How do relativistic electrons form at shocks?

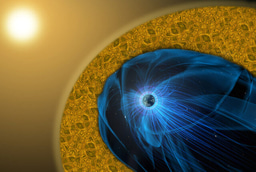

When the fast-moving stream of particles originating from the Sun (Solar wind) encounters Earth's magnetic field, they create a collisionless shock wave known as the bow shock. In Astrophysics, we call these shocks "collisionless" because they form from interaction of charged particles (plasma) with electromagnetic fields, rather than through direct collisions like the shock waves we see forming from supersonic aircrafts at Earth. Similar astrophysical shocks are found across the Universe, in supernovas and in other planetary systems. These shocks act like cosmic trampolines, bouncing particles and boosting their energy with every interaction. After many interactions, electrons gain enough energy to move at nearly the speed of light, becoming highly energetic (relativistic). A substantial portion of the high energy particles observed at Earth, known as "cosmic rays", got their energy from interactions with collisionless shocks.

The Injection Problem

Electron acceleration at shocks requires pre-energization to a specific level, called the injection energy. This is like needing an initial jump to get onto a trampoline. Most electrons in space have too little energy to begin this process. This leaves the following question unanswered: How do the low energy electrons gain the necessary energy to start the bouncing process in order to become part of the observed cosmic ray spectrum? Trying to address this question is known as the "injection problem".

Looking at Nature’s Best Plasma Laboratory

Shortly after moving to the US (around two years ago) to begin working at the Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory (JHU/APL), I started collaborating with my co-authors on a research project using data from NASA’s Magnetospheric Multiscale (MMS) mission. The MMS mission, with its constellation of four uniquely positioned and instrumented spacecraft, offers an exceptional opportunity to study particle energization processes near Earth's bow shock (Figure 1). Earth’s space environment, extensively observed by numerous orbiting satellites, provides an ideal natural laboratory for studying physical processes at collisionless shocks.

A peculiar region upstream of Earth's bow shock is called the foreshock. This region is characterized by highly varying plasma (i.e., particles change direction and scatter all the time), electromagnetic waves, and structures that change over time called foreshock transient structures.

