Repurposing a Simplified Diagnostic Tool to Increase Screening for HBV and HCV in Resource-limited Settings

Published in Public Health

Hepatitis B (HBV) and C (HCV) infections are a public health threat, affecting an estimated 254 million and 50 million people, respectively. Particularly, in sub-Saharan Africa (sSA), HBV is widespread, and HCV is no exception. It too poses a significant problem for the African population. According to figures provided by the World Health Organization (WHO), about 6% of sSA communities are HBsAg positive, whilst HCV prevalence ranges from 1% to 2%.

But, what if we could use already existing tools or approaches in other diseases to help reduce the current burden of viral hepatitis? In today’s blog post, we dive into the motivations and trademark features of a novel study that took place in both Uganda and Cameroon between May 2021 and March 2023, and what it could mean for those undiagnosed with either HBV or HCV. Read more below!

What inspired this study?

We started this study because the PI was intrigued by the plasma separation card (PSC), which he saw presented at a conference, and its potential applications. At that time it was not in use in the field for viral hepatitis, only having been recently validated in a laboratory in Barcelona.

Its capability to collect dried blood samples to monitor HIV viral loads got us thinking that, perhaps, this could work for other diseases and in resource-limited areas like Cameroon and Uganda, where it is not easy to perform phlebotomies (drawing blood). However, not only could the PSC be transported and store samples without the need to be maintained in cold chain, but it would not require further centrifugation plasma separation. Also, sampling could be carried out via whole capillary blood obtained by fingerstick.

This then led us to carry out a real-world study and examine the feasibility and acceptability of the PSC in viral hepatitis testing. With context-adapted and simplified screening methods, screenings overall could rise and possibly result in a higher number of timely diagnoses.

In the case of viral hepatitis infections, this was extremely important to us. Although the World Health Organization (WHO) set elimination targets, timely screening and diagnosis for viral hepatitis remains the main obstacle in reaching these objectives.

Why is this study important?

Countries with mid- and high prevalence of viral hepatitis infections often find themselves with scarce resources for healthcare. This results in a substantial hurdle for establishing accessible screening opportunities. Both late diagnosis of viral infection and their subsequent late access to adequate care mean that those with either HBV or HCV can face life-threatening conditions–all of which are preventable.

Our desire to explore feasible and affordable diagnostic tools would not only represent a step towards promoting equitable access and screening services, but it would also entail improving health outcomes overall.

But, there is more. We wanted to maximise the potential impact and implementation of these diagnostic tools, so we also explored patients’ perspectives, experiences and preferences.

What makes this study unique?

This study was unique because it recognised that introducing a new point-of-care test would be meaningless if patients themselves were reluctant to accept such an approach.

Our study further contributed to closing the existing gap in current research and literature in SSA.

Did this study show anything unexpected?

