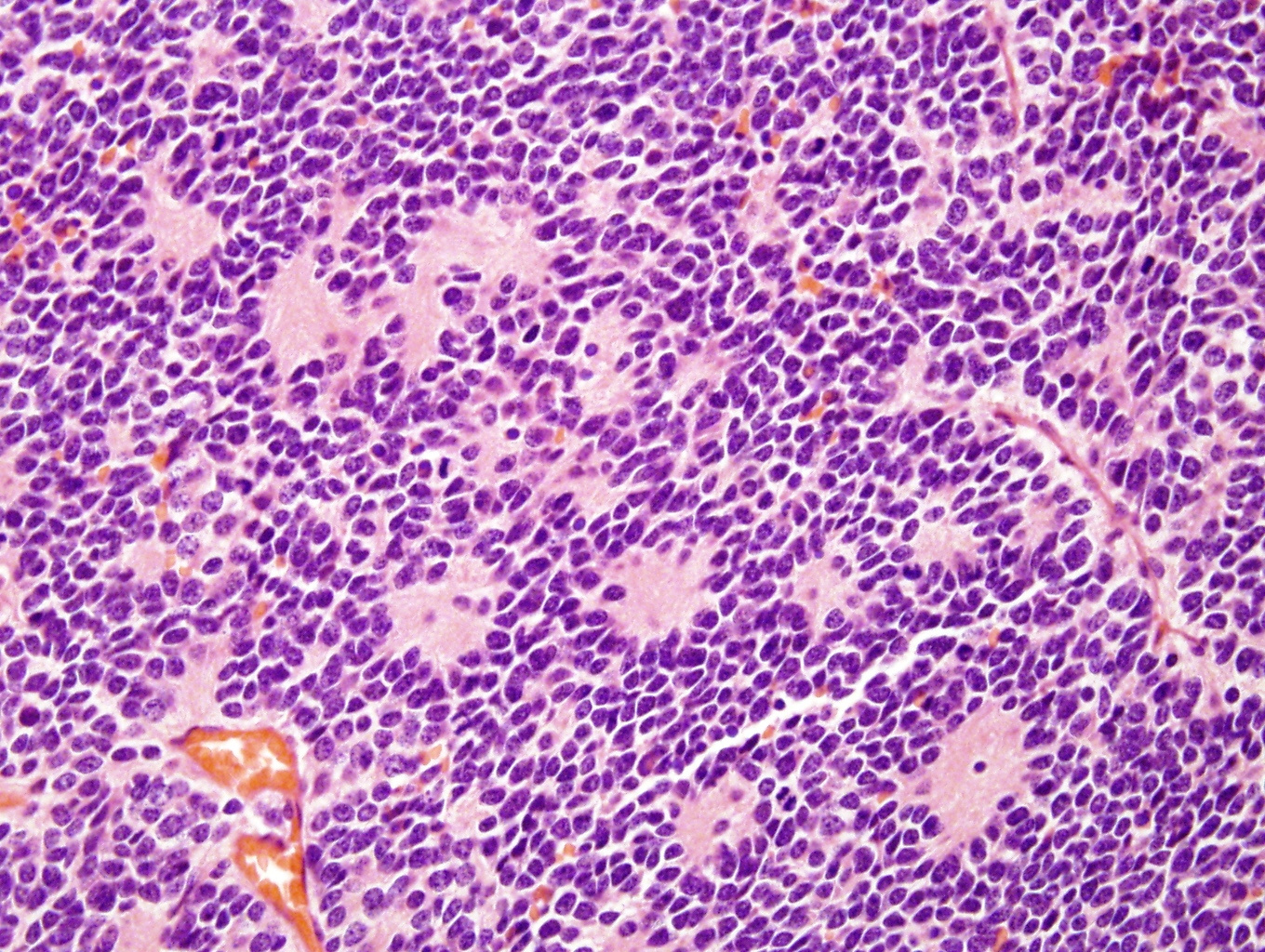

ecDNA in Specific Malignancies

ecDNA is highly prevalent in aggressive tumors, including:

-

Glioblastoma.

-

Neuroblastoma.

-

Non-small cell lung carcinoma.

-

Colorectal cancer.

In glioblastoma, ecDNA-mediated amplification of EGFR is particularly well characterized, contributing to therapeutic resistance and aggressive progression.

Epigenomic and 3D Genome Implications

ecDNA is not merely amplified DNA it is epigenetically active.

Recent chromatin conformation studies demonstrate that ecDNA:

-

Forms hubs of regulatory interactions.

-

Enhances enhancer–oncogene contacts.

-

Rewires 3D genome architecture.

This creates transcriptional hyperactivation domains, further amplifying oncogenic signaling.

Detection and Analytical Approaches

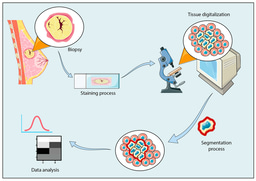

Modern molecular pathology has enabled ecDNA detection through:

-

Whole-genome sequencing (WGS).

-

Optical mapping.

-

ATAC-seq.

-

FISH and metaphase cytogenetics.

-

Circle-seq and AmpliconArchitect algorithms.

Integration of bioinformatics pipelines is essential to distinguish ecDNA from linear amplifications.

For molecular diagnostic laboratories, recognizing ecDNA-associated patterns in copy number variation data is increasingly important.

Therapeutic Implications

ecDNA introduces new therapeutic challenges and opportunities:

Challenges

-

Rapid adaptive resistance.

-

High oncogene dosage.

-

Tumor heterogeneity.

Emerging Strategies

-

Targeting ecDNA replication mechanisms.

-

Disrupting enhancer–oncogene interactions.

-

Exploiting replication stress vulnerabilities.

-

Inhibiting DNA damage response pathways.

Because ecDNA lacks centromeres, strategies targeting mitotic segregation dynamics are also under investigation.

Clinical and Precision Oncology Relevance

From a precision medicine standpoint, ecDNA explains why:

-

Some tumors show extreme oncogene amplification without proportional chromosomal gain.

-

Resistance emerges despite initial targeted therapy response.

-

Copy number variation appears highly dynamic over time.

For molecular pathologists and genomic oncologists, ecDNA represents a shift from static genomic models to adaptive structural genomics.

In future clinical workflows, ecDNA characterization may:

-

Stratify high-risk patients.

-

Predict resistance patterns.

-

Guide combination therapy selection.

The Future of Cancer Genomics

Extrachromosomal DNA redefines oncogene amplification as a mobile, plastic, and evolutionarily optimized system.

Rather than being confined to chromosomal architecture, cancer genomes can externalize growth-driving sequences into autonomous, rapidly evolving units.

As research advances, ecDNA may transition from a genomic curiosity to a routine biomarker in molecular oncology reshaping diagnostics, prognostication, and therapeutic design.

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in