How the solar wind slips through Earth’s bow shock

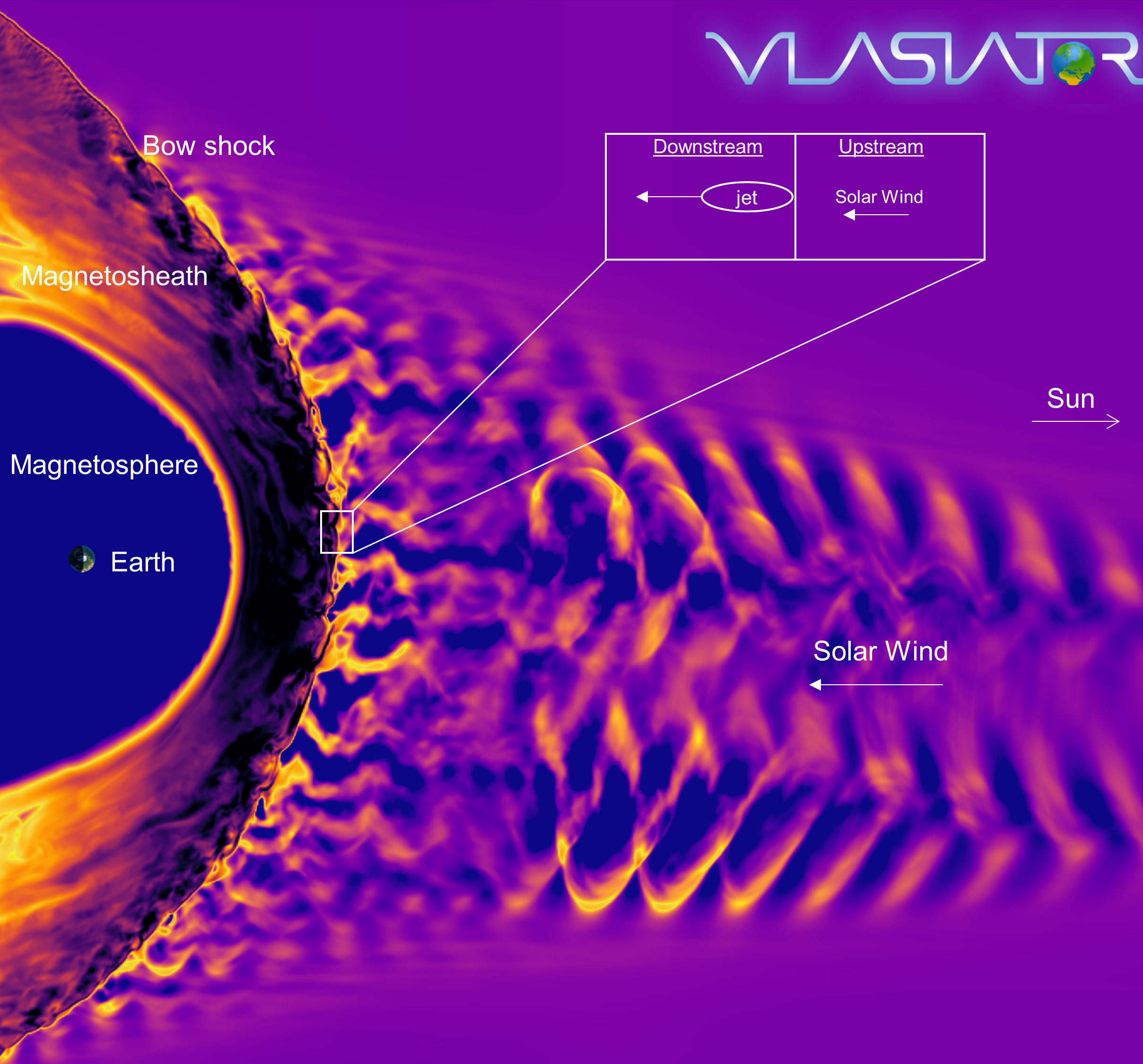

Earth is protected from the potentially harmful solar wind due to its strong magnetic field. As supersonic particles from the Sun are travelling towards us, they meet Earth’s field and form a bow shock. As the solar wind transitions from the bow shock to the magnetosphere, it generates a turbulent and chaotic plasma environment called magnetosheath. That is where the general plasma flow gets braked, thermalized, and compressed while diverging around the Earth.

