Hidden Viral Worlds Beneath Our Feet: Discovering the Invisible Architects of Groundwater Ecosystems

Published in Ecology & Evolution and Microbiology

Diversity and ecological roles of hidden viral players in groundwater microbiomes

Why Groundwater Matters

Groundwater is Earth's largest reservoir of unfrozen freshwater. The integral parts of terrestrial ecosystems and a critical component of global biogeochemical cycles. It sustains rivers, supports agriculture, and provides drinking water to billions. Yet the microbial life in groundwater remains one of the least explored frontiers on our planet.

The microbes living in groundwater are doing more than just surviving. They're thriving. At groundwater, carbon fixation by chemolithoautotrophs reaches up to 10% of rates measured in oligotrophic ocean surface waters. Pretty remarkable for a light-deprived, low-biomass environment. These microbes turn inorganic carbon into organic matter in complete darkness, forming the base of an entire subsurface food web.

But what role do viruses play in this hidden ecosystem? In oceans, viruses lyse cells, transfer genes, and reprogram microbial metabolism. Could they be doing the same underground?

Groundwater: A Living Laboratory

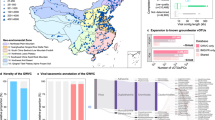

The Hainich Critical Zone Exploratory (CZE) groundwater, in Thuringia, Germany, is more than just a field site. For over a decade, researchers have monitored everything from nutrient chemistry to microbial community structure. A 6 km hillslope 11-13 groundwater wells span a remarkable gradient from oxygen-rich to oxygen-depleted conditions (for this study, we focused only on seven wells).

What makes Hainich particularly compelling as a study site is that through over a decade of paired surface and subsurface sampling, we can observe the signatures of extreme weather events on the system. Increasing precipitation and declining water levels have altered the system. Dissolved organic matter has shifted toward a more soil-like molecular fingerprint. The adsorption and transport capacity of the soil-to-groundwater pathway appears to be compromised. More surface-derived organic matter is reaching groundwater, with important implications for water quality and microbial communities. In this dynamic context, we asked: How do viruses fit into this changing ecosystem?

The Unexpected Abundance

I'll admit, I started this project with modest expectations. Groundwater has notoriously low biomass. The environment is dark, cold, and nutrient-poor. With so few microbes, I thought, how many viruses could there really be? The answer: millions, ~2 M virus operational taxonomic unit/vOTUs (≥ 1 kb).

When we analyzed 1.24 terabases of metagenomic sequence data from the Hainich, we uncovered over, millions, of which 257,000 distinct vOTU (≥ 5 kb). And 99% of them were completely novel. We found more viral diversity in this single groundwater system than has been cataloged in most other freshwater environments combined. Opening a door to a hidden world that had been there all along, just waiting beneath our feet.

What We Learned: Groundwater Virosphere

The diversity was just the beginning. When we connected viruses to their hosts, we found something unexpected. Groundwater virus-host interactions are far more complex than simple one-on-one relationships.

The groundwater teems with ultrasmall organisms. Members of the Candidate Phyla Radiation (CPR) bacteria and DPANN archaea could reach up to 50% of the microbial community. These mysterious microbes have streamlined genomes and can't survive alone. They rely on close associations with other bacteria or archaea. Our data revealed that these ultrasmall organisms are themselves infected by specialized viruses. Picture multiple layers of interaction: host bacteria support CPR/DPANN symbionts, which are in turn infected by viruses. A Russian doll of dependencies we're only beginning to untangle.

Perhaps most intriguing were the genes carried by these viruses. Having studied viruses across diverse ecosystems (soils, oceans, rumen guts, permafrost), I can say that groundwater viruses carry a uniquely tailored metabolic toolkit. Unlike soil viruses, they don't carry genes for breaking down complex plant-derived carbon. Instead, they're equipped with genes for carbon fixation and central carbon metabolism. Functions that make sense where organic matter is scarce and autotrophy dominates. We identified 3,378 viral populations carrying auxiliary metabolic genes (AMGs) linked to carbon, nitrogen, and sulfur cycling. Molecular tools that could reprogram host metabolism during infection.

Why This Matters Beyond the Lab

Understanding viruses in groundwater has real implications for predicting how these critical ecosystems will respond to environmental change. As climate change alters precipitation patterns and groundwater levels, microbial communities will shift. And viruses will influence those shifts. They'll influence which populations thrive or decline, how efficiently nutrients cycle, and ultimately, the quality and availability of groundwater resources that billions depend on.

Our findings provide a baseline against which future changes can be measured. They generate testable hypotheses: Are multi-layer virus-host interactions stable under changing conditions? How do viral-encoded metabolic genes influence carbon storage versus release? As groundwater becomes more influenced by surface inputs, will viral communities shift accordingly? These questions matter because groundwater isn't isolated. Connected to surface waters, soils, and human activities. Understanding the invisible viruses beneath our feet brings us closer to predicting and managing these essential water resources in a changing world.

A Transatlantic Partnership

This research was made possible through sustained support from the Cluster of Excellence “Balance of the Microverse” at Friedrich Schiller University Jena, a competitive excellence grant renewed for a second term that provided the resources to explore these questions in depth. Additional funding was provided by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG) through Germany’s Excellence Strategy (EXC 2051, Project-ID 390713860) and the Collaborative Research Centre AquaDiva (CRC 1076, Project-ID 218627073), with further support from the U.S. Department of Energy (award #DE-SC0023307).

This work also represents a true meeting of expertise. The collaboration between Friedrich Schiller University Jena and The Ohio State University brought together two essential perspectives: Kirsten Küsel's deep knowledge of groundwater microbiology and biogeochemistry, cultivated through years at Hainich, and Matthew Sullivan's pioneering approaches in viral ecology and bioinformatics, developed through global-scale of ocean virome studies. Understanding both the ecosystem and the viruses allowed us to move beyond simple viral discovery. We could really flesh out what these findings mean for groundwater functioning.

Looking Ahead

Groundwater is not just water. It harbors dense and dynamic communities of bacteria, archaea, and viruses engaged in continuous processes of infection, survival, and evolution. We've opened a window into this hidden world, but there's so much more to discover. Every finding generates new questions. Every question reminds us how much complexity exists in places we've barely begun to explore. The next time you turn on a tap or see a spring bubbling from the ground, remember: there's a whole ecosystem down there. Impacted by forces we are only beginning to understand. And among the most powerful are the tiniest. The viruses that no one can see, but that everyone depends on.

Follow the Topic

-

Nature Communications

An open access, multidisciplinary journal dedicated to publishing high-quality research in all areas of the biological, health, physical, chemical and Earth sciences.

Related Collections

With Collections, you can get published faster and increase your visibility.

Women's Health

Publishing Model: Hybrid

Deadline: Ongoing

Advances in neurodegenerative diseases

Publishing Model: Hybrid

Deadline: Mar 24, 2026

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in