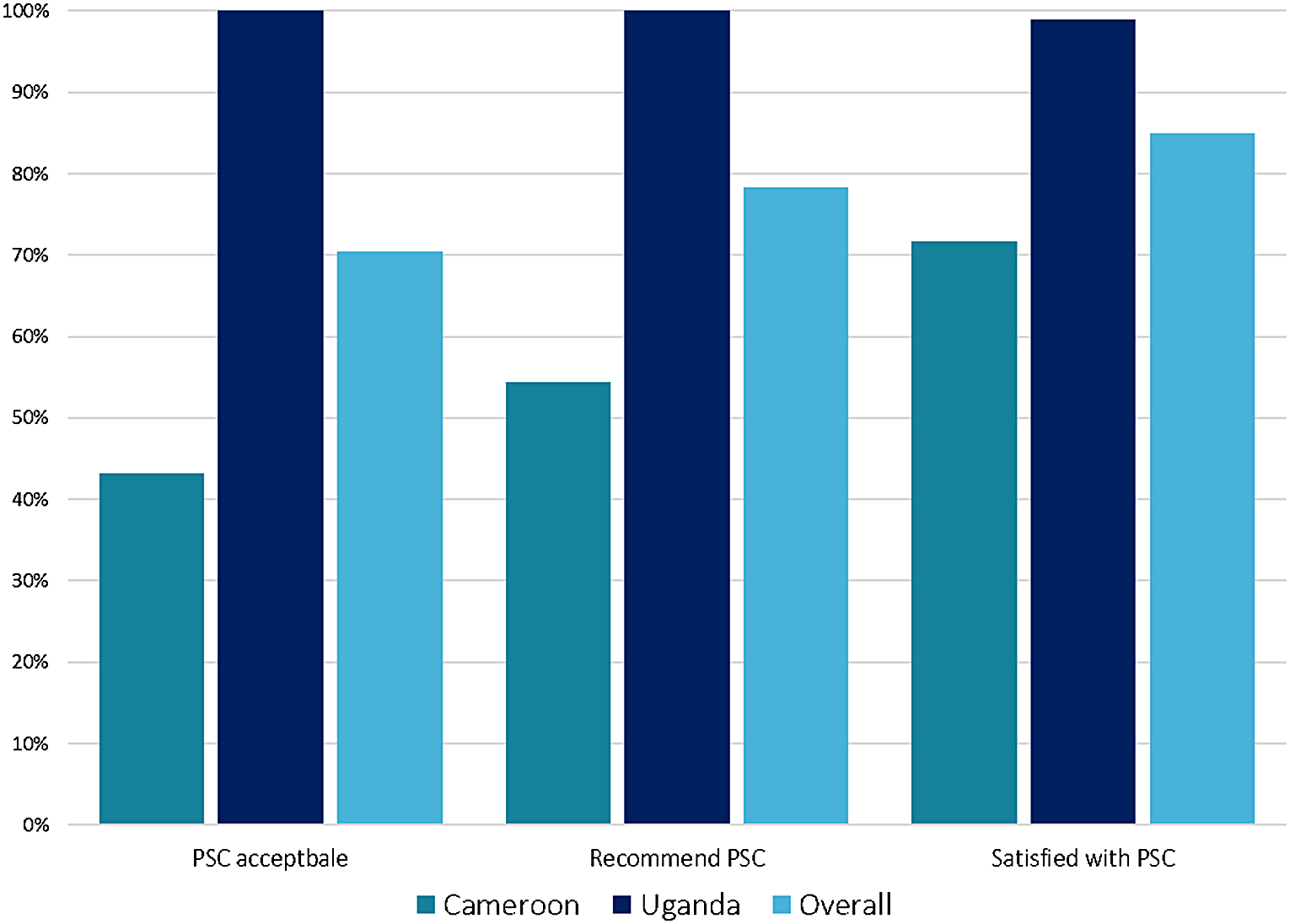

Although not unexpected per se, we did find that there were major differences between the countries on acceptability of the PSC method (100% in Uganda vs 43% in Cameroon). This suggests that once again, there is no one-size-fits-all.

“The PSC method could be feasible for viral hepatitis testing, but acceptability thereof is not always guaranteed. Exploring these variations, like in the case of Cameroon and Uganda, implies enhancing care according to the person, and not just to the infection.”

What is the wider significance of the study’s findings?

One take-away is that we can develop and integrate simplified diagnostic tools effectively in resource-limited settings.

Secondly, by exploring insights from clients (aka patients), we can form strategies that better match the needs of different communities and help make sure that interventions both work and are well-received.

Finally, it’s worth mentioning that this study is another contributing piece to our research team’s extensive work on understanding and implementing simplified diagnostic tools for viral hepatitis infection screenings. For example, as part of a EU-funded project “Viral Hepatitis COMmunity Screening, Vaccination, and Care (VH-COMSAVAC)”, we were able to screen around 1,000 migrants in Catalonia, Spain, using PSCs–alongside rapid diagnostic tests (RDTs)–to examine HBV viral load and hepatitis D virus (HDV) antibodies, and identify past-resolved HBV infections.