While this is what typically happens, it is not the full story. Small-scale plasma flows can be found in the magnetosheath, having dynamic pressure much higher than the surrounding plasma and the solar wind. They can have velocities similar to the solar wind values, upstream of the shock, while they can be denser than the downstream magnetosheath. These are the so-called magnetosheath jets. When they reach the magnetosphere, they can have a variety of effects. The most prominent ones include magnetic reconnection, the excitation of plasma waves, or even geomagnetic substorms. However, while jets have been observed for many years, we are still not sure how they manage to form and what allows them to hold such unique properties compare to their surrounding plasma.

Our group’s research on jets focuses on finding out their different types and how they are generated with the use of NASA’s Magnetosphere Multiscale (MMS) mission. After studying jets for quite a few years, we discovered very interesting properties! They appear to be strongly connected to shock dynamics, and they form different classes that correspond to distinct properties and evolution. Recently, we concentrated on finding special cases where the MMS spacecraft provide high-resolution measurements (called burst data) and has an optimal formation of the 4 satellites that could potentially allow us to find how jets are formed (string-of-pearl configuration).

This process brought us numerous measurements which required manual observation and investigation. This was done for several months until I decided to take a break for Easter vacations and visit Greece. While I was commuting from Athens to Thessaloniki by train, I discovered a very peculiar occasion of MMS measurements very close to the bow shock of the Earth.

The satellites were aligned in a special configuration along the sun-earth line and 3 of them were observing mainly the solar wind (upstream) whereas the last one was observing the magnetosheath (downstream). This was intriguing by itself, since typically we hardly get such clear signatures due to the rapid movement of the bow shock and the uncertainty of determining the environment. Looking more and more into these data, I discovered that the closest to the Earth satellite also observed a magnetosheath jet!

After months of analysis, comparison to other events and discussions with my supervisor, and several collaborators, we finally revealed the story behind the jet measurement. It appears that the jet is formed through the evolution of the upstream waves and the reformation of the shock.

One can think of the shock as a constantly reforming surface. The old shock front moves towards the Earth and gets gradually diluted as it forms the magnetosheath, while locally, new waves upstream of the old shock take the lead and act as the local bow shock front. During this process, it appears that part of the solar wind that lies between the new shock front and the old one is effectively transferred downstream of the new shock. This part of the supersonic solar wind has a limited interaction with the old shock front (which now is the magnetosheath region). On the other hand, it has experienced some compression from the evolution of the upstream waves, increasing its density, while its minimal interaction with the shock allows it to retain a relatively high velocity.

These findings provided a direct answer to how we can observe plasma with velocities close to the solar wind downstream of the shock! The described generation mechanism shows that the dynamical evolution of the shock itself (constantly reforming) can allow the formation of jets to take place.

In the future, we want to see whether this type of formation mechanism can be found in other astrophysical and planetary shock environments. Finally, we want to continue our research by performing a comparison with computer simulations and in-situ measurements from other satellite missions.

Poster image Credits : Mary Pat Hrybyk-Keith / NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center.

Follow the Topic

-

Nature Communications

An open access, multidisciplinary journal dedicated to publishing high-quality research in all areas of the biological, health, physical, chemical and Earth sciences.

Ask the Editor – Space Physics, Quantum Physics, Atomic, Molecular and Chemical Physics

Got a question for the editor about Space Physics, Quantum Physics, Atomic, Molecular and Chemical Physics? Ask it here!

Continue reading announcementRelated Collections

With Collections, you can get published faster and increase your visibility.

Women's Health

Publishing Model: Hybrid

Deadline: Ongoing

Advances in neurodegenerative diseases

Publishing Model: Hybrid

Deadline: Mar 24, 2026

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in