Paradox Lost

Published in Ecology & Evolution, Zoology & Veterinary Science, and Anatomy & Physiology

I feel

The link of nature draw me: flesh of flesh,

Bone of my bone thou art, and from thy state

Mine never shall be parted

― John Milton, Paradise Lost

A Japanese expression for being fired at job literally translates to “being decapitated”. Though hair-raising, the origin for this expression has little to do with the death penalty. Rather, it is rooted in a traditional puppet theatre where masters take the heads off puppets after each show. With this background I harbour quite different –– and likely unintended by the artist –– kinds of impression for Gustave Moreau’s vision of Salome in L’Apparition or that of Orpheus’s death. But this much is clear. No matter what cultures we grow up in, we all attach special psychological importance to the integrity of the head-trunk connection in the way we do not for other anatomical junctions (we would feel deeply unsettled if all that’s left of the Nefertiti Bust were just her head; yet we pose for selfies with Venus de Milo). And this is for good reason.

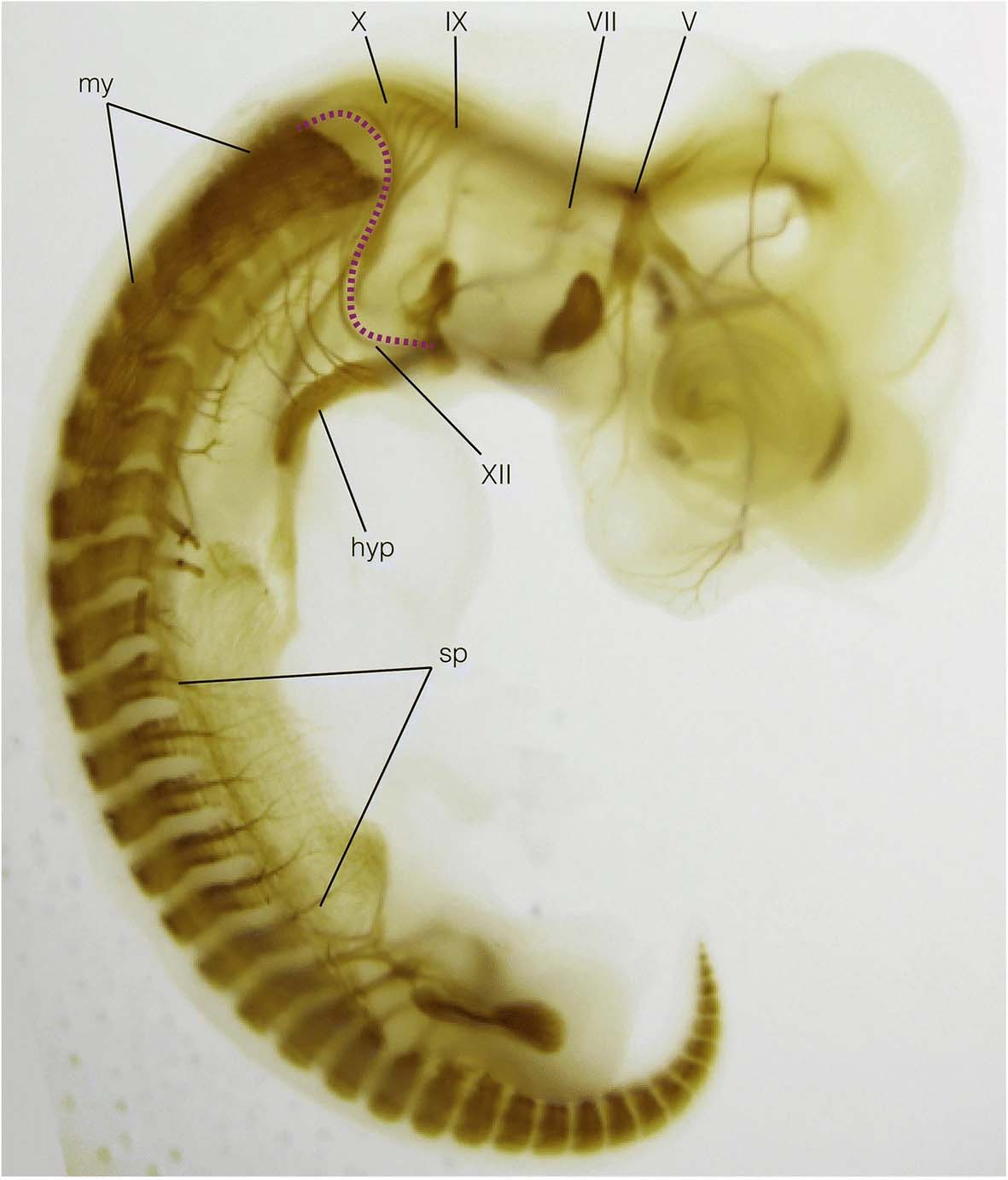

Our head is attached to the torso in a very complex fashion. The neck and throat bridge these two regions; the shoulders provide an anchoring point for these muscular connections (a cantilever of the ‘bridge’); the heart is enclosed by the girdles; connected to it, arteries and veins crisscross like the underground canals of Paris; one cranial nerve (vagus) follows the esophagus and reaches out to the heart like the thread pulled out from Adriane’s hand; trunk nerves loop and bundle like the cords of your AV system to supply the neck and throat musculature and arms. Developmentally, the trunk begins along the body axis with a notochord, paraxially behind the otic capsule in a series of somites, and viscerally behind the pharyngeal arches with lateral plate and peritoneum. Many cell lineages (notably neural crest- and mesoderm-derived ones) migrate, proliferate, and differentiate across and along this S-shaped interface.

If cyclostomes (the lineage of living jawless fishes including hagfishes and lampreys) ever evolved intelligence enough to appreciate Moreau, I doubt they’d share such capital sentiments with us. Their head is attached to the trunk differently, with unique extension of trunk muscles to wrap around the face. How to connect the head with the trunk is thus one major theme of early vertebrate evolution, destined so by the very origin of our lineage as chordates with a clear head-trunk differentiation built in the body plan.

