A natural alliance: how plant community changes and microbial responses stabilized peatland carbon in a drying climate

Published in Earth & Environment

Peatlands: Small in area, huge in impact

Peatlands cover just 3% of Earth’s land surface, yet they store over 600 billion tonnes of carbon—more than all the world’s forests combined. These quiet, waterlogged ecosystems are carbon superheroes, capturing atmospheric CO2 and locking it away in deep organic soils for thousands of years. But now, with global warming and more frequent drying, peatlands face a new challenge: ecological transition.

One striking change? The spread of woody plants—shrubs and small trees—into areas once dominated by mosses and grasses. What does this shift mean for carbon storage? How do the hidden microbial players—bacteria and fungi—respond when their plant partners shift? That’s what our team set out to explore.

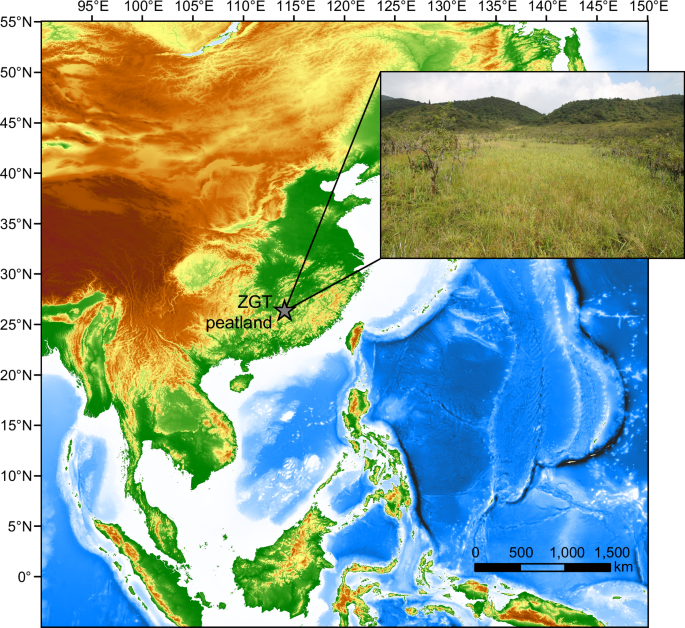

A story from the mountains of southern China

Our research took us deep into the remote Zhaogongting peatland, nestled in the mountains where Hunan meets Jiangxi Province. Each field trip meant hours of hiking narrow forest trails, hauling heavy peat corers and bulky sample bags. Despite the sweat and sore muscles, we were driven by one question: How has this peatland managed to hold onto its carbon through past climate stress?

We focused on a period around 8,000 to 6,000 years ago, when the climate became warmer and drier. Using plant macrofossils, microbial biomarkers, and their isotopic “fingerprints” preserved in peat cores, we uncovered a fascinating ecological dance.