Overall, there is much more to explore with the use of PSCs in resource-limited settings, like that of HIV clinics in Uganda and Cameroon, and in community-based settings in Spain as well. More related work can be found below:

- Picchio CA, Kwakye DN, Rando-Segura A, et al., Lazarus JV. Community-based screening enhances hepatitis B virus (HBV) linkage to care among West African migrants in Spain. Communications Medicine 2023.

- Picchio CA, Kwakye DN, Gómez Araujo S, et al., Lazarus JV. A novel model of care for simplified testing of HBV in African communities during the COVID-19 pandemic in Spain. Scientific Reports. 2021.

- Lazarus JV, Herranz A, Picchio CA, et al. Eliminating hepatitis C on the Balearic Islands, Spain: a protocol for an intervention study to test and link people who use drugs to treatment and care. BMJ Open. 2021.

- MacKinnon MJ, Picchio CA, Kwakye DN, et al., Lazarus JV. Chronic conditions and multimorbidity among West African migrants in greater Barcelona, Spain. Frontiers Public Health. 2023.

Follow the Topic

-

Journal of Epidemiology and Global Health

The journal aims to impact global epidemiology and international health with articles focused on innovative scholarship and strategies to advance global health policy.

Related Collections

With Collections, you can get published faster and increase your visibility.

Infectious disease outbreak in conflict-driven displacement: challenges, responses and future

Infectious disease outbreaks are increasingly entwined with conflict, forced displacement, and fragile health systems. In recent years, cholera in Yemen, measles among displaced Rohingya, and COVID-19 in Syrian camps have revealed how conflict-driven migration and humanitarian crises amplify the risks of large-scale epidemics.

Overcrowding, collapsing health infrastructure, disrupted supply chains, rise of anti microbial resistance (AMR) and constrained access to care create fertile conditions for rapid transmission, particularly among migrants and refugees.

Despite growing recognition of these intertwined vulnerabilities, evidence remains fragmented, and the operational and policy frameworks required to mitigate these crises are often reactive rather than anticipatory. This collection aims to consolidate case studies, field data, and solutions to better understand, prepare for, and respond to infectious disease outbreaks among displaced populations in conflict-affected settings.

Key Topics

1. Epidemiology of Infectious Diseases in Conflict Settings:

• Burden and patterns of infectious diseases (e.g., cholera, tuberculosis, malaria, measles, and respiratory infections) in conflict-driven displacement.

•Transmission dynamics in over-crowded camps, urban conflict settings, and transit corridors.

•Impact of armed conflict and forced displacement on AMR dynamics.

•Case studies from acute and protracted conflicts (e.g., Syria, Yemen, Sudan, and Central African Republic).

2. Vulnerabilities of Forcibly Displaced Populations:

•Health disparities caused by malnutrition, poor sanitation, and disrupted care.

•Gender, age, and disability-related vulnerabilities in accessing health services.

•Access to care barriers due to security risks, mobility, legal status, and cultural challenges.

3. Health System Collapse and Humanitarian Responses:

•Impacts of weakened health infrastructure, fragmented governance, and security constraints on disease control.

•Strategies for disease surveillance, vaccination campaigns, and WASH interventions in volatile environments.

•Innovations in service delivery: mobile clinics, telemedicine, and community-led response models.

•Role of local actors and international humanitarian organizations in outbreak response.

4. Policy, Law and Future Preparedness

•Intersection of human rights law, refugee law, and international health regulations in managing outbreaks.

•Challenges in cross-border coordination, governance, and resource mobilization.

•Policy recommendations for anticipatory action and resilient health security systems in conflict and displacement settings.

All submissions in this collection undergo the journal’s standard peer review process. Similarly, all manuscripts authored by a Guest Editor(s) will be handled by the Editor-in-Chief. As an open access publication, this journal levies an article processing fee (details here). We recognize that many key stakeholders may not have access to such resources and are committed to supporting participation in this issue wherever resources are a barrier. For more information about what support may be available, please visit OA funding and support, or email OAfundingpolicy@springernature.com or the Editor-in-Chief.

Publishing Model: Open Access

Deadline: Jun 26, 2026

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in