Passing Traits Without Genes: How the Gut Microbiome Transfers Behavior

Published in Ecology & Evolution, Microbiology, and Biomedical Research

The under-appreciated partner in adaptation

What if organisms could respond to selection through their microbiome, without any changes in their genome? Our new research suggests that the trillions of microbes living inside animals can, on their own, drive changes in behaviour over time.

The microbiome, the community of microorganisms living in and on us, plays critical roles in development, metabolism, immunity, and even behavior. When we selectively breed animals for traits such as body size, milk production, or temperament, we are not only selecting their genes but also the microbiomes that come along for the ride.

Similarly, human populations adapting to new environments, whether colder climates, new diets, or emerging diseases, have undergone natural selection acting on both their genomes and their gut microbes. Yet traditional evolutionary theory has focused on host genes, assuming that changes in traits arise from changes in host genome.

But what if adaptive trait changes could work through microbes too? When animals adapt to new environments or are domesticated, both the host genome and the microbiome change. Because these two are so tightly linked, it has been nearly impossible to separate the contributions of host genetics and microbial influence to adaptive trait change.

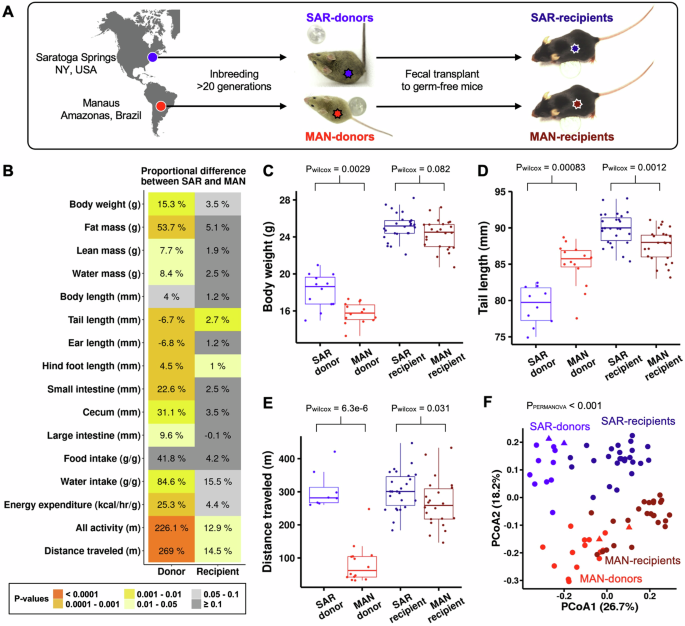

In our new study, we developed a way to overcome this challenge. Using genetically identical mice raised without any microbes (so-called germ-free mice), we conducted a series of fecal transplants, selectively transferring only the microbiome over time while keeping the host genome constant. Our goal was to ask: Can we select for a behavioural trait purely through the microbiome transmission?

Passing behavior through microbes

We began with a group of germ-free mice and introduced a microbiome from an individual mouse that showed high activity. In one group, the “selection” line, we took feces from the least active recipient mice and transferred their microbiome into a new set of germ-free mice. In another group, the “control” line, we transferred microbiomes at random, regardless of behaviour.

We repeated this process four times across four replicate lines, effectively creating a “microbiome-only” selection experiment. Every mouse in this experiment was genetically identical, differing only in the microbes they carried.

The results were striking. Over time, mice in the selection lines became less active than those in the control lines. This suggests that the microbiome itself was capable of transmitting and amplifying behavioural differences over time, without any change in the host genome.

When we analyzed the microbiome composition, one genus stood out: Lactobacillus. These bacteria and their metabolic byproducts, called indolelactic acid, were enriched in the selection lines and independently reduced activity levels in follow-up experiments.

Microbes as agents of adaptation

These findings have major implications for both evolutionary biology and biomedical research.

From an evolutionary perspective, this is evidence for microbiome-mediated adaptive plasticity—the ability of microbes to shape host traits in ways that could accelerate adaptation. In other words, animals (and humans) may not always need genetic mutations to adapt to new environments. Instead, changes in their microbial partners could rapidly alter behavior or physiology, potentially setting the stage for longer-term evolutionary change.

For domestication, this means that some of the traits we attribute to selective breeding, such as docility or reduced activity, might be driven in part by changes in the microbiome rather than the animal’s genome. This echoes emerging evidence from plants, where similar transfers of soil microbial communities influence crop traits such as flowering time and drought tolerance.

In biomedical research, our findings open the door to a new type of “microbiome engineering.” Just as we selectively breed for desirable genetic traits, we may be able to selectively breed microbial communities that produce beneficial effects on host health.

Behind the paper

Designing this experiment was an adventure in itself. We first needed to decide which traits to select for. To find out which aspects of physiology or behavior were most affected by the microbiome, we performed fecal transplant experiments using two distinct microbiomes and compared a wide range of traits in germ-free mouse recipients.

To our surprise, behavior (especially activity level) showed the strongest microbial influence, far more than morphological traits such as body weight or size. It was not an ideal choice from a researcher’s perspective; and although we used an automated cage system, measuring behavior in more than 300 mice is time-consuming. Selecting for an easier trait, like body weight, would have saved months of work. But the data were compelling.

One question people have asked us is, why did we select for mice that traveled less, as opposed to mice that traveled more? Ideally, we would have done both. But this would have meant three lines, because we had to keep the “randomly selected” line as a control. Space and time constraints forced us to choose between selecting high activity or low activity mice. We chose to select for low-activity mice because we knew that there was a dynamic range we could work with.

What followed was a long, carefully controlled experiment involving repeated microbiome transfers, behavioral assays, and metabolomic analyses to pinpoint microbial molecules linked to behavioral change.

In the end, observing genetically identical mice diverge in behavior simply because of their microbiome was exciting. It reminded us that the ability to respond to change is not confined to our genes alone—it is a story written in partnerships, shaped by the microbial ecosystems that live within us. And we are tempted to select in the other direction now, for microbiomes that increase activity.

Follow the Topic

-

Nature Communications

An open access, multidisciplinary journal dedicated to publishing high-quality research in all areas of the biological, health, physical, chemical and Earth sciences.

Related Collections

With Collections, you can get published faster and increase your visibility.

Women's Health

Publishing Model: Hybrid

Deadline: Ongoing

Advances in neurodegenerative diseases

Publishing Model: Hybrid

Deadline: Mar 24, 2026

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in