Is conspiracy mentality in adulthood rooted in teenage loneliness?

Published in Behavioural Sciences & Psychology

Conspiracy theories are a highly contentious topic. In the age of misinformation, we globally face their negative consequences, and these seem to have become even more obvious and widespread in recent years. During the COVID-19 pandemic, it became apparent that conspiracy beliefs can be lethal, as they were linked to vaccine refusal and lower adherence to health guidelines. Likewise, conspiracy theories played a central role in the lead-up to the raid on the U.S. Capitol in 2021, and similar riots in Brazil in 2023.

These events show the vital need to understand why people endorse conspiracy theories. Recent research has identified mistrust, narcissism, and tendencies toward paranoia and schizotypy as some of the important factors. However, most of this research is from after 2020, and to our knowledge, all longitudinal studies on the topic so far have been short-term. This leaves important questions about the emergence of conspiracy beliefs over the lifespan unanswered. Our study helps address this gap by showing that the endorsement of conspiracy mentality might have roots as early as in adolescence.

Loneliness and conspiracy mentality

Several aspects of people’s lives are important for the endorsement of conspiracy beliefs, but researchers have long thought that social frustration and loneliness could stand out. There are three reasons for this. First, conspiracy beliefs may help people make sense of their loneliness (e.g., “I am alone because I understand things that others do not”). In this way, the ego is protected by blaming the outside world. Second, lonely people may lack a social network that could question and correct their budding conspiracy theories. Third, lonely people might seek out any community, including conspiracy groups, that would make them feel that they belong. Conspiracy groups are typically easy to join (e.g., online) and engaging, which makes them an attractive source of social nourishment. At the same time, however, becoming part of such groups may further strengthen people’s conspiracy beliefs.

In our work, we show that both early experiences of loneliness, and the increase of it throughout adulthood, are linked to more conspiracist worldviews in midlife. To do so, we analysed data collected from a large, population-based Norwegian sample followed over 28 years.

Do lonely teens turn into adult conspiracists?