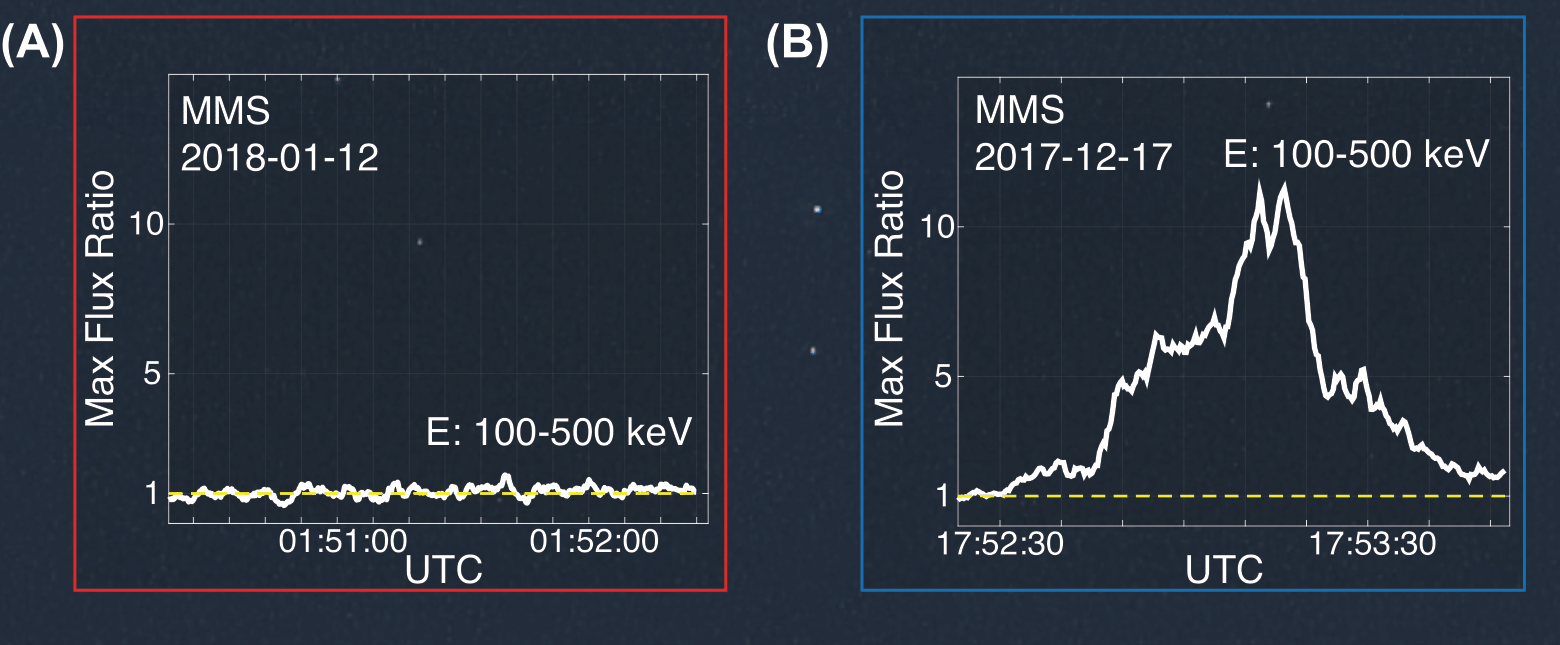

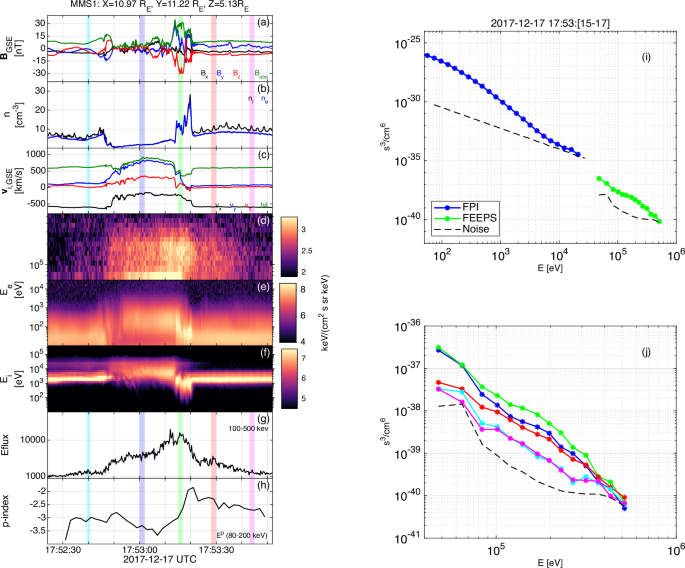

One manifestation of such transient phenomena is an explosive plasma bubble which forms when a sharp change (called a discontinuity) in the magnetic field carried by the solar wind interacts with Earth's bow shock. Interestingly, we observed a curious inconsistency: some bubbles contained highly energetic electrons, while others, with seemingly similar properties, did not (Figure 2).

The Unique Advantage of Foreshock Transients

These plasma bubbles present an ideal environment for electron acceleration. Inside them, the weak and variable magnetic fields allow particles to scatter, interact with electromagnetic waves, and gain energy. Additionally, strong magnetic fields at the bubble edges create localized shocks, further accelerating the electrons. Yet, the key question remained: Why do some bubbles produce energetic electrons while others do not? To dig deeper, we turned to another NASA mission, THEMIS/ARTEMIS, which orbits the Moon. This mission allowed us to study how the solar wind behaves before it reaches Earth and forms these plasma bubbles.

