Mosquito nets - what happens next?

Published in Microbiology, Sustainability, and General & Internal Medicine

When it comes to controlling malaria transmission, insecticide-treated nets (ITNs) are perhaps the most often used tool in sub-Saharan Africa. ITNs are distributed by health agencies during campaigns to control the disease in endemic regions and countries. They do this by blocking mosquitoes biting humans, and they have proven to be effective. But what happens to ITNs at the end of their mosquito-controlling life?

It is estimated that about 2.9 billion ITNs were distributed in malaria endemic countries between 2004 and 2022 – 2.5 billion of them in sub-Saharan Africa. That is a lot of netting to dispose of at the end of their usable life, and could potentially have significant environmental and public health consequences.

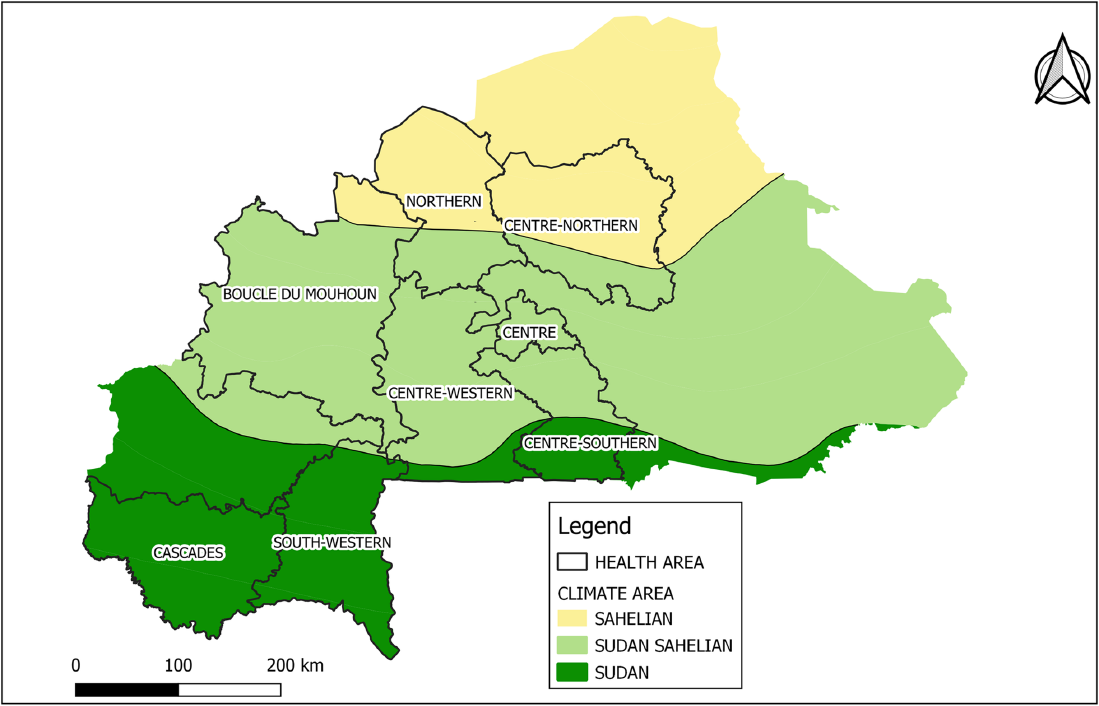

Aristide Hien and colleagues looked specifically at the fate of bednets in Burkino Faso by conducting a quantitative survey of 3780 households across three climatic areas in the country: Sahelian, Sudan-Sahelian and Sudan.

67% of the households were in rural areas, and the average age of participants was 32.5 years. The head of households were predominantly male (between 73 and 85% depending on the climate area they were from), and just over half of the participants had no formal education. For the purposes of their study, Aristide Hien and team defined old ITNs as “a net that has been used for a considerable period and may no longer be effective in providing protection against mosquitoes.”

Of all the surveyed households, 87.4% disposed of their ITNs once they were no longer effective in providing protection against mosquitoes, but worryingly 12.6% of households still used old ITNs as mosquito nets. The study team defined disposal as: “the methods and practices used to manage insecticide-treated nets that are no longer useful for their intended purpose, such as preventing mosquito bites.” So they do not necessarily mean ‘thrown away’. In fact, of those that ‘disposed’ of their ITNs, the vast majority of the ITNs were either thrown in the garbage OR an alternative use was found for them. A very small proportion of nets were buried in the ground or burned, and there was a small proportion whose disposal method did not fit one of the defined modes of disposal listed by the study team and were termed ‘other uses’.

