Spring 2020 started with a bang; how did it wind up?

Published in Ecology & Evolution

In the southeast US, the start of spring 2020 was really early – in some places, the earliest in the last four decades. But once spring started, did it stay ahead of schedule, racing through typical onsets like first leaf in maples, oaks, and poplars, and emergence of beetles, moths, and butterflies ahead of schedule throughout spring?

In my role as the director for the USA National Phenology Network, an organization focused on tracking and sharing information on the timing of seasonal biological events such as leaf-out and flowering, I have received several reports recently from various parts of the country of spring dragging out and lasting for a remarkably long time. In Washington, DC, an observer reported that leaf-out in deciduous trees had been ongoing for nearly eight weeks; in parts of upstate New York, late spring-season activity is the latest in the last decade.

This caused me to wonder: how does the shape of spring this year – not only the timing of when it started, but also how long it lasted - compare to what we consider to be “normal”?

Winter and spring temperatures are the driving force

In much of the U.S. and the world, the initiation of springtime biological activity is driven by springtime warmth. A common approach for predicting when plants and animals will begin springtime activity like leaf-out and emergence is to track how warm it has been in recent months. In particular, the accumulation of warmth over a period of time is what appears to have the greatest influence on biological activity.

If we envision the spring season as a continuous accumulation of warmth over several months, we can use a low heat accumulation to represent the start of the season and a higher amount to represent the transition of spring into summer.

We can then look at when those heat accumulations are typically met and compare that to when they occurred this year to get a sense of whether 2020 has been different from “normal”.

To evaluate the spring of 2020, we looked at two heat accumulation totals – one representing the very leading edge of spring warmth, associated with very early-season events such as first bloom in silver maples, and another associated with events occurring near the latter part of the spring season, such as full bloom in flowering cherry trees and viburnums, first flower in Ohio buckeyes and horse chestnuts, and dandelions going to seed.

Was the spring of 2020 special?

Typically, the length of time between the conditions associated with these springtime events occurring is between eight to 10 weeks in much of the contiguous U.S.

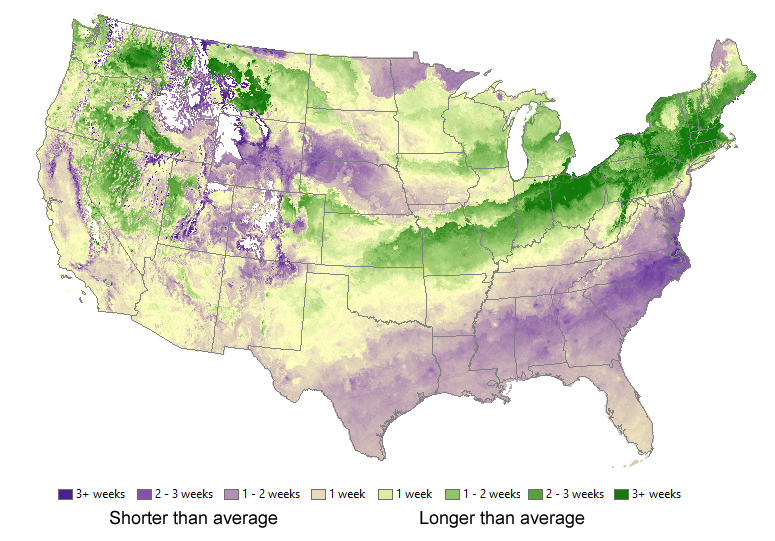

This year, the duration between these parts of the season was four or more weeks longer than normal in much of the Northeast, and northern Ohio and Indiana (green areas on the map).

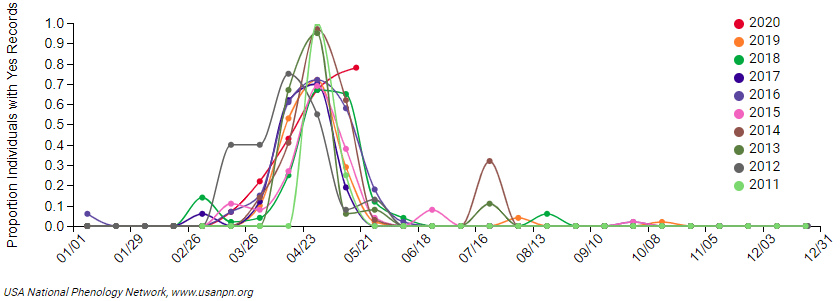

Reports to Nature’s Notebook, the USA National Phenology Network’s plant and animal phenology observing program, reveal similar patterns in plants and animal activity. In New York, leaf emergence and elongation was still being reported in late May in, a full month later than in the previous nine years.

Reports of leaf emergence in maples (Acer spp.) in New York, 2011-2020, submitted to the USA National Phenology Network’s community science program, Nature’s Notebook. The peak in leaf emergence is noticeably later in 2020 (red line) than in all previous years.

