The architectonics of cancer tissue: a “bulk” analytical framework to study cancer tissue organization

Published in Cancer

Histopathology is the cornerstone of clinical diagnosis for solid cancer, in which cancerous lesions are identified as a structural deviation from normal tissue. This is possible because normal tissue is patterned in a way conducive to its physiological function, with many mechanisms (both cell-autonomous and non-autonomous) to ensure that its architecture is properly maintained. It is now widely appreciated that cancer cells acquire and evolve various “hallmark” features to evade these mechanisms—such as the ability to invade surrounding tissue and to resist immune destruction.

What is less clear, however, is whether there are recurrent patterns in cancer tissue architecture: are cancers simply randomly “broken” normal tissue, or do they possess an underlying architectural logic of their own? If such a logic underlying cancer tissue architecture exists, what would this “architectonics” of cancer tissue teach us about cancer pathogenesis or treatment response?

A novel analytical framework for a pan-cancer perspective

We sought to answer this question by analyzing bulk RNA-sequencing (RNA-seq) data. Given our interest in tissue architecture, which is inherently spatial, the use of bulk RNA-seq data—where spatial information is largely lost—may seem counterintuitive. We reasoned, however, that the reliance of traditional cancer histopathology on the tissue-of-origin as a reference would complicate pan-cancer comparisons. Although spatial omics techniques are advancing quickly, large-scale data acquisition remains challenging.

In contrast, deriving a quantitative index of cancer tissue architecture from bulk RNA-seq would allow us to:

1) leverage large, publicly available databases such as The Cancer Genome Atlas project (TCGA) for a pan-cancer analysis

2) quantitatively stratify patients and assess the clinical significance of different tissue architectures

3) correlate our findings with emerging spatial omics data to bridge the gap between the obtained numerical index and spatial patterns.