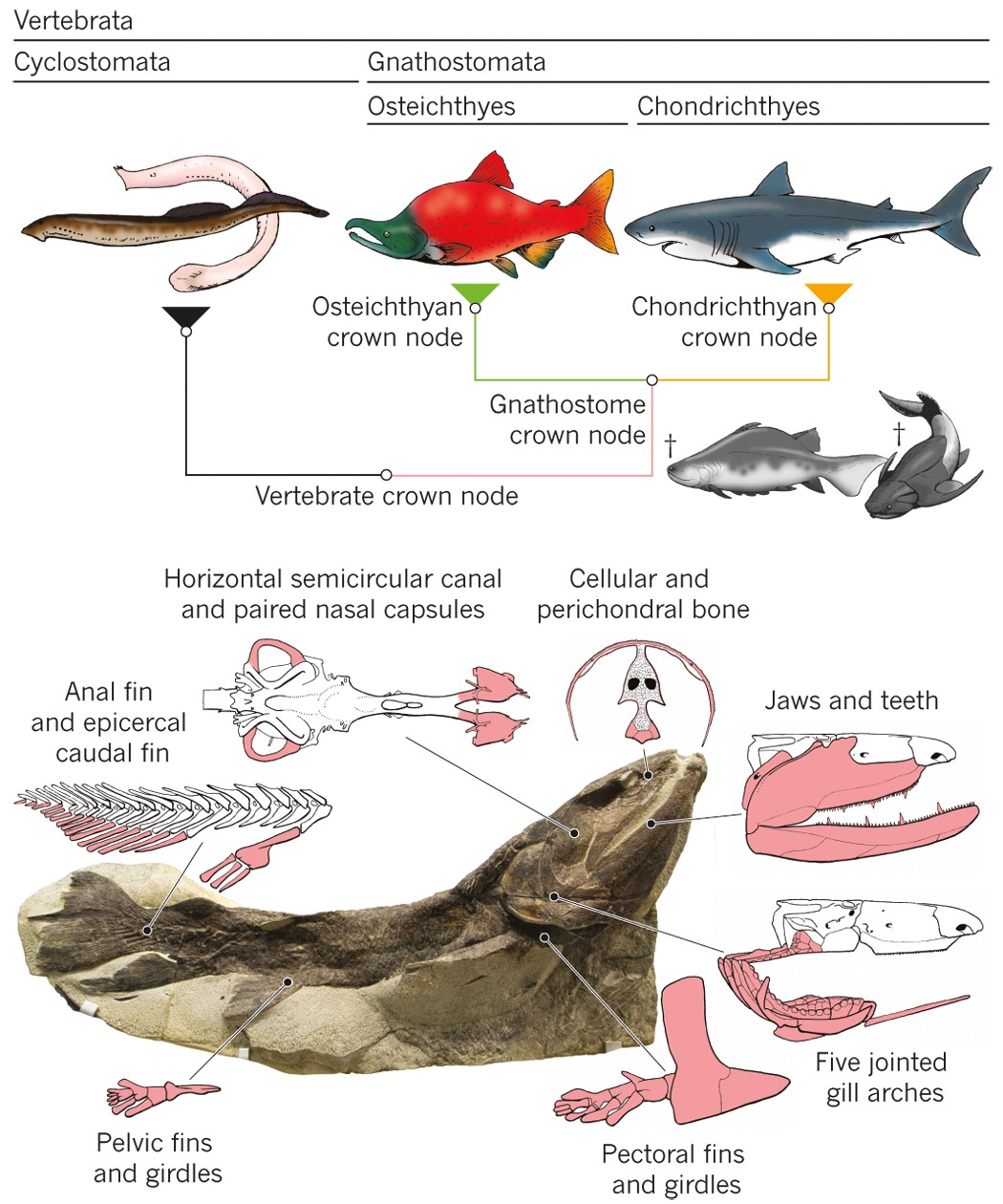

The question is how the head-trunk interface was reconfigured at the cusp of explosive radiation of early jawed vertebrates. This radiation gave rise to the lineages that now account for 99.8% of all living vertebrate species. The (then) new bunch of fishes featured not just jaws, but also some key elements of the modern vertebrate 'body plan' from the number of nostrils to paired appendages.

Classically, paleontologists turn for such questions to osteostracans, the last lineage of jawless vertebrates to diverge. Conveniently, osteostracans form a film of bone on the surface of cartilage so what otherwise decays as soft tissue in most jawless vertebrates can be preserved in fossils. The literature is thick on the osteostracan internal anatomy reconstructed from these perichondral bone films, beginning with Erik Stensiö’s classic monographs and culminating in Philippe Janvier’s masterpieces in the 1980’s. These giants of the field made serial grinding sections of the fossils and crafted models with wax cutouts –– this is manual tomography before CT scanning techniques became the state of the art. These models are described and illustrated so lucidly that few felt compelled to apply CT scans to repeat what we seem to already understand in detail. Based on these earlier contributions, osteostracan internal anatomy has been interpreted as rather primitive, somewhat like that of lampreys. Meanwhile, galeaspids –– another lineage of jawless vertebrates –– were shown to have jawed vertebrate-like nasal anatomy, setting seemingly primitive but phylogenetically more derived osteostracans in an awkward position.

To resolve this paradox, the time has finally come to shed light (in this case high-energy X-ray beam) on osteostracans. With Philippe Janvier on our team, we set our focus upon Norselaspis glacialis, a small osteostracan from the Eary Devonian of Svalbard, to make a full circle on the species Philippe described in his monograph. Pierre Gueriau identified a new specimen out of the 1969 collection of sandstone nodules at the Museum national d’Histoire naturelle. The specimen was brought to the synchrotron scanning facility of Swiss Light Source with the technical help of Felisa Berenguer, Federica Marone, and Sebastian Schöder. The scan data were meticulously segmented by Kristen Tietjen over the years straddling the COVID pandemic, advised between Michael Coates and myself.