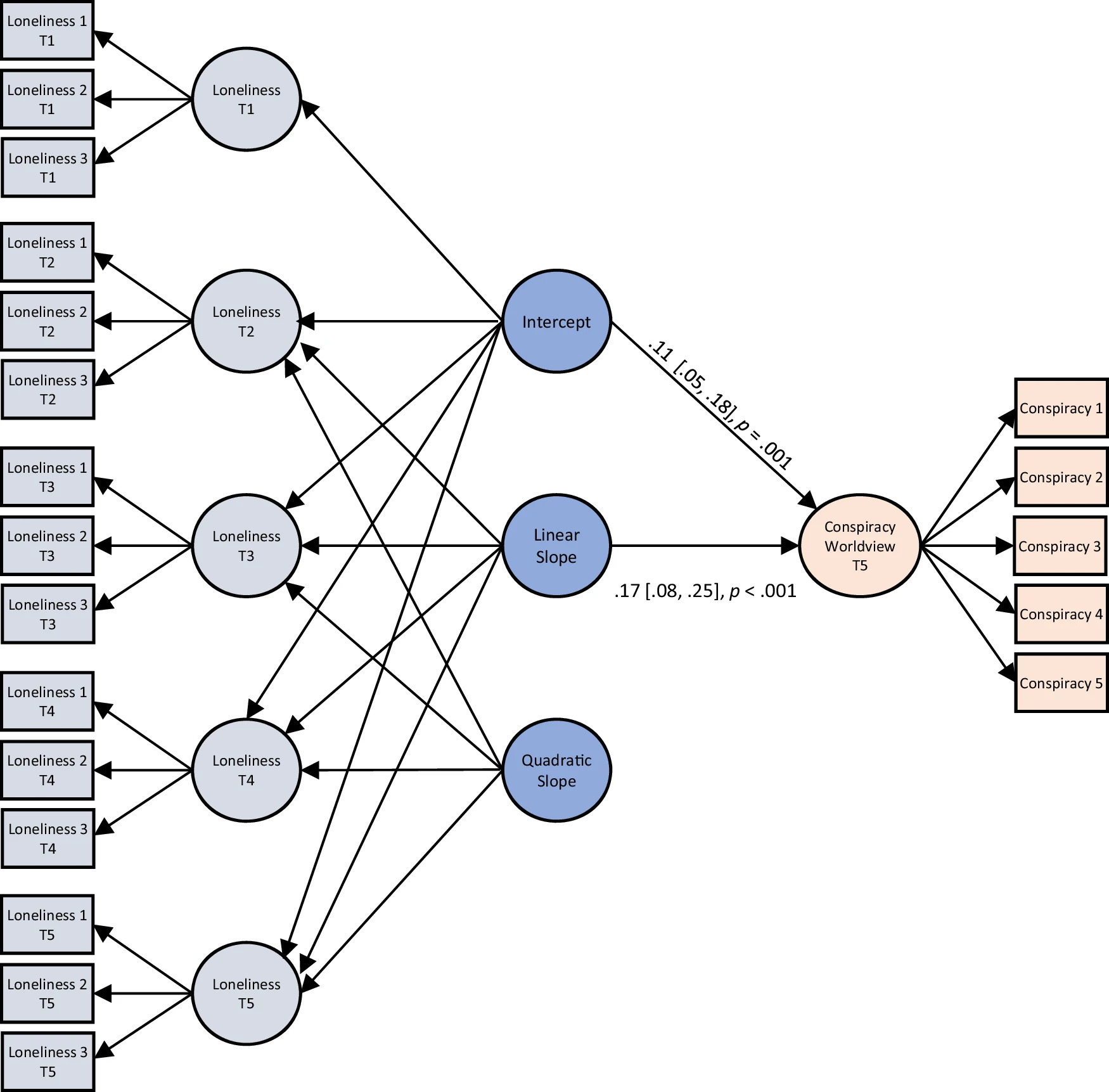

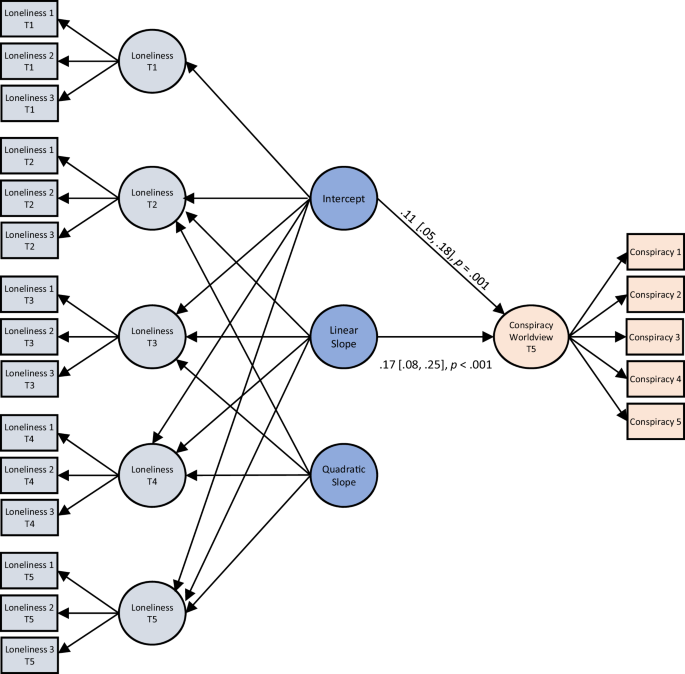

Our research suggests that people who lack social connection as adolescents are more likely to endorse conspiracy mentality as adults. We followed a group of 2,215 research participants from 1992 in their adolescence to 2020 in mid-adulthood. At five times during this period, we measured how lonely the participants felt. When participants had reached mid-adulthood, we also measured the extent to which they held conspiracist worldviews. Data spanning over such a long period of life are relatively unique in social sciences. Our analysis showed that people with high loneliness during adolescence, and those whose loneliness increased over the three following decades, were more likely to hold strong conspiracy beliefs in their mid-forties (see Figure 1). Our results held when controlling for sex, age, parental education, and political orientation in adolescence.

To ensure that these results indeed relate to loneliness and not mental health issues that come with loneliness, we included depression and anxiety in our analyses as control variables. By doing so, we confirmed that the relationships of loneliness in adolescence and loneliness trajectories over 28 years with conspiracy beliefs were not confounded by these factors.

Implications

While it has long been known that loneliness is harmful for psychological well-being and somatic health, we now also understand that loneliness in adolescence and its increase over the lifespan can be linked to people’s likelihood to believe in conspiracy theories as adults.

Critically, loneliness and conspiracy theories potentially create a feedback loop, where individuals experiencing loneliness might engage more deeply with conspiracy theories. These theories, in turn, may lead to further isolation as others may distance themselves from individuals who hold such beliefs. Therefore, it is crucial to identify strategies to break this destructive cycle.

Our intention, however, is not to point fingers at lonely people, but instead to ask how to protect people against the issues that arise with loneliness. Who do we allow to be part of social groups? Who can find a job or a partner? Who obtains a college degree? Inequality of opportunity leads to inequality in belonging and thus affects loneliness. Addressing opportunity inequality by providing equitable access to education, work, and social life may not only reduce loneliness, but may also help to combat the spread of conspiracy beliefs in society.

Follow the Topic

-

Nature Communications

An open access, multidisciplinary journal dedicated to publishing high-quality research in all areas of the biological, health, physical, chemical and Earth sciences.

Related Collections

With Collections, you can get published faster and increase your visibility.

Women's Health

Publishing Model: Hybrid

Deadline: Ongoing

Advances in neurodegenerative diseases

Publishing Model: Hybrid

Deadline: Mar 24, 2026

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in