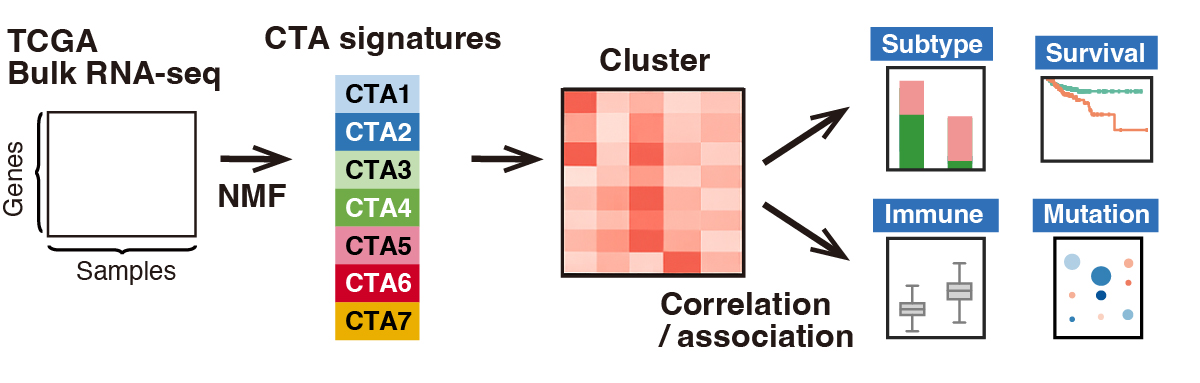

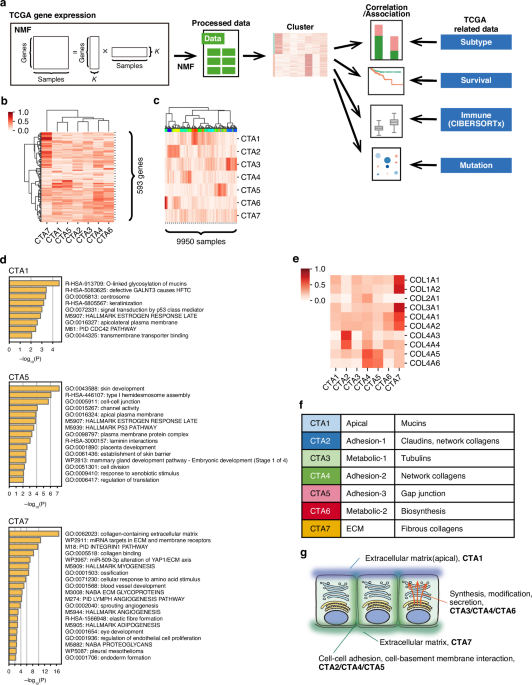

To this end, we first curated a set of 593 genes (the “cancer tissue architecture [CTA] gene set”) from the Molecular Signatures Database using the keyword “extracellular matrix”. We focused on the extracellular matrix (ECM) given its pivotal role in dictating tissue architecture and its dysregulation in cancer. Using the CTA gene set, we then applied a computational method called non-negative matrix factorization (NMF) to the TCGA RNA-seq data (9,950 samples spanning 28 cancer types). This allowed the identification of seven gene signatures (CTA1-7) and the derivation of two matrices: Matrix #1 indicating the gene expression profiles for the signatures, and Matrix #2 indicating the intensity of the seven gene signatures for each of the 9,950 cases (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Overall study design

Decoding the biological meaning of the CTA signatures

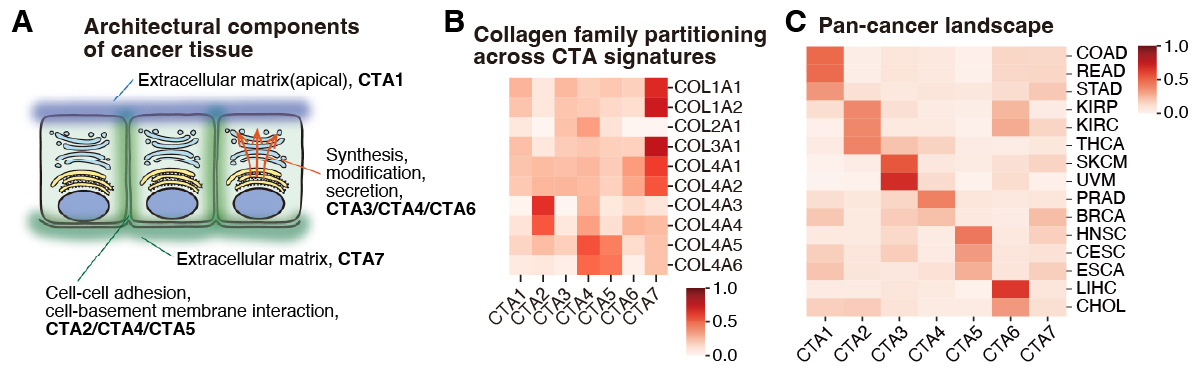

What do the seven CTA signatures mean? We inspected Matrix #1 to answer this (Figure 2A). Although NMF only utilizes gene expression levels (i.e., agnostic of function or localization), gene ontology analysis of genes enriched in each signature revealed functional specialization and compartmentalization. For example, CTA1 was enriched in mucins, whereas CTA5 in gap junctions and CTA7 in fibrous collagens (Figure 2B). Notably, even genes belonging to the same superfamily were differentially enriched depending on function (e.g., network collagens in CTA2 and CTA4 versus fibrous collagens in CTA7).

Figure 2. Biological features and pan-cancer landscape of the CTA signatures

The functional specialization and compartmentalization of the identified signatures suggest that they each capture different aspects of tissue architecture (Figure 2C). We thus reasoned that the intensity profile of these signatures (Matrix #2) could serve as a quantitative index of cancer tissue architecture. Indeed, comparison of average signature intensities across cancer types revealed that some are fairly ubiquitous (e.g., CTA7), while others are highly cancer-type-specific, such as CTA1 (prominent in adenocarcinomas of gastrointestinal organs), and CTA2/CTA6 (renal cell carcinoma).