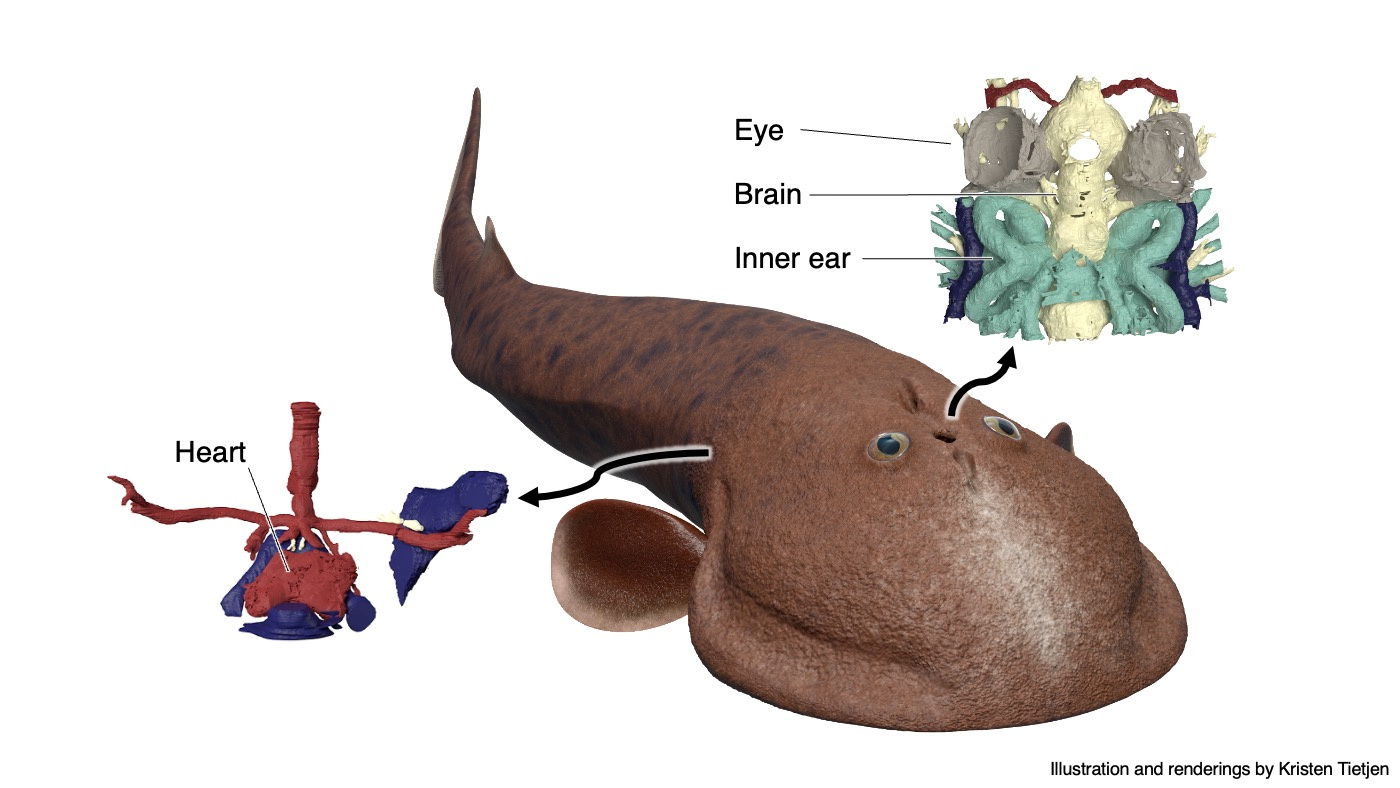

The result is stunning. Although the reconstructed anatomy mostly upheld the original work by Philippe Janvier, we made sweeping updates to its interpretation. Norselaspis turned out to be surprisingly jawed-vertebrate-like and anatomically not as primitive as previously thought. Our interpretation changed so drastically because with sub-µm resolution of synchrotron scanning allowed us to differentiate taphonomic artifacts from skeletal morphology, which was beyond the power of serial optical observations on manually ground sections.