The Role of Fast Solar Wind

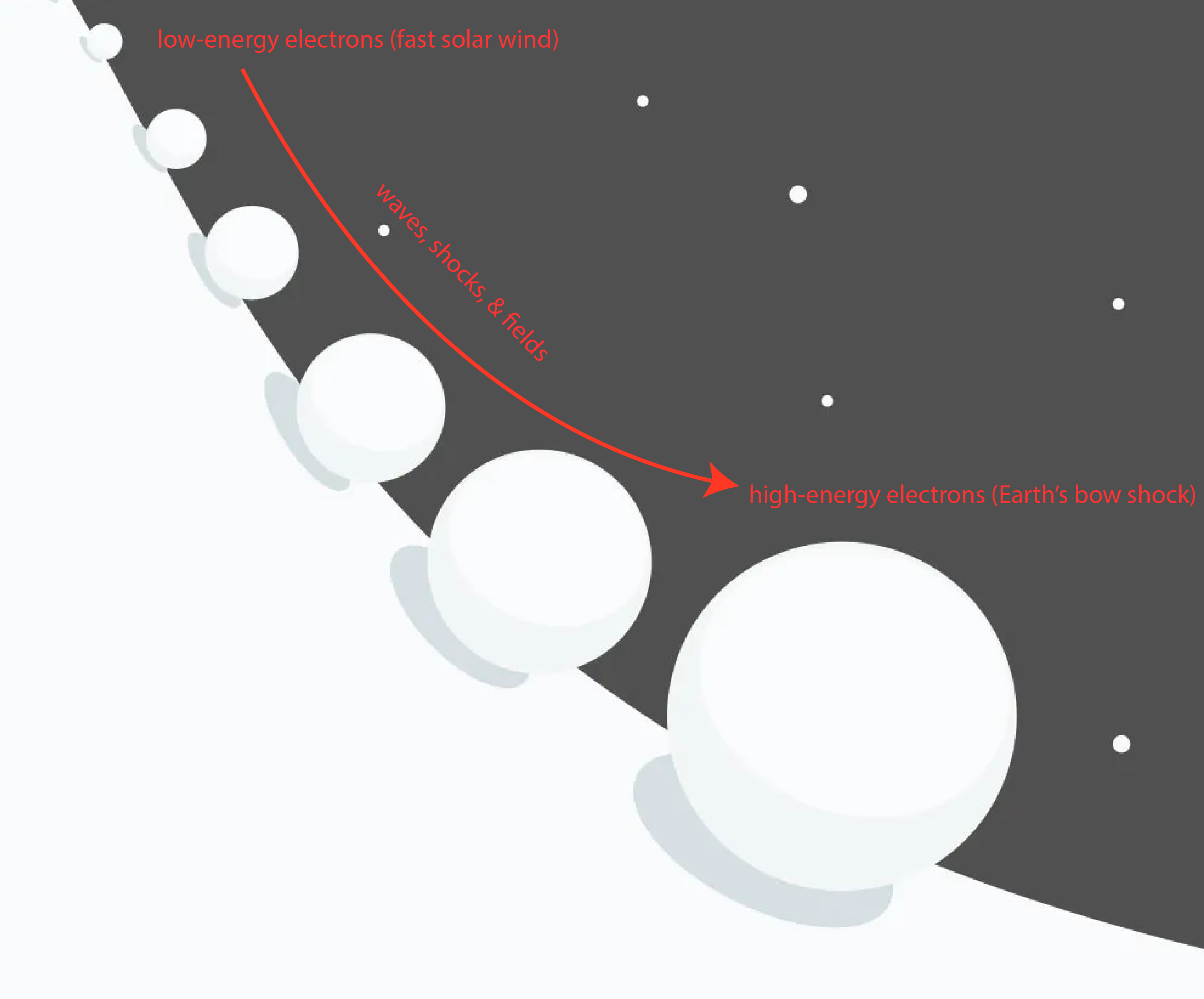

After investigating for many months, and through tens of online meetings with all co-authors, we discovered that a key difference was the speed of the solar wind. Specifically, we found that fast-moving solar wind streams originating from the coronal holes of the Sun were crucial in the energization of electrons. Coronal holes are regions at the poles of the Sun where magnetic fields open outward, allowing particles to escape at high speeds forming what is known as "fast solar wind". These fast streams of particles when arriving at Earth brought with them a "seed" of lower energy electrons, which appeared in all cases where significant energization occurred.

One can think of this seed population as small snowballs rolling down a snowy hill. They start small and slow but form the core needed to grow. As these seed electrons interact with the plasma bubbles, they interact with waves, shocks, and turbulent electromagnetic fields, gaining energy, much like snowballs growing larger as they roll downhill (Figure 3).

Broader Implications

Our work presents a multi-scale process that starts with fast particles from the Sun and ends with relativistic electrons at Earth's bow shock. The physical processes that accelerate the electrons are fundamental and occur throughout the Universe making our model applicable to other planets in our solar system and even to exoplanets around distant stars. In these exotic environments, the unique conditions could allow electrons to reach even higher energies than what we observe near Earth.

By studying our own space environment, we proposed a framework of electron acceleration that addresses the long-lasting and persistent question of "How can energetic (relativistic) electrons form at planetary collisionless shocks?". Apart from addressing this fundamental question, our work also addresses practical concerns related to space weather, as energetic electrons can significantly impact satellite operations, communication systems, and power grids at Earth.

Poster image Credits: ESA/Webb, NASA, CSA, Tom Ray (Dublin)

Follow the Topic

-

Nature Communications

An open access, multidisciplinary journal dedicated to publishing high-quality research in all areas of the biological, health, physical, chemical and Earth sciences.

Ask the Editor – Space Physics, Quantum Physics, Atomic, Molecular and Chemical Physics

Got a question for the editor about Space Physics, Quantum Physics, Atomic, Molecular and Chemical Physics? Ask it here!

Continue reading announcementRelated Collections

With Collections, you can get published faster and increase your visibility.

Women's Health

Publishing Model: Hybrid

Deadline: Ongoing

Advances in neurodegenerative diseases

Publishing Model: Hybrid

Deadline: Mar 24, 2026

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in

Particle motion can only take two forms, one is to move in the particle space in the state of matter, and the other is to propagate in the form of vibrational frequencies.