Hidden Chemistry in Winter Haze: How Aerosol Water Drives New Pollutant Formation

Published in Earth & Environment

The story of this study begins with a question we couldn't ignore: what are we really breathing in, beyond what we can see or smell?

Over the past decade, global chemical production and use have grown rapidly. Alongside this trend, concerns have been mounting over chemicals of emerging concern (CECs), which often fall outside regulatory scopes but dwell in the environment and may bring forth long-term health risks.

Once released into the atmosphere, these chemicals don’t just float passively. The air is full of energy: sunlight, oxidants, and particles all working together like a giant chemical reactor. A single molecule can transform, break down, recombine, or even turn into something more harmful.

Yet much of this transformation remains invisible, not just to the eye but to science. Most environmental risk assessments still focus mostly on what’s emitted, while little on what’s formed afterward, or the transformation products (TPs).

That’s where our journey began.

Funded by China’s National Key R&D Program, led by Prof. Gan Zhang (张干), we were able to set out to build a comprehensive picture of hazardous air pollutants (HAPs) across China’s major cities. Our team travelled across 18 cities, setting up 28 sampling sites from the industrial north to the subtropical south. Over months of fieldwork, we collected more than a thousand air samples, capturing both gaseous and particle-bound pollutants, from urban rooftops and city edges (Figure 1). Each cartridge, each filter, represented a snapshot of invisible chemistry in the real ambient atmosphere.

Figure 1 High-volume air samplers ready for shipment to a nationwide network of atmospheric monitoring sites. Insets show selected sampling locations across China.

What we found was striking. Among the many pollutants, organophosphate esters (OPEs), commonly used as flame retardants, stood out for their much higher abundance than other organic contaminants. OPEs have been quietly replacing the ‘older’ brominated flame retardants in many consumer products, from electronics to furnishings. But unlike their predecessors, they are highly mobile and variable.

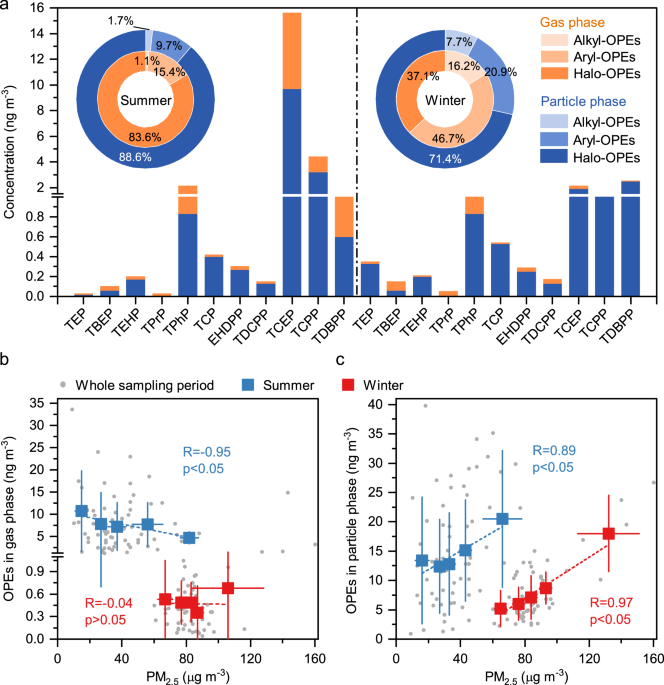

In our samples, OPEs showed a rapid rise in concentration over recent years. More surprisingly, many of them were not occurring freely in the gas phase—they were hiding in PM2.5 particles, where they can be easily inhaled deep into the lungs and potentially enter the bloodstream, raising concerns about their effects on human health beyond the respiratory system.

This raised an urgent question: why are some OPEs so prone to sticking to particles, especially the hydrophilic ones?

To find out, we zoomed in on data from 9 cities across the Pearl River Delta and beyond. We observed that the particle partitioning of OPEs was not solely determined by their functional groups, but was largely influenced by their interactions with complex aerosol mixtures. Hydrophobic OPEs aligned well with model predictions and were linked to the organic content of particles. Hydrophilic OPEs, however, behaved differently. Their particle-phase concentrations were much higher than model predictions. These hydrophilic compounds showed strong correlations with aerosol liquid water — microscopic droplets that form in PM2.5 during humid, polluted conditions. Even accounting for this water, the observed levels remained surprisingly high.

This big gap between observation and prediction led to a following question: could some hydrophilic OPEs be chemically forming inside aerosol?

A clue came from experimental studies showing that certain OPEs can form as transformation products (TPs) of organophosphate antioxidants (OPAs), a class of compounds that are also widely used in manufacturing with high global production volume of total OPAs (up to 100,000 tons per year). OPAs themselves were nearly undetectable in our ambient samples, yet their ‘fingerprints’ appeared in the form of newly formed OPEs.