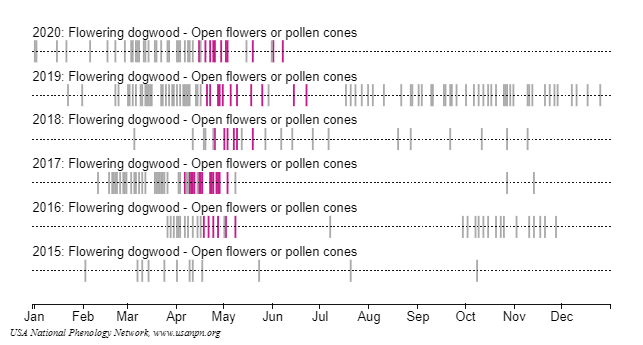

In the Washington, D.C. region, flowering dogwoods boasted open flowers weeks later into the season than in most recent years.

Reports of open flowers in flowering dogwood (Cornus florida) in the Washington, D.C. region, 2015-2020, submitted to m, Nature’s Notebook.

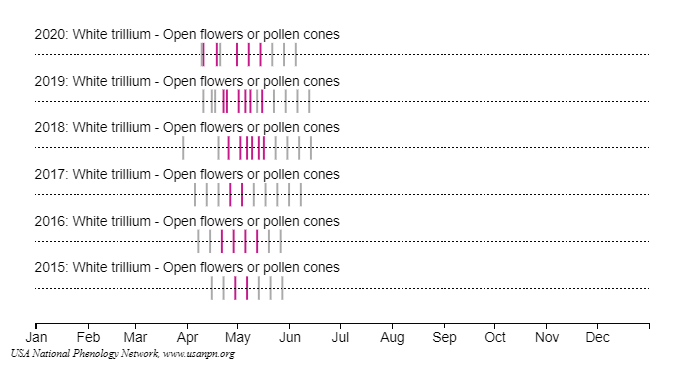

And in northern Ohio and Indiana, white trilliums flowered for longer than in any of the previous five years. The earlier portion of the spring season certainly seemed stretched out in these parts of the country.

The rest of the country didn’t experience such a long spring. In the Southeast, the length of time between the beginning of warmth and the transition to later spring conditions was one to two weeks shorter than normal.

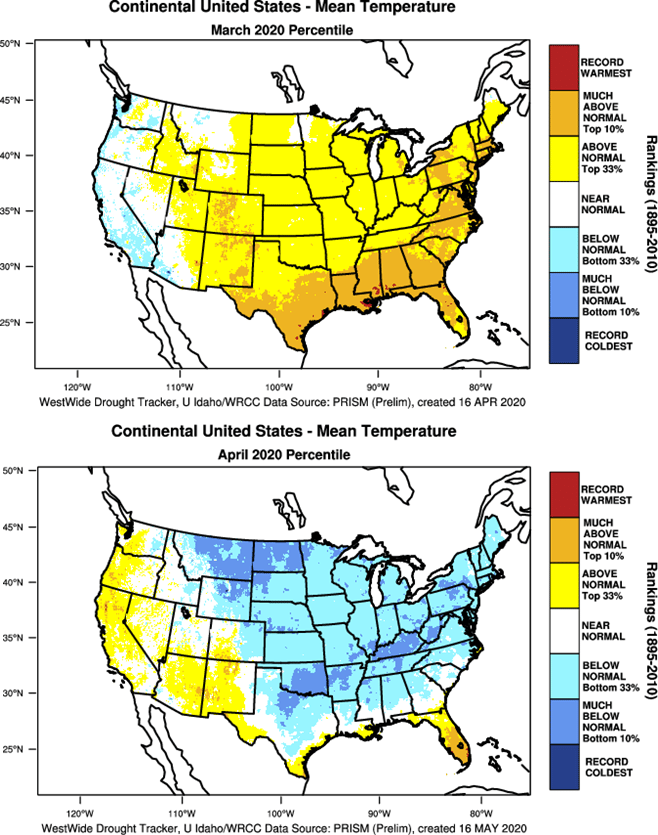

The primary driving force behind these patterns was the evolution of warm and cool spells throughout the early spring season. A strongly positive Arctic Oscillation kept cold polar air restricted to Canada in March, allowing unusually warm temperatures to flourish across the eastern U.S. These warm temperatures caused rapid accumulation of warmth in southern states and drove earlier-than-average phenological activity in the region. This weather pattern broke down in April, when cooler-than-average temperatures were observed from the northern Great Plains to the central and eastern U.S. The rapid accumulation of warmth that occurred in March was effectively paused as cooler conditions persisted through April.

source: WestWide Drought Tracker

And, though spring was longer than normal in the Northeast this year, stretched-out seasons like these aren’t unheard of. Similarly “stretched out” springs in the Northeast occurred in 2001, 2003, 2010, and 2015. These years were similarly characterized by anomalous early-season warmth followed by cooler temperatures and a mid-spring stall in warmth accumulation.

So what?

The early start to spring in much of the south and east this year had dramatic and visible impacts, including an early start to the allergy season, increased frost risk to specialty crops, and an earlier emergence of turf, garden, and landscape pests. But the flip conditions from March to April, resulting in a dramatic slowdown in warmth accumulation and a "stretched out" spring in the Northeast was noteworthy. And in the rest of the country, the length of the spring season was pretty typical.

Whether the seasons starts early is one thing… but how it plays out is another story. The length of the spring this year was noticeable in parts of the Northeast and Midwest; otherwise, not that remarkable.

Technical notes

The length of season was estimated by comparing the duration in days between 50 growing degree days and 450 growing degree days (base 0°C temperature; growing degrees calculated in Celsius) in 2020 to the long-term average duration (1981-2010).

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in