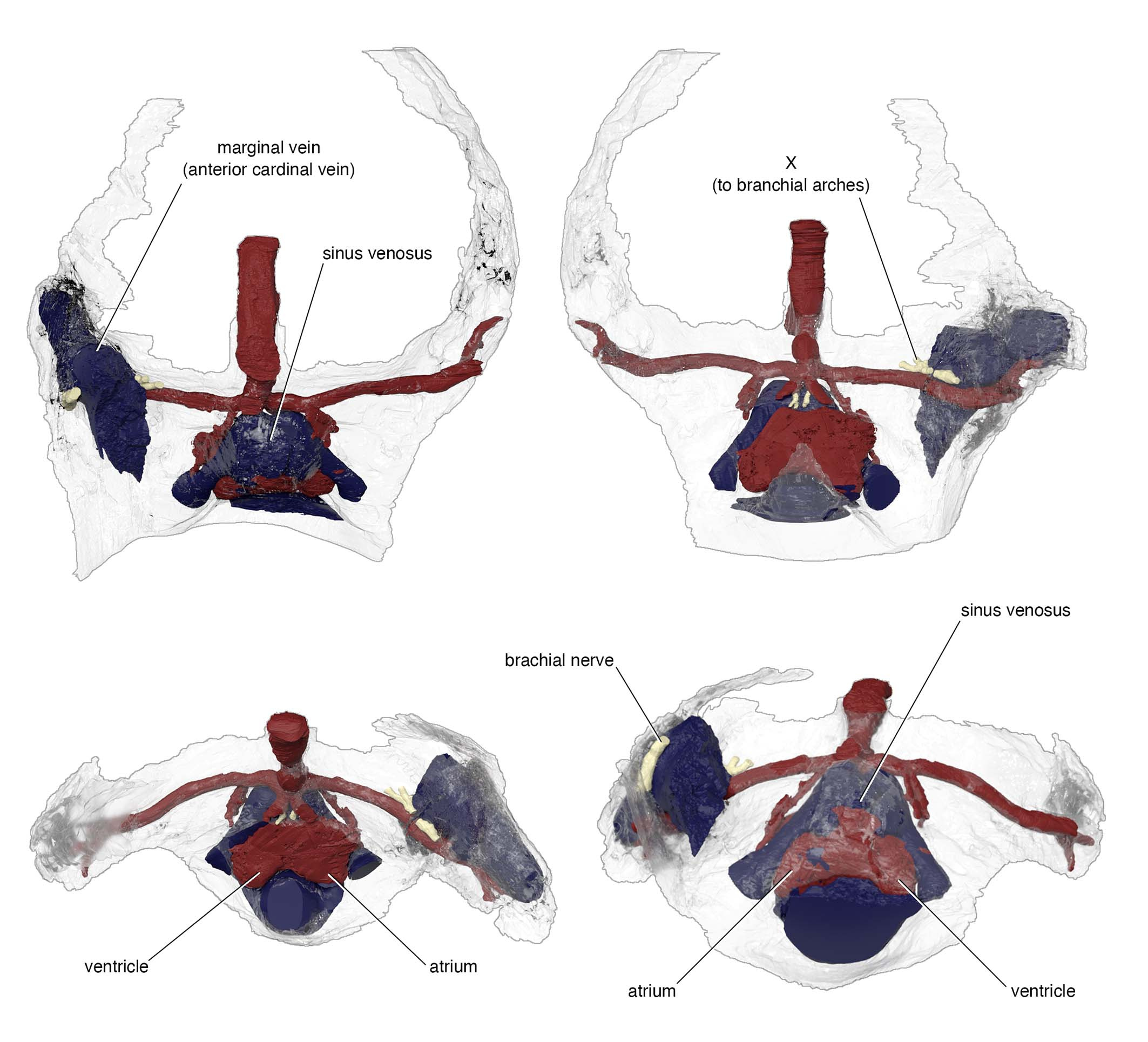

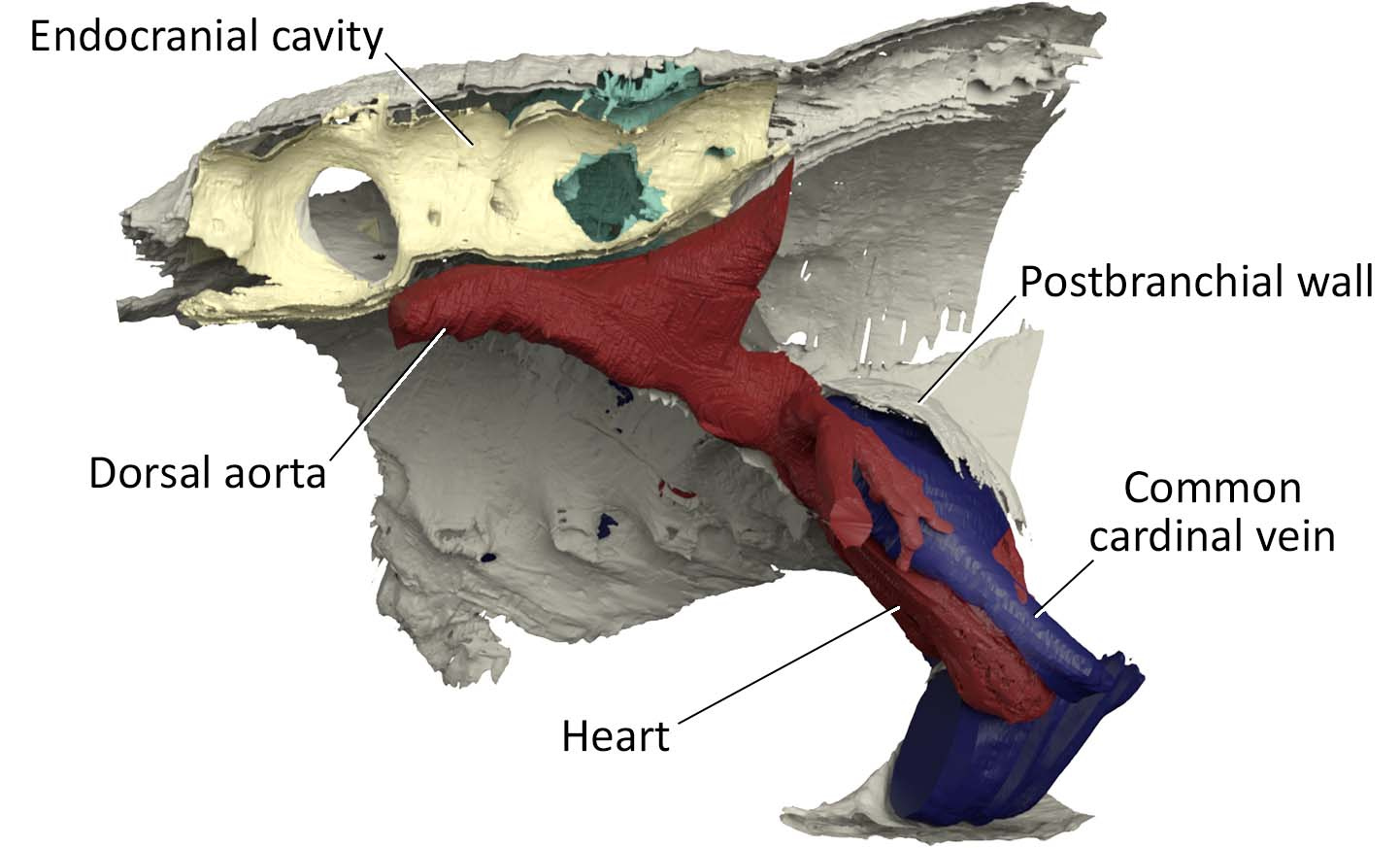

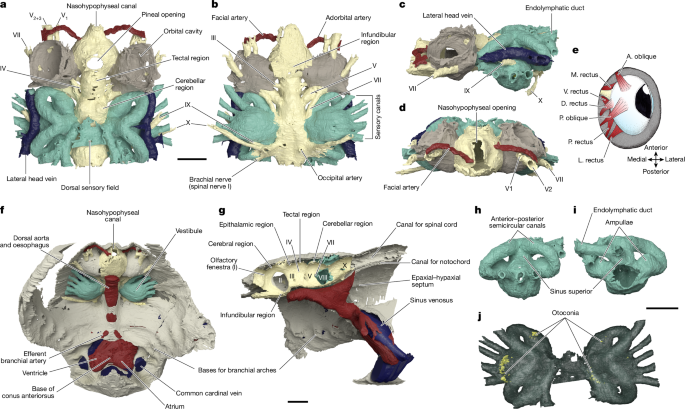

(Above) Visual summary of reconstructed internal anatomy of Norselaspis glacialis. Rendering and movie prepared by Kristen Tietjen.

One example is the chamber that housed a heart. In the specimen used for the original reconstruction in 1981, its bony ceiling had a window, and it was interpreted that the single cardinal vein drained blood through it like in lamprey. Our scan of the new specimen revealed that this window was damage in the previous specimen, and the roof of the pericardium was completely closed. Instead, our new reconstruction showed that cardinal veins are paired between either side of the heart, draining greater volume of blood than in lamprey up to a large sinus sitting atop the heart. This drainage system is much like that of a jawed vertebrate. To describe it cheekily, I might even say that Norselaspis has a shark’s heart under lamprey’s skin.

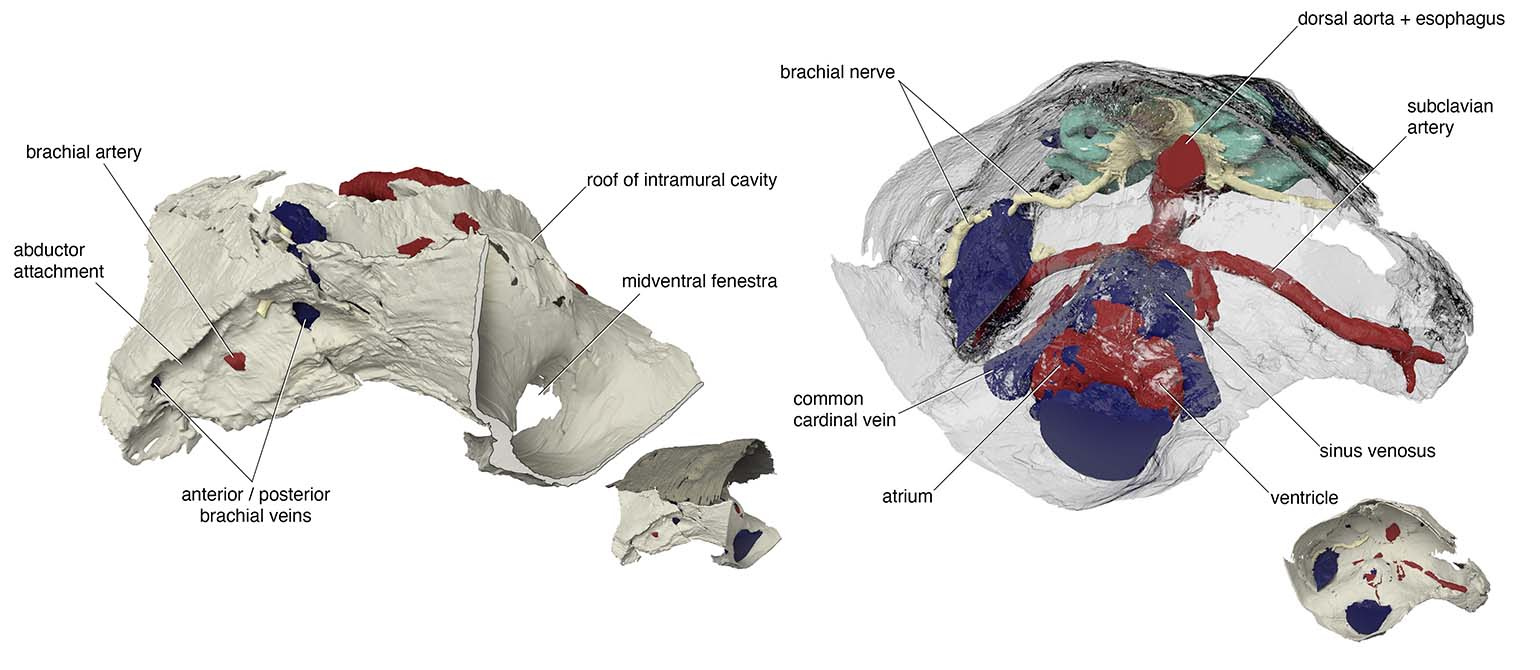

Another example is in the attachment area for pectoral fins. There was a region of unfinished bone in the previous specimen of Norselaspis, which was interpreted to have been capped by an articular cartilage. Implication: osteostracans had a synovial joint. It has been cited as key evidence for the deeper origin of skeletal joints in vertebrates before jaws. Our scan of the new specimen showed that this, too, was a damage to the original specimen. Implication: synovial joints evolved in jawed vertebrates, presumably at the mandibular hinge and/or between segments of the branchial arches*. In Norselaspis, the pectoral fins had a fleshy base, and they were tilted in angles off horizontal plane, suggesting their role in controlling drag rather than being a simple lift surface.

*However, this does not mean that jawless vertebrates entirely lacked skeletal joints –– these joint-like structures, with a possible link to the origin of synovial joints, have been discussed previously by Philippe Janvier (1981, 1985a, b, 1995), Zerina Johanson (2009), and Tetsuto Miyashita (2016).

