Reorganisation of North Atlantic Atmospheric Circulation Patterns due to Anthropogenic Warming

Published in Earth & Environment and Mathematics

The weather over the North Atlantic affects hundreds of millions of people. From winter storms over Europe to cold spells in eastern North America, many of these impacts are shaped by large-scale atmospheric circulation patterns that recur repeatedly. Climate scientists refer to these preferred patterns as atmospheric regimes.

One of the most influential of these regimes is the North Atlantic Oscillation (NAO), a seesaw in atmospheric pressure between the subtropical Atlantic and Iceland that governs wind strength, storm tracks, and temperature patterns across the region. Yet a fundamental question has remained open for decades: how does anthropogenic climate change affect these atmospheric regimes and their variability?

Our recent study, published in Communications Earth & Environment, set out to answer this question (https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-026-03180-0).

The big challenge: separating forced change from natural variability

One of the hardest problems in climate science is distinguishing human-driven change from the climate system’s own internal variability. Atmospheric circulation naturally fluctuates on timescales from weeks to decades, even without any external forcing. This makes it difficult to tell whether observed changes reflect global warming or just natural variability.

Earlier studies often relied on single climate model simulations or short observational records. But these approaches can blur the signal, especially for phenomena like atmospheric regimes that are inherently noisy.

To overcome this, we used 100 simulations from the Community Earth System Model Large Ensemble (CESM2-LE). Each simulation experiences the same external forcing, i.e., greenhouse gases, aerosols, and volcanoes, but starts from slightly different initial conditions. This allows us to cleanly separate:

- The forced response (the part driven by anthropogenic warming), and

- Internal variability (the climate’s natural fluctuations).

This distinction turned out to be crucial.

A key turning point in the mid-1990s

Rather than assuming climate change acts gradually, we asked a simple but powerful question: when does the imprint of anthropogenic warming become detectable in the North Atlantic circulation?

Using a statistical changepoint detection method, we found a clear signal emerging around 1995 in mid-tropospheric circulation patterns. This motivated us to split our analysis into two periods:

- Pre-1995, when anthropogenic influence was weak, and

- Post-1995, it becomes dominant.

This allowed us to directly compare atmospheric regimes before and after the emergence of the climate change signal.

What stays the same and what changes dramatically?

One of our most striking findings is a contrast between structure and organisation.

When we include the forced response, the number of North Atlantic atmospheric regimes remains the same before and after 1995. At first glance, this might suggest little change. However, upon closer examination, we discovered something far more intriguing.