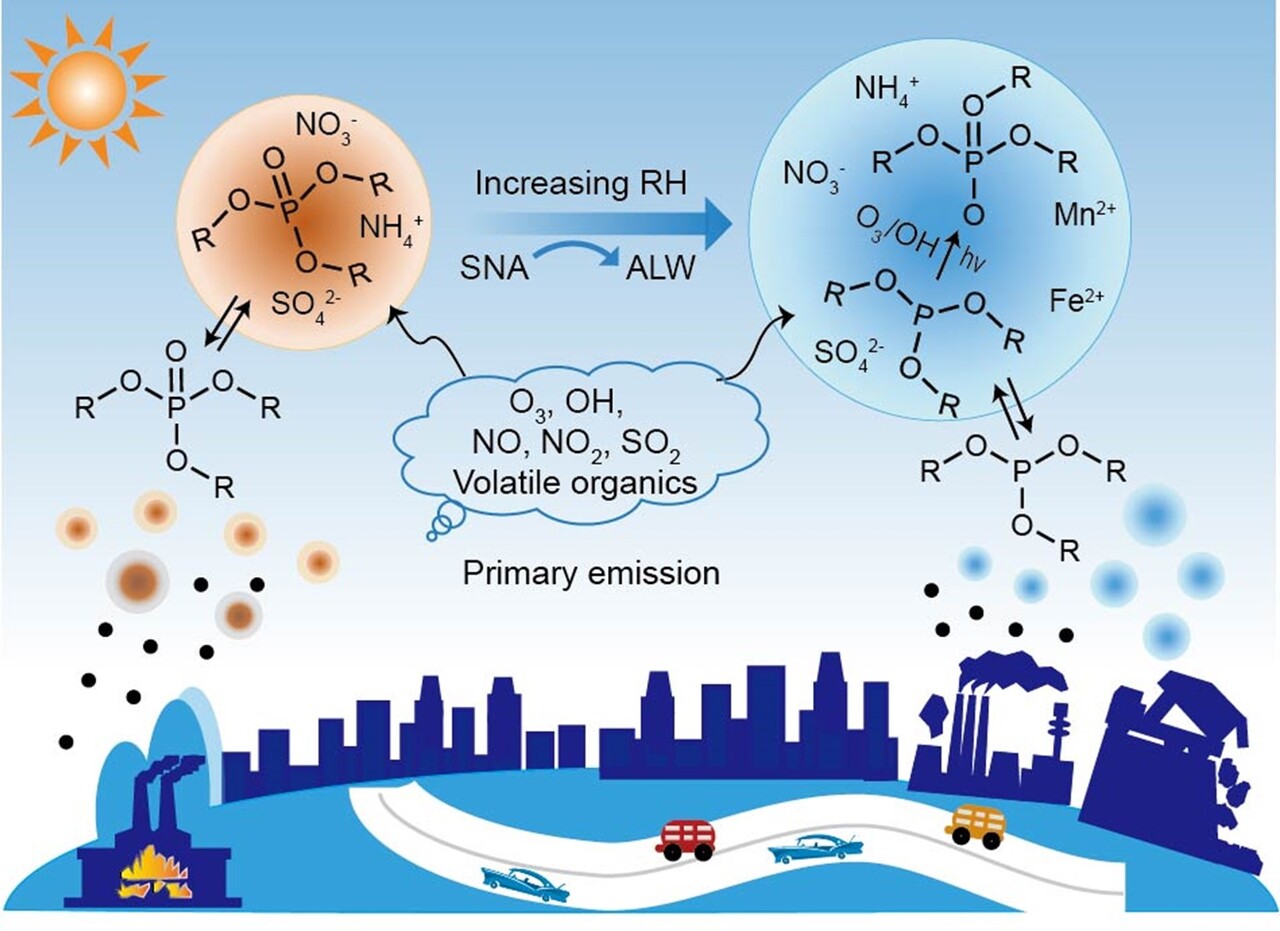

We hypothesized that OPAs might be undergoing aqueous-phase oxidation inside atmospheric particles, a mechanism that had never been confirmed in real-world air. Our dataset gave the evidences: under high humidity and elevated levels of sulfate, nitrate, and ammonium, conditions typical in Chinese winter smog, aerosol liquid water served as the reactor. Dissolved iron and manganese likely accelerated the process, generating reactive oxygen species that converted OPAs into OPEs right in the midair.

In essence, we had caught the atmosphere in the act of creating new pollutants. This raised a broader question: how much of these pollutants were being formed in the air, and how much came from direct emissions?

Using molecular markers and source apportionment models, we quantified the seasonal sources of particle-bound hydrophilic OPEs in several Chinese cities. Direct emissions dominated during the summer, accounting for over 80 %. But in winter, the contribution from secondary formation increased sharply, reaching as high as 25 -50%.

The finding challenges conventional thinking, that OPEs in PM2.5 are not solely derived from direct emissions; they can also form through aqueous-phase chemical reactions within atmospheric particles. This highlights secondary aqueous-phase formation as a key but often overlooked pathway substantially contributing to the toxic burden of urban air, especially under humid and polluted scenarios such as winter haze.

As global temperatures rise and urban air becomes more chemically reactive, this secondary formation pathway may become even more significant. It is time for chemical risk assessments to move beyond direct emissions and take into account the complex chemistry unfolding within atmospheric particles. What matters is not only what we emit, but also how the atmosphere modifies.

For us, this work is more than just a dataset. It is thousands of hours in the field and in the lab, from carrying samplers through narrow alleyways to checking filters in the freezing cold, and checking mass chromatograms on the computer screens. But it also reflects a growing sense of urgency. If we don’t understand how these pollutants behave and evolve in the atmosphere, we would not be able to fully protect ourselves from the chemicals.

Follow the Topic

-

Nature Communications

An open access, multidisciplinary journal dedicated to publishing high-quality research in all areas of the biological, health, physical, chemical and Earth sciences.

Related Collections

With Collections, you can get published faster and increase your visibility.

Women's Health

Publishing Model: Hybrid

Deadline: Ongoing

Advances in neurodegenerative diseases

Publishing Model: Hybrid

Deadline: Mar 24, 2026

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in