Renderings by Kristen Tietjen.

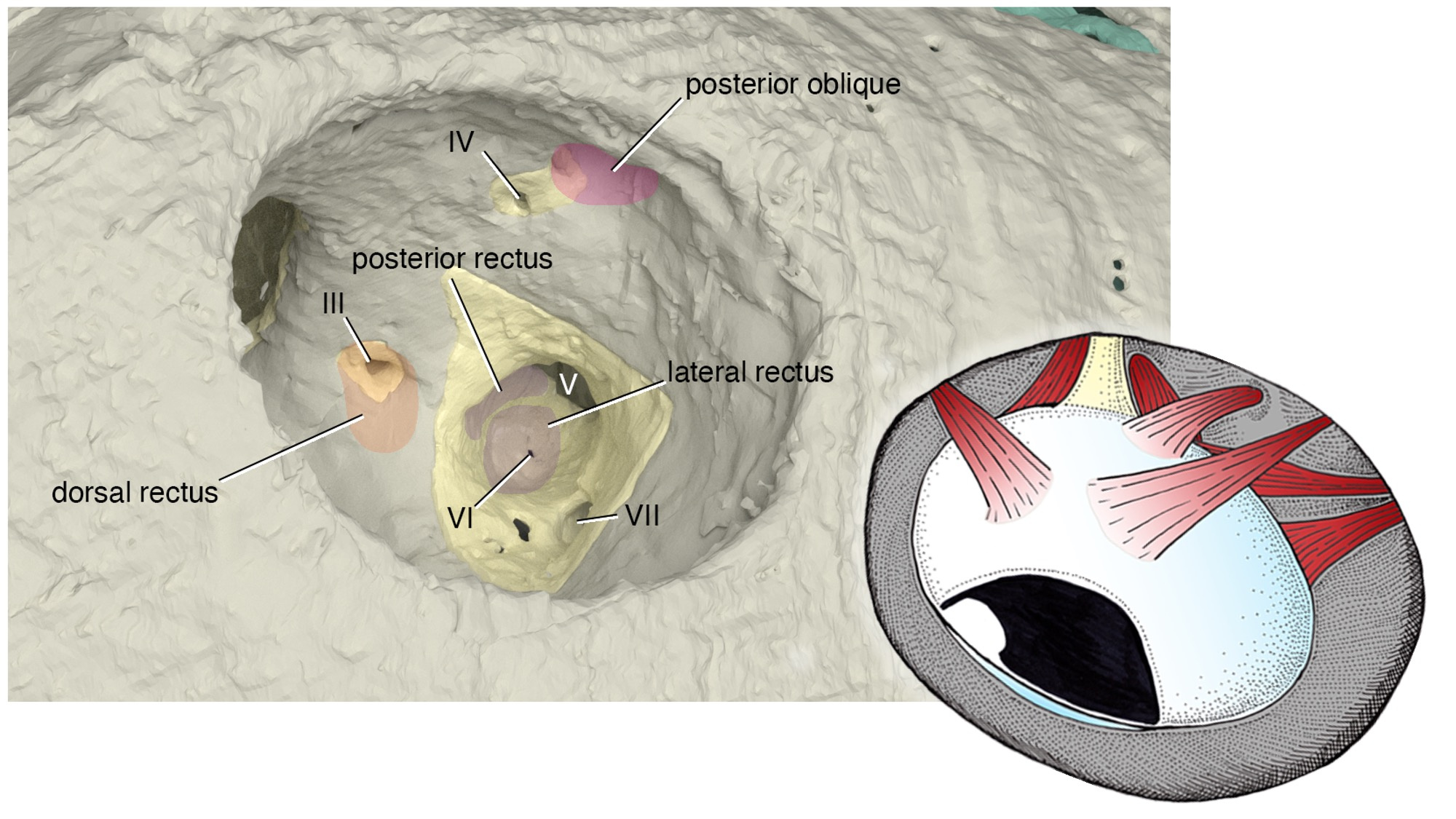

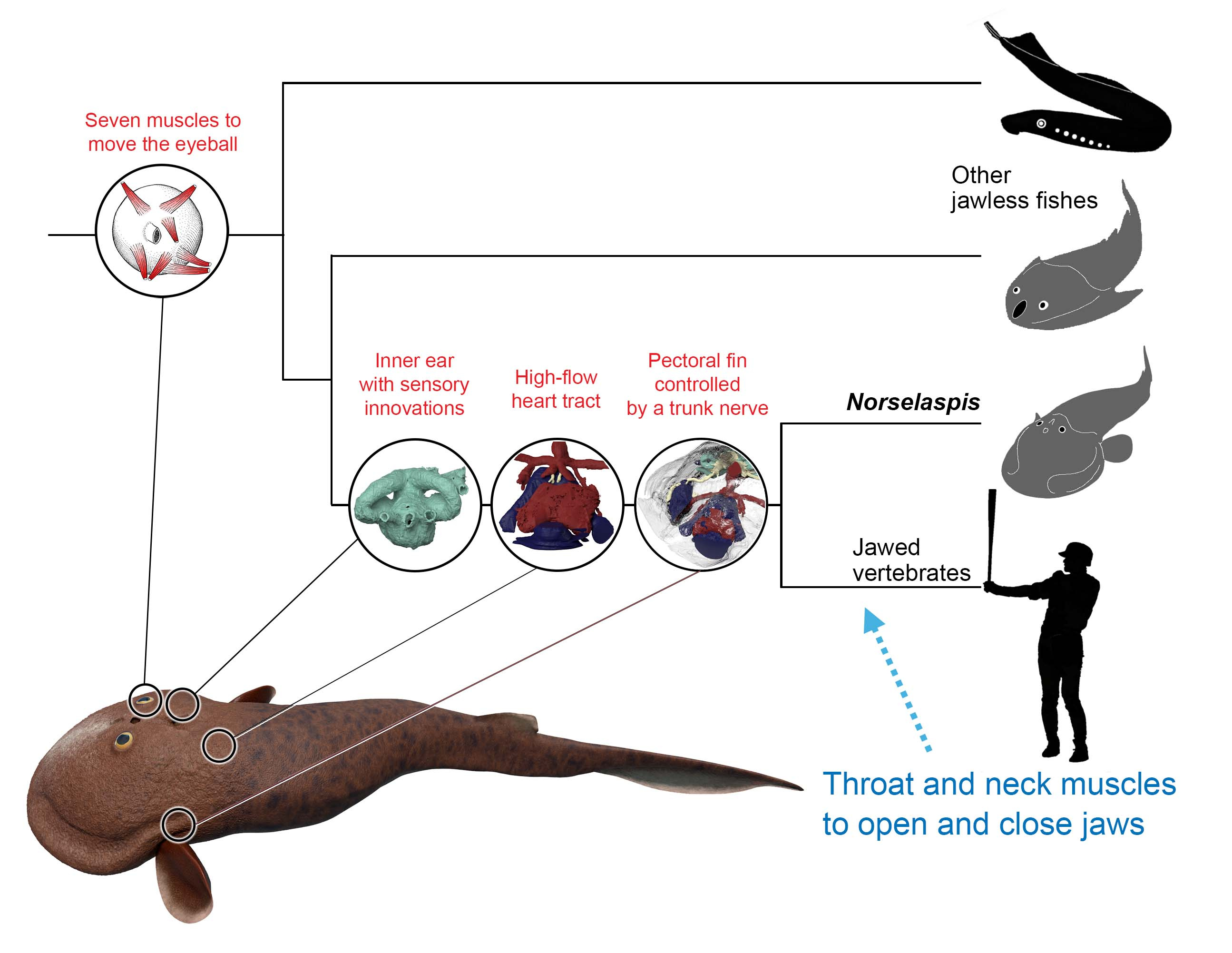

What is truly remarkable about the new reconstruction is its breathtaking resolution. The orbit of Norselaspis is only about 2 mm wide, but even at this scale we identified scars in the bone left by the attachment of extrinsic eye muscles. Nearly all vertebrates have a set of six extrinsic eye muscles, but Norselaspis has seven, as do primitive jawed vertebrates. This discontinuity generates a new hypothesis that vertebrates ancestrally had seven eye muscles, but lampreys and jawed vertebrates each lost one muscle. These muscles are generally considered an anatomical constant, but here the fossil record reveals their dynamic evolutionary history.