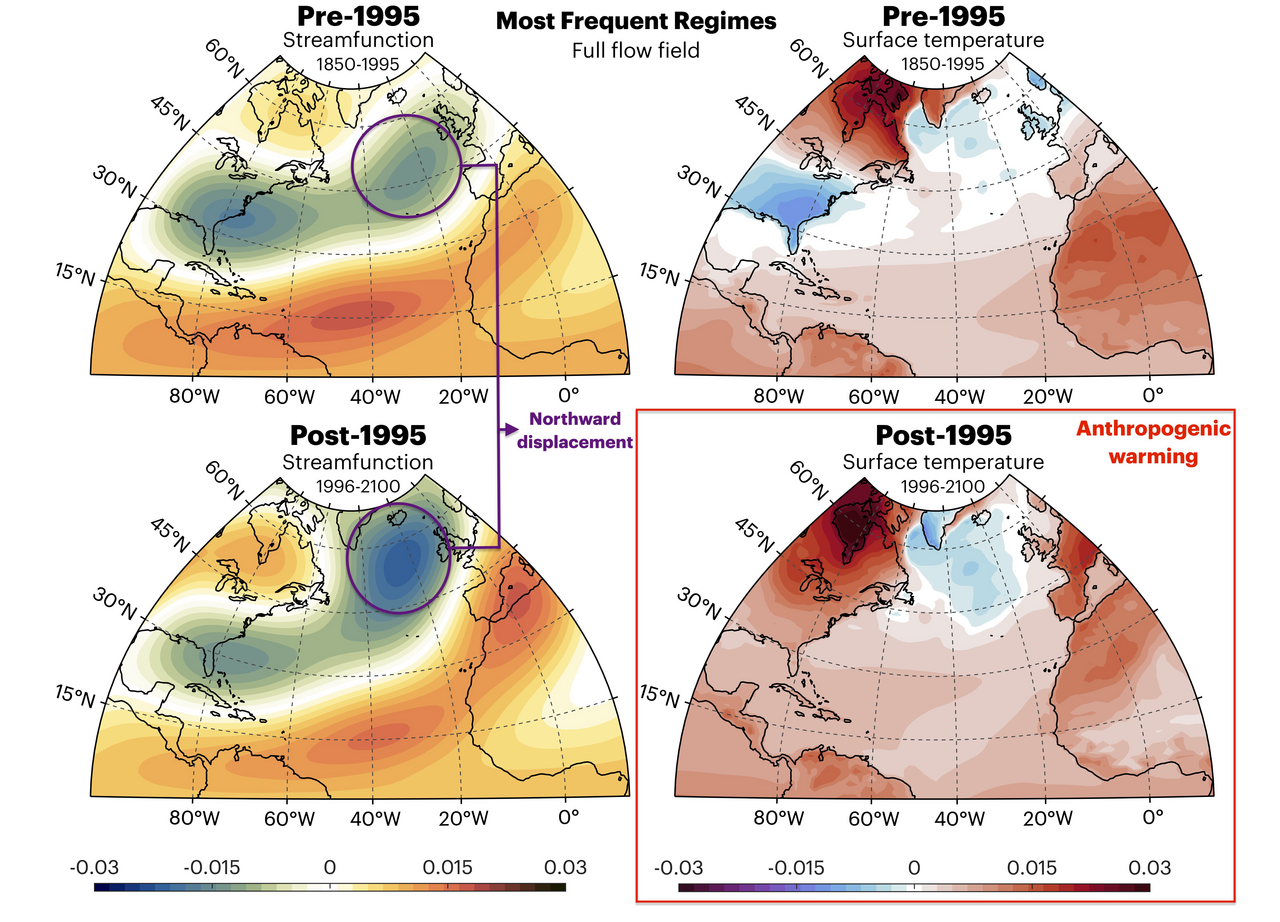

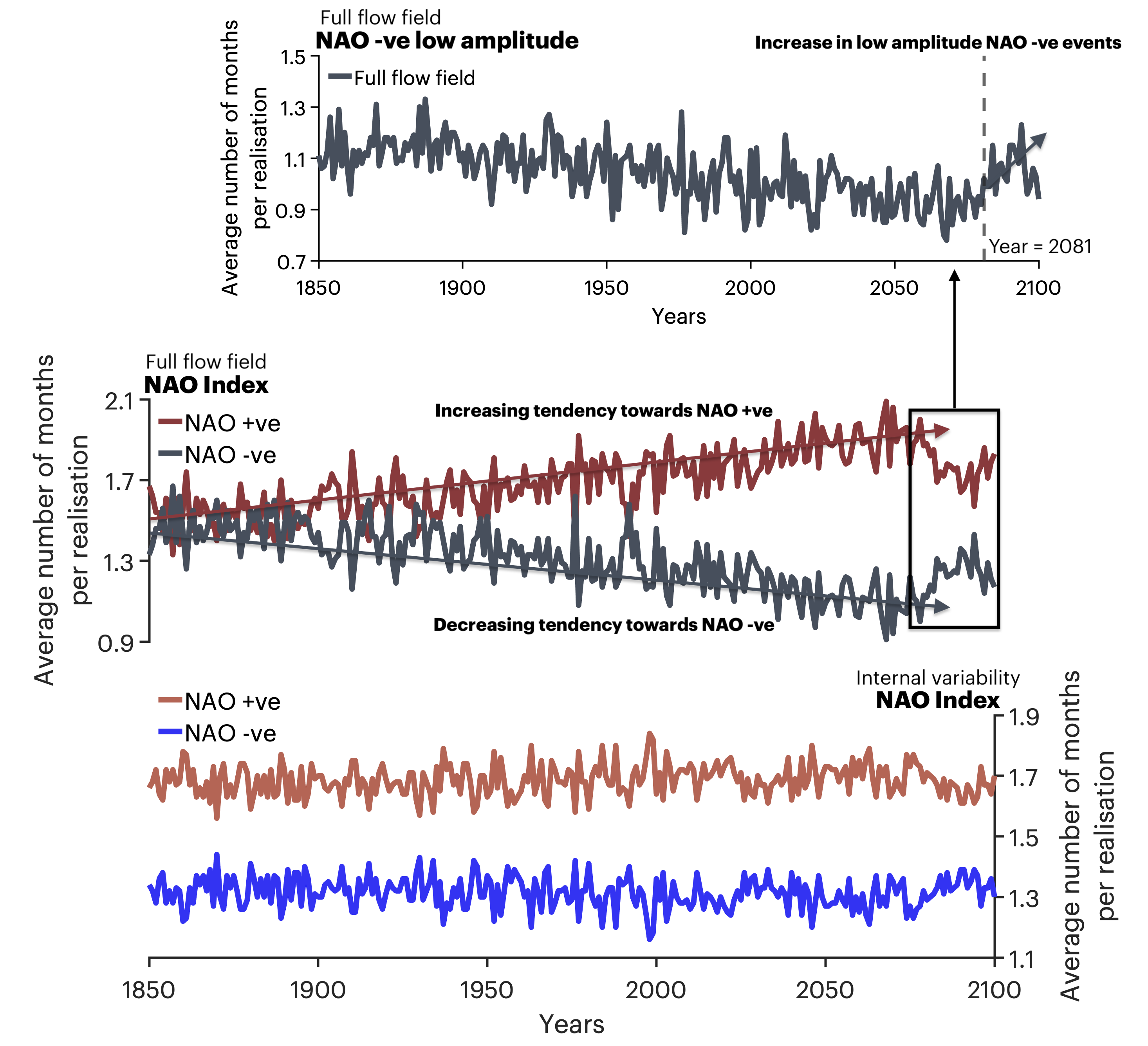

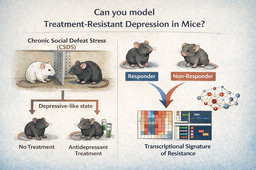

While the number of regimes stays constant, their spatial patterns reorganise under global warming. The centres of high and low pressure shift northward, circulation intensifies in some regimes, and the balance between different patterns changes. A prominent example of the most frequent regime state can be observed in Figure 1, where a clear northward displacement of low pressure region is evident in the period after 1995, during which anthropogenic warming is expected to dominate. In other words, climate change does not destroy the regimes; it reshapes them.

In contrast, when we remove the forced response and look only at internal variability, the picture is very different. The number of regime states decreases after 1995, and one dominant regime becomes much more persistent. This suggests that anthropogenic warming is suppressing part of the natural variability of the atmosphere.

A future tilted toward a positive NAO

The North Atlantic Oscillation plays a central role in this story.

We find that under anthropogenic forcing, the NAO shows a subtle but detectable shift toward more positive phases during most of the 21st century. Positive NAO phases are associated with stronger westerly winds, milder winters in northern Europe, and wetter conditions in some regions.