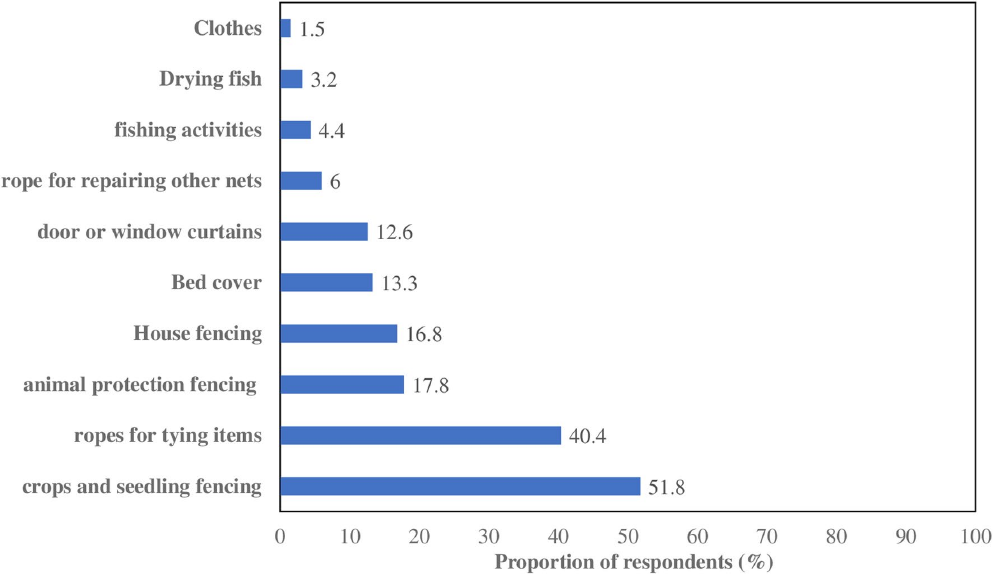

The Alternative uses of nets showed the ingenuity of people surveyed, and they clearly see the value of nets beyond their intended ‘usability’ (to stop mosquitoes biting). The graph below, taken from Aristide Hien and colleagues’ paper, shows the many uses that fall under the term ‘Alternative uses’ . For example nets were used in fencing for crops and seedlings; ropes for tying items such as pots and pans together; animal protection fencing; house fencing; bed covers; fishing and dry fishing; covering pots and pans; and curtains for doors or windows.

Across the three climatic areas covered in the household surveys, there were variations in the disposal methods, for example in the Sudan climatic zone, the vast majority of respondents would bury or burn their nets as opposed to throwing them in the garbage. There were also variations in the alternative uses of nets. For instance those households in the Sahelian climate zone were more likely to use the old nets for fishing, whilst in the Sudan-Sahelian zone would mainly use them as bed covers and those in the Sudan zone would use the nets as ropes for tying or as house fencing.

Reading the paper, I found the direct quoted statements from the participants much more insightful in understanding why and how the nets are used in different ways than just solely looking at the numbers:

“Most people sell their old ITNs to wood sellers, gardeners, or livestock farmers”

“Women repurpose old mosquito nets to tidy up their homes by using them to tie up their own items such as crockery and clothes”

Here, people tie them up to keep hay for the animals”

“Old ITNs are used by motorbike taxis to cover cabbages during transport”

“They also use the nets to cover food and vegetables when transporting them to sell at the market”

“People in our community use these old ITNs to cover their granaries”

“We use these old nets to wash our dishes and ourselves. Sometimes, during the rainy season, the children use them to catch small fish and bring them back for us to cook”

And one of the ‘other' uses for nets was rather macabre, but shows really the extent to how useful nets can be ( beyond their intended purpose of reducing malaria transmission, of course):

“We use these old mosquito nets to cover corpses”.

Aristide Hien and colleagues conclude that there are diverse uses of old nets. The study highlights the need for strategies and guidelines to manage the safe disposal or repurposing of ITNs. This could help improve the environmental and public impact of old nets.

Follow the Topic

-

Malaria Journal

This journal is aimed at the scientific community interested in malaria in its broadest sense.

-

BugBitten

A blog for the parasitology and vector biology community.

What are SDG Topics?

An introduction to Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) Topics and their role in highlighting sustainable development research.

Continue reading announcementRelated Collections

With Collections, you can get published faster and increase your visibility.

Elimination of infectious diseases of poverty as a key contribution to achieving the SDGs

Publishing Model: Open Access

Deadline: Ongoing

AI for Malaria Elimination: Data-Driven Innovations in Surveillance and Control

As malaria-endemic regions continue to generate vast and complex datasets—from epidemiological surveillance and vector control to genomic sequencing and intervention outcomes—the need for robust, scalable, and intelligent data management systems has never been more urgent. This collection explores the transformative impact of Artificial Intelligence (AI) on managing, integrating, and interpreting malaria-related data to support research, policy, and public health action.

While AI applications in diagnostics have received considerable attention, this collection shifts the focus to underexplored areas such as:

-Data harmonization and integration across varied sources (e.g., clinical, entomological, environmental, genomic, geospatial, intervention efficacy studies, socioeconomic, and surveillance

-Predictive modeling and decision support systems for malaria control and elimination strategies

-AI-driven tools for real-time surveillance, outbreak detection, and resource allocation

-Ethical, governance, and equity considerations in the deployment of AI for malaria data management

-Infrastructure and capacity-building for sustainable AI adoption in low-resource settings

We welcome original research, case studies, reviews, and methodological papers that demonstrate innovative uses of AI to enhance the quality, accessibility, and utility of malaria data. Contributions that address challenges in data interoperability, bias mitigation, and community engagement are especially encouraged.

This collection aims to foster interdisciplinary dialogue and highlight scalable solutions that can accelerate progress toward malaria elimination through more innovative data practices.

This Collection supports and amplifies research related to SDG 3, Good Health and Well-Being.

All submissions in this collection undergo the journal’s standard peer review process. As an open access publication, this journal levies an article processing fee (details here). We recognize that many key stakeholders may not have access to such resources and are committed to supporting participation in this issue wherever resources are a barrier. For more information about what support may be available, please visit OA funding and support, or email OAfundingpolicy@springernature.com or the Editor-in-Chief.

Publishing Model: Open Access

Deadline: Aug 11, 2026

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in