Note: The orbit is barely 2 mm across!

Rendering of the orbit by Kristen Tietjen. Anatomical drawing by Tetsuto Miyashita.

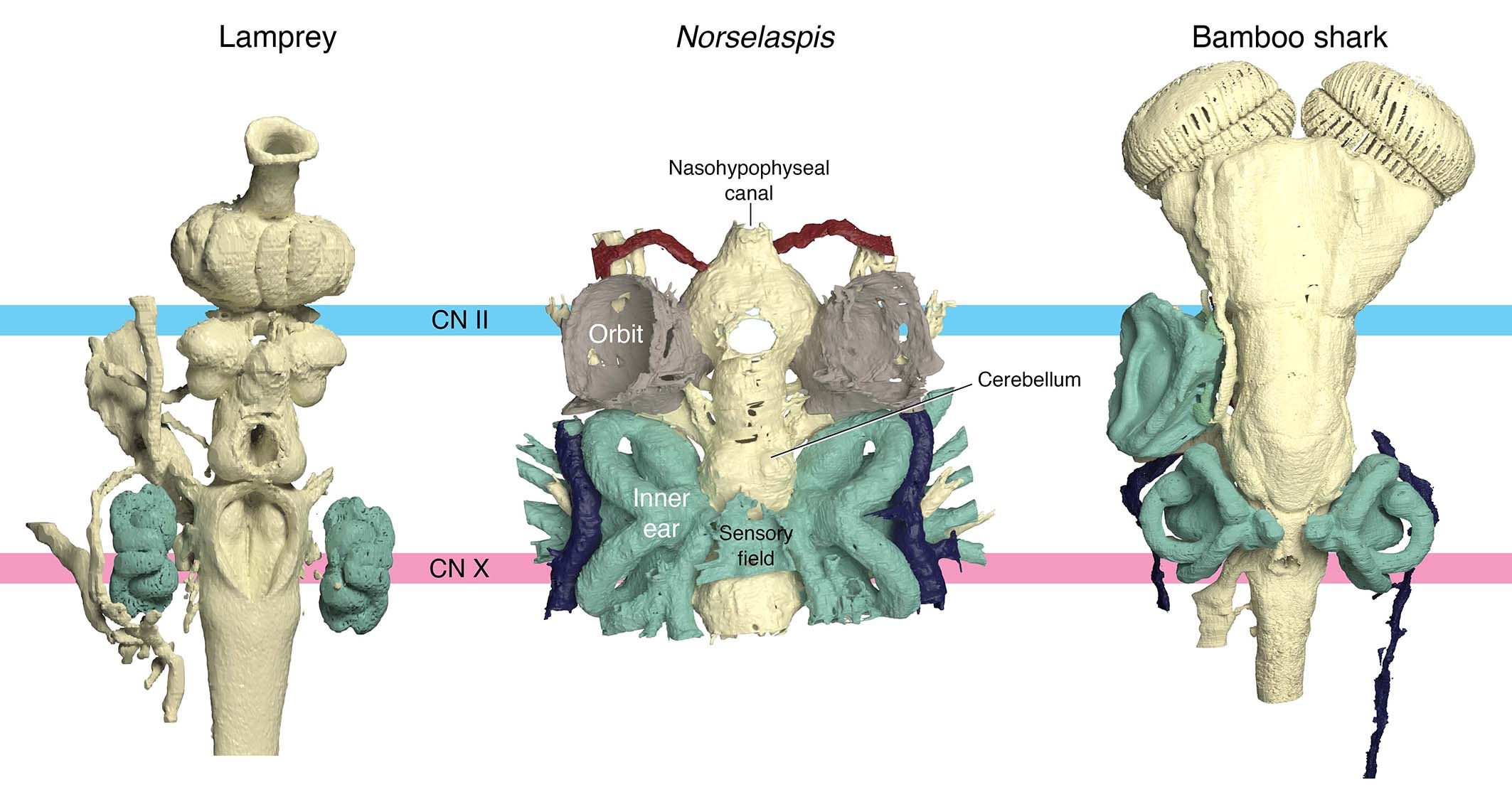

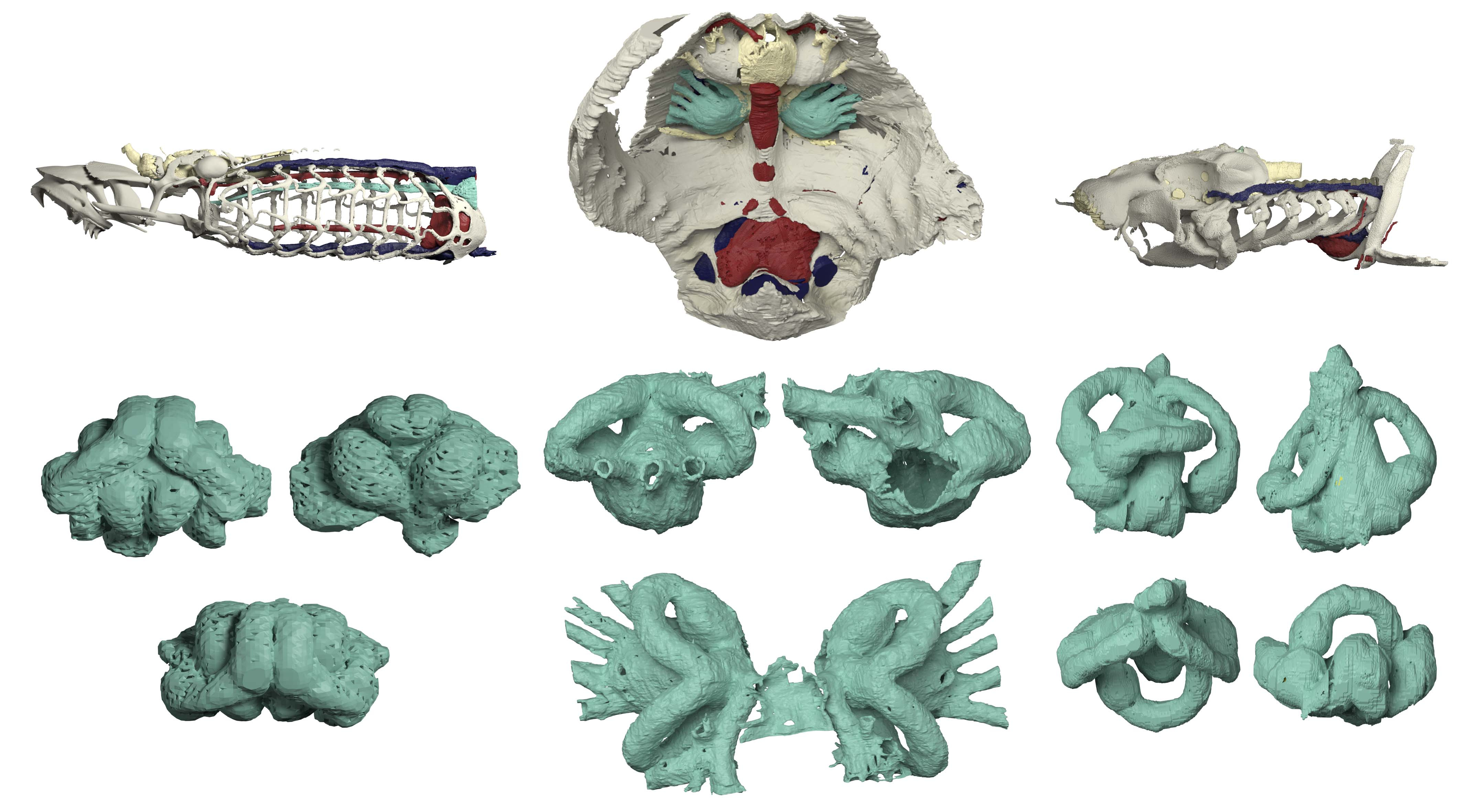

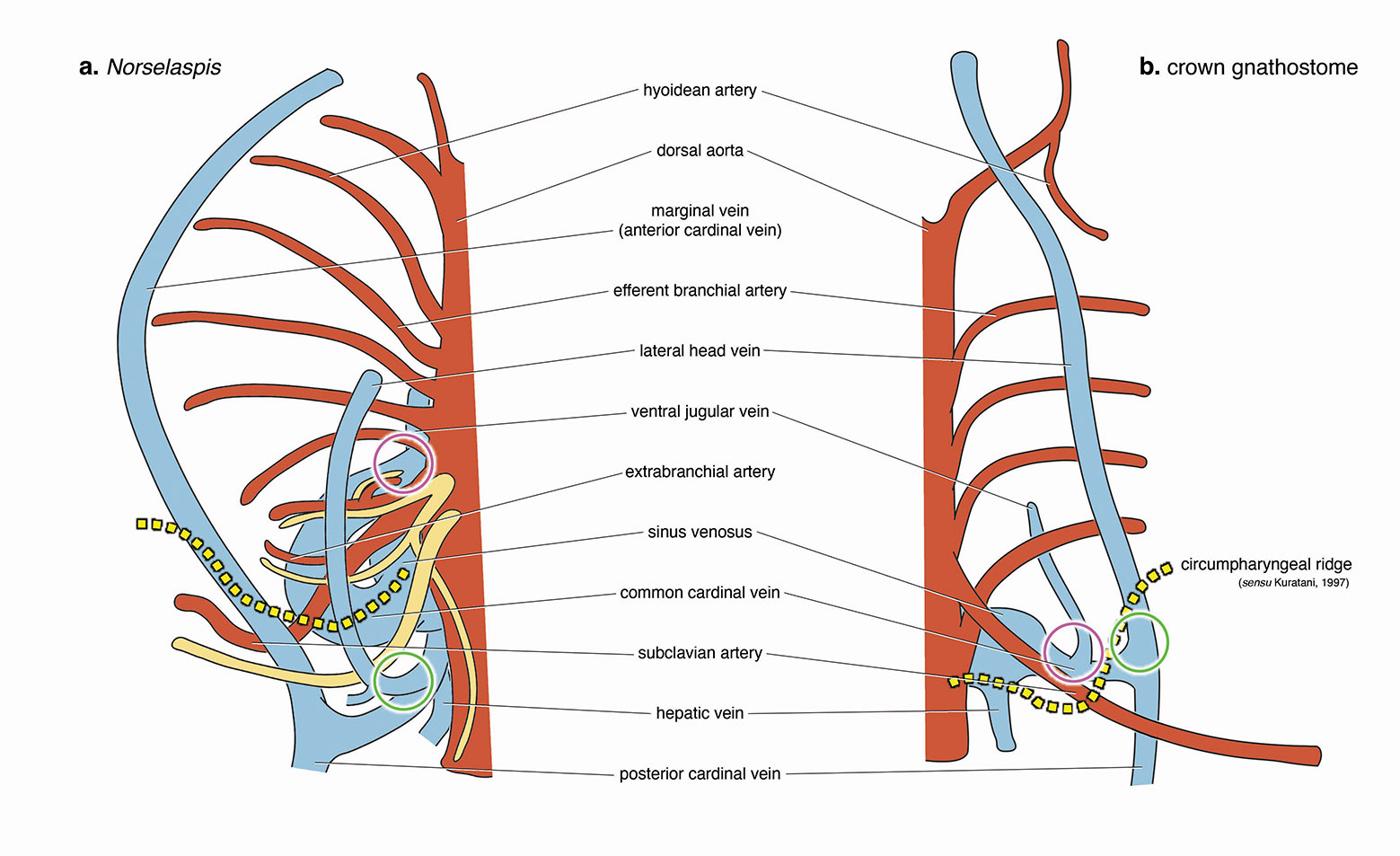

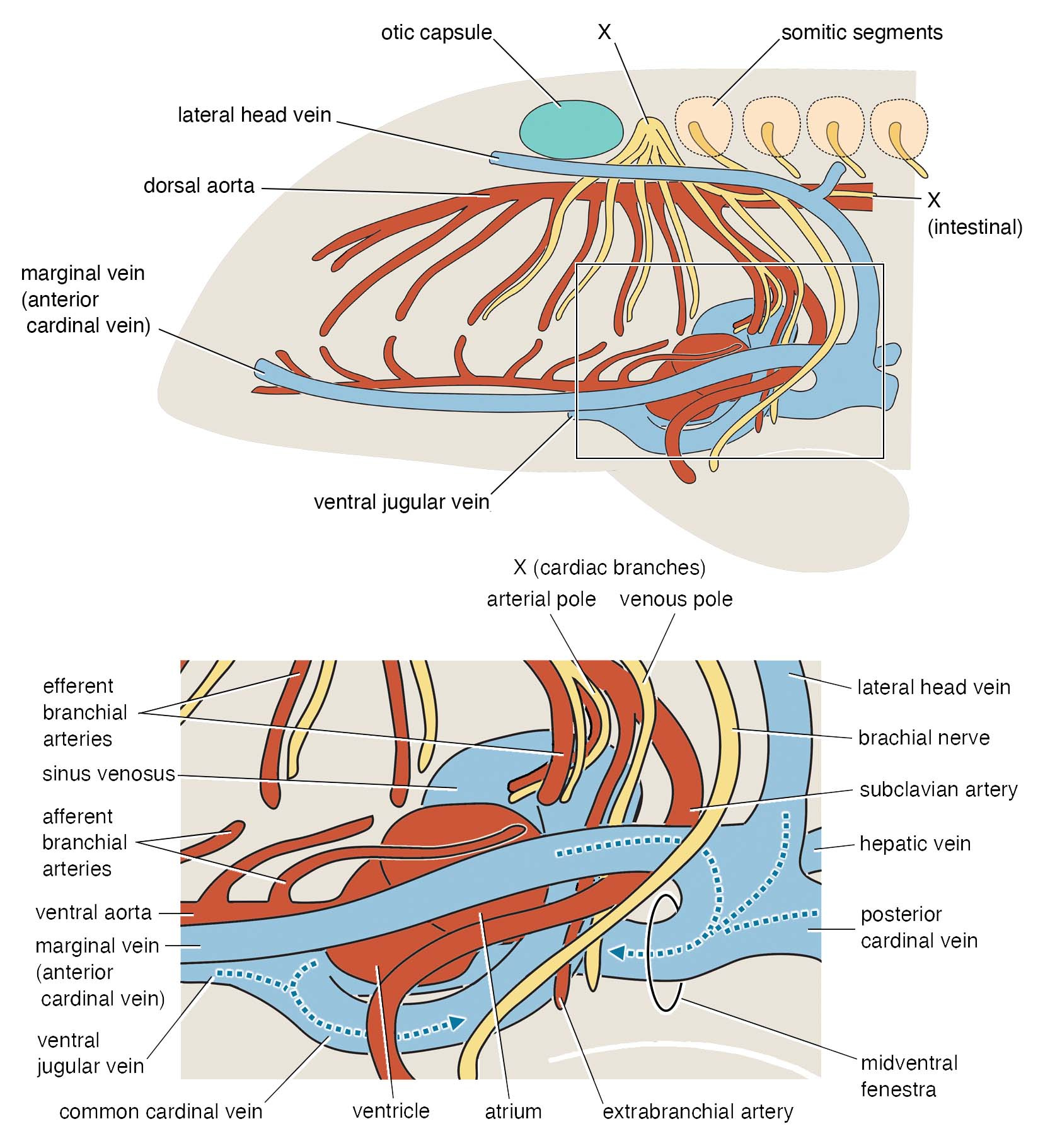

Or take the inner ears of Norselaspis, preserved without much distortion to reveal a specialized structure at the confluence of the semicircular canals and reconstructed to the mineral grains filling up the vestibule. These are both derived features of jawed vertebrate inner ears. We also found evidence for fine branches of the tenth cranial nerve that extend to the heart (called the cardiac branch of the vagus nerve). All this information is integrated to an astonishingly detailed understanding of the complex anatomy of the head-trunk interface in Norselaspis (see the diagram below).

But, of all the elements of the head-trunk interface as found in jawed vertebrates, Norselaspis is lacking any trace of the neck and throat muscles. Furthermore, the most anterior trunk nerve extends to the pectoral fins. This unique path hints at a startling perspective of serial homology. In the sister group of jawed vertebrates, the anterior somitic derivatives that would otherwise form the muscles in the neck and throat instead contributed to the pectoral fins. It also disrupts evolutionary continuity proposed for some muscles in lamprey as precursors for the neck and throat muscles in jawed vertebrates.

This innervation challenges the idea that the shoulder girdle evolved from the gill apparatus. The hypothesis had gained traction recently, citing shared cell lineages between the gills and shoulder among other inferences. We think Norselaspis provides clarity in sorting out evidence from interpretations. There is good evidence for skeletal or connective-tissue progenitors to be potentially opportunistic as to their fates, but axial identities of the structures are conserved because of the developmental programs that set spatial coordinates. These cells respond to the signalling environment that shapes the head-trunk interface, and out of the mass of neural crest and mesodermal cells migrating, proliferating, and differentiating, the nerve follows the chemical gradient that sets apart the head and trunk. As far as we can tell from Norselaspis, the shoulder girdle has always sat on the trunk side of the interface, distinct from the pharyngeal region.