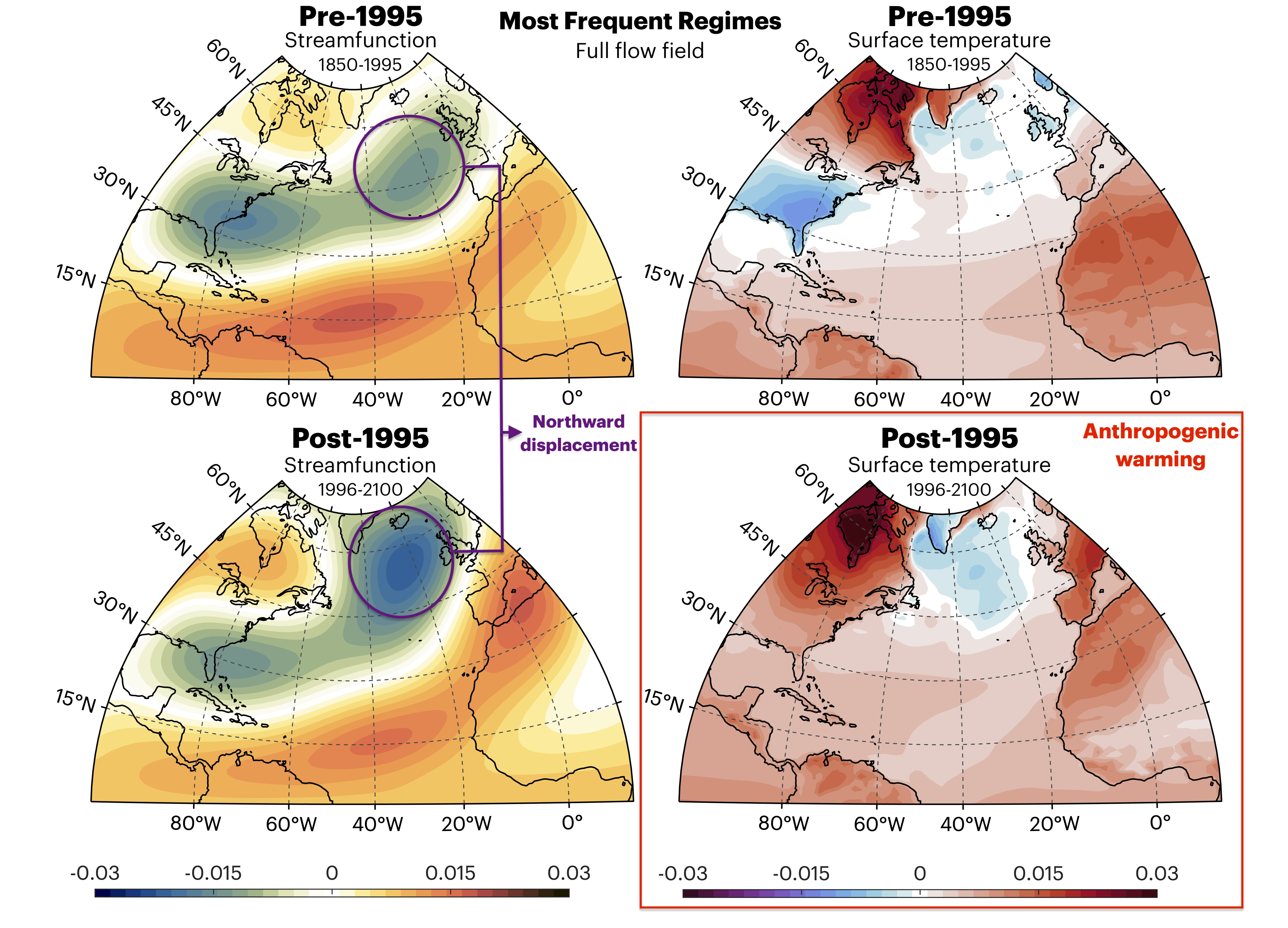

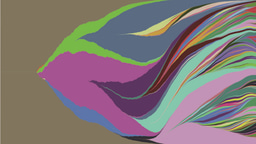

At the same time, the overall variability of the NAO declines. This means fewer strong swings between positive and negative phases. Interestingly, toward the end of the century, this trend partially reverses, not because strong negative events increase, but because low-amplitude negative NAO phases become more frequent (Figure 2).

Figure 2 illustrates the increasing tendency towards NAO-positive phases, accompanied by a decrease in the low-amplitude NAO-negative phases after the year 2081, following anthropogenic warming.

This nuanced behaviour would have been impossible to detect without a large-ensemble approach. Dynamically, these changes are closely linked to the mid-tropospheric jet stream. We find that warming strengthens the jet in NAO-positive regimes while weakening it in NAO-negative ones, reinforcing the asymmetry between phases.

Why this matters beyond climate models

Atmospheric regimes shape real-world impacts. Changes in their frequency, persistence, and structure influence:

- Winter storm tracks

- Temperature extremes

- Precipitation patterns

- Wind energy potential

- Risks to ecosystems and infrastructure

Our results suggest that future North Atlantic climate variability will not simply be “more of the same, but warmer.” Instead, it will be characterised by reorganised circulation patterns, altered regime transitions, and damped natural variability.

This has significant implications for seasonal prediction, climate risk assessment, and adaptation planning, particularly in Europe, eastern North America, and the Arctic.

Looking ahead

Our study focused on one climate model and a high-emissions scenario. An important next step is to examine whether similar regime reorganisations occur across multiple models and emission pathways.

More broadly, our work highlights the power of combining large ensembles, regime-based analysis, and dynamical interpretation to better understand how climate change reshapes atmospheric variability not just its mean state, as the atmosphere is being quietly reorganised.

Follow the Topic

-

Communications Earth & Environment

An open access journal from Nature Portfolio that publishes high-quality research, reviews and commentary in the Earth, environmental and planetary sciences.

Related Collections

With Collections, you can get published faster and increase your visibility.

Climate extremes and water-food systems

Publishing Model: Open Access

Deadline: May 31, 2026

Archaeology & Environment

Publishing Model: Hybrid

Deadline: Mar 31, 2026

Latest Content

Why is Singapore Identified in Global Research as Number One? How Physical Activity and Education Excellence Created a Global Leader

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in