Woody plants step in—and microbes change their tune

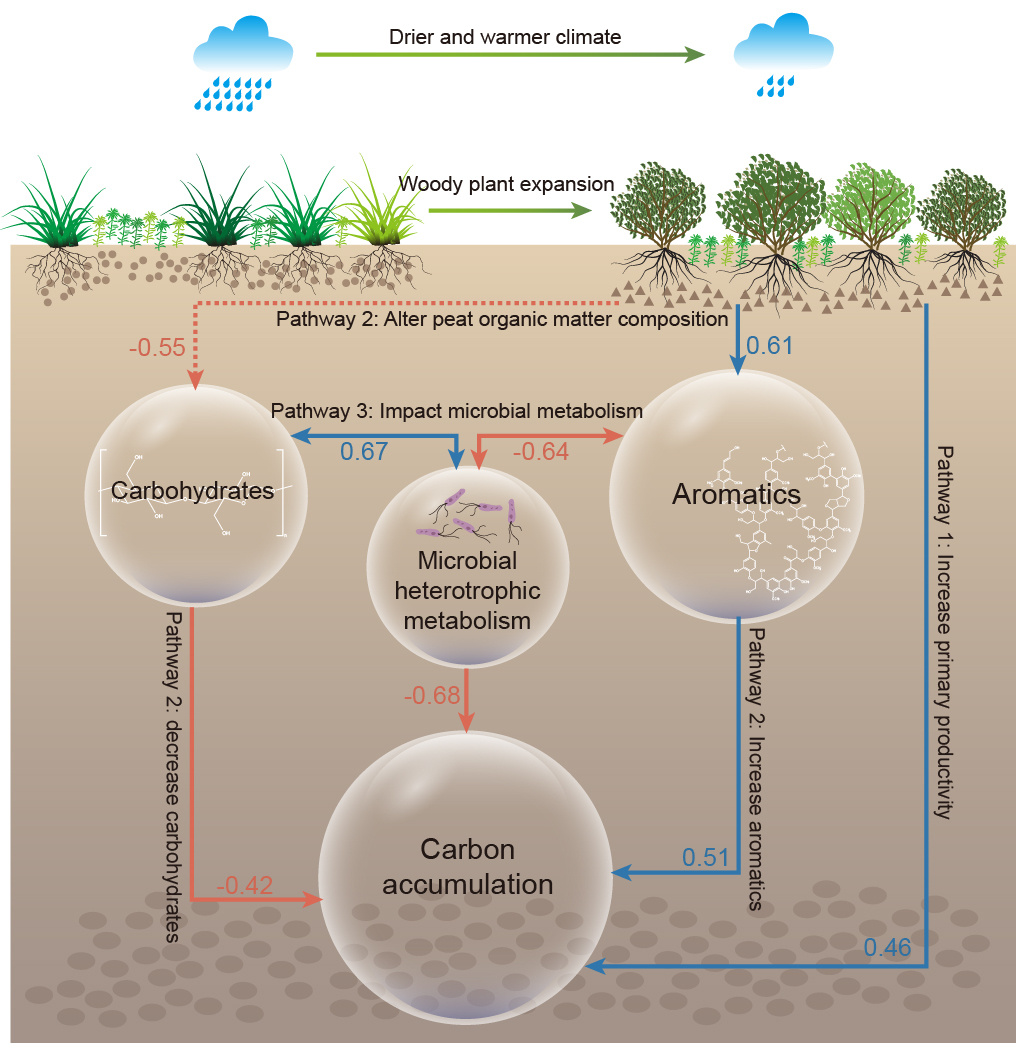

As drying happened from 8,000 to 6,000 years ago, woody plants expanded rapidly, replacing much of the grass-like vegetation. This shift didn’t just change the scenery—it altered the organic composition of the peat, introducing more complex, harder-to-degrade compounds like aromatics. For the microbes living in the peat, this was a game-changer.

We found that bacterial and fungal biomass initially increased during early drying, but soon declined as conditions became more challenging. Microbial heterotrophic activity weakened, likely suppressed by changes in organic matter composition and limited energy sources. In response, microbes have shifted toward more autotrophic or alternative metabolic pathways. This “metabolic switch” helped slow the loss of carbon—an unexpected form of resilience during drying.

A natural alliance: Plants and microbes shield carbon

Surprisingly, during this time of drying and ecological change, the peatland’s carbon accumulation actually peaked—three times higher than in wetter periods. Why? Because woody plants and microbes teamed up, creating a natural defense against carbon loss. During drying, woody plant expansion increased both productivity and the input of more recalcitrant organic matter. But instead of ramping up decomposition to match this carbon influx—as microbes often do under drying conditions—they shifted their metabolism to break down less of it. Together, they built a carbon shield.

Even more exciting, we found similar patterns in peatlands around the world. Our global analysis of over 150 peatland sites revealed that woody plant expansion often boosted carbon storage, especially in the tropics.

Looking forward: When cooperation holds—and when it breaks

As the climate continues to warm, woody plants are once again advancing into peatlands across the globe. In some places, this shift may not spell collapse. Our findings suggest that when plants and microbes work in quiet synchrony—adjusting what enters the soil, and what is broken down—carbon can remain safely stored, even under drying skies.

But resilience is not boundless. Every ecosystem has its threshold, and peatlands are no exception. When drying becomes severe—when the landscape tips from peatland to woodland—the delicate balance may falter. Microbial decomposition could surge, turning these carbon sinks into carbon sources. What was once a shield might become a release.

These are the transitions we now seek to understand. Our international team is tracing them across climates and continents, asking: where does resilience end, and where does risk begin?

For us, every step through wetlands, wilderness, and mountain trails is a step into this question. And with each core, each sample, each quiet hour in the lab, we come a little closer to understanding not only how nature defends its carbon—but how we might help it continue to do so.

Follow the Topic

-

Nature Communications

An open access, multidisciplinary journal dedicated to publishing high-quality research in all areas of the biological, health, physical, chemical and Earth sciences.

Related Collections

With Collections, you can get published faster and increase your visibility.

Women's Health

Publishing Model: Hybrid

Deadline: Ongoing

Advances in neurodegenerative diseases

Publishing Model: Hybrid

Deadline: Mar 24, 2026

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in