Circles indicate morphologically comparable points of venous drainage between the two forms.

For Norselaspis, the most posterior cranial nerve (head domain) and the most anterior spinal nerve (trunk domain) are shown. The former sends its branches to the heart and intestine.

Illustration by Tetsuto Miyashita.

Norselaspis doesn’t fit the classical scenario for the origin of jawed vertebrates, either. The conventional wisdom is that jaws evolved first and that their functional advantage in capturing prey facilitated many other anatomical changes from jawless to jawed vertebrates, moving the latter up into the water column. But the suite of jawed vertebrate-like features in the jawless Norselaspis suggests the opposite. Jaws were a follower to the elaborate sensory systems, powerful heart, and greater locomotory control that already existed in the common ancestors between Norselaspis and jawed vertebrates. Now the evolutionary divide between them seems shorter than ever considered and rather diffuse.

Anatomical drawings by Tetsuto Miyashita.

Thus, the first jawed vertebrates may have been difficult to distinguish from osteostracans. Aside from having jaws, we expect them to feature only a few novel traits. These are functional correlates of mobile jaw skeleton –– neck and throat muscles and head-trunk joints –– must have greatly enhanced their abilities to generate suction current. Beyond these structures, our interpretation of Norselaspis predicts substantial overlaps between the last diverging jawless fishes and the earliest diverging jawed forms in appendicular, circulatory, nervous, and sensory anatomy. In this regard, our scenario presents a clear alternative to the linear, run-away evolution toward macropredators predicted by the standard “jaws first” scenario. To me, this insight, slowly developed as Mike and I discuss the new reconstruction, gave us the sense of “homerun” moment that this fossil is going to make an impact.

Illustration by Kristen Tietjen.

To return to the idea of a hypothetical intelligent lamprey, the easiest way to understand the ultimate implication of having a derived head-trunk interface is to ask what sports jawless fish can or cannot fundamentally play. There is nothing from a bauplan perspective that in principle keeps a well-trained osteostracan from making all basic moves of football, basketball, hockey and so on. However, in no way could it play baseball, for the same reason that a Blemmyai or Humpty Dumpty cannot, either. When a pitcher throws a ball, and when a batter lays a swing on it, their heads must stay in position while their bodies are making a quick recoil and torque, one foot stepping out, and hands moving forward. Otherwise, you cannot follow it to strike or ball. Baseball requires much greater differential movement between the head and trunk in its most fundamental plays.

Life restoration of Norselaspis by Kristen Tietjen. Drawing by Tetsuto Miyashita.

Biomechanically speaking, baseball is a game allowed only for jawed vertebrates, hexapods, and polychaetes (if their parapodia are strong enough to grip a ball or a bat) to partake. So I sit here in the stands with my little children to enjoy my gnathostome privilege again this evening, soaking up the glimmer of summer’s twilight, looking to the green turf and the blue-turning-purple sky, feeling gentle breeze carrying the smell of freshly grilled hotdogs and festive beer, with pops, cracks, cheers, and ooohs and aaahs, watching a bunch of Homo sapiens pitch, hit, and field a leathery spherical object put together by two red seams. When the fans rise in protest for balls and strikes, safe or out, I think about all the clearly defined boundaries in the Universe that nevertheless to human cognition could only be perceived or ruled as diffuse. Planets. Species. Head-trunk interface. I wonder, though, if anything in vertebrate anatomy could ever be as clearcut as judging a fair ball down the firm, glisteningly white baselines, and it would be much more straightforward in our career to score a run with truth, not just offer a set of ‘interpretations’. But then again, when David Ortiz would hook a flyball over the Pesky Pole in Fenway Park, who could truly tell with confidence it’s a foul or homerun?

Follow the Topic

-

Nature

A weekly international journal publishing the finest peer-reviewed research in all fields of science and technology on the basis of its originality, importance, interdisciplinary interest, timeliness, accessibility, elegance and surprising conclusions.

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in