Interestingly, we also observed similarities spanning different tissues-of-origin, such as between squamous cell carcinomas of various organs (dominant CTA5 signature), and between kidney renal cell carcinoma and thyroid carcinoma (prominent CTA2). Thus, the CTA signatures capture both shared and unique features of cancer tissue architecture across various cancer types. Importantly, we also validated these findings using RNA-seq data from the Pan-Cancer Analysis of Whole Genomes (PCAWG) project.

Drivers of unique CTA signature profiles

What determines the differential CTA signatures between cancer types? Analysis of Genotype-Tissue expression (GTEx) data from normal tissues yielded results reminiscent of cancer tissues, such as high CTA1 in gastrointestinal organs and high CTA2 in the kidney. This suggested that the tissue-of-origin, to an extent, constrains the CTA signature of the resultant cancer. However, cancer-specific aberrations were also observed—most notably the diminution of CTA4 intensity—indicating additional disease-specific processes that drive the acquisition of a tissue architecture unique from the tissue-of-origin.

Notably, analysis of the Cancer Cell Line Encyclopedia (CCLE) dataset revealed patterns similar to those observed in the TCGA and PCAWG datasets. The fact that cancer cells in culture, devoid of a tissue context, recapitulate most of the CTA signature profile suggests that cancer cells are the chief orchestrators driving these differential CTA signature profiles. We further corroborated this notion by revealing correlations between specific genomic alterations (such as mutations in CDH1 or TP53) in cancer cells and CTA signature intensity. However, we also noticed that the CCLE data overall lacked CTA7, suggesting that other cells (such as fibroblasts) within the tumor microenvironment are required to fully achieve the characteristic CTA signature.

Biological and Clinical Relevance: From Patient Stratification to Cancer Immunophenotype

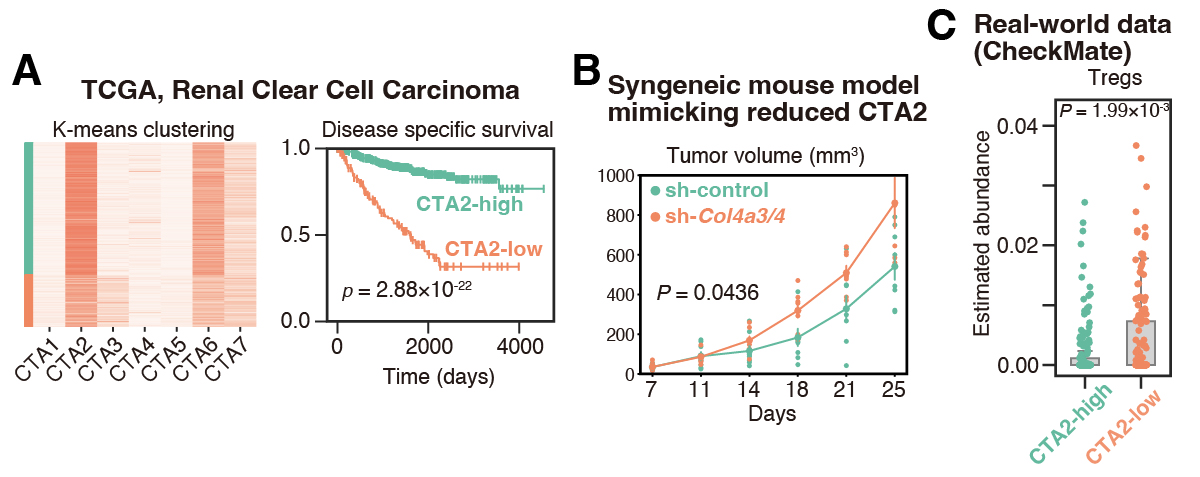

Finally, we asked whether the CTA signatures are useful for patient stratification. We performed an in-depth analysis on kidney renal cell carcinoma, where patients could be clustered into two groups based on CTA2 intensity (high versus low), with CTA2-low patients demonstrating a significantly worse prognosis (Figure 3A).

To test for a causative relationship, we developed a murine model. Given that COL4A3/4 genes are representative of CTA2, we generated Col4a3/4-knockdown RenCa (murine renal cancer) cells. While this knockdown did not affect cancer growth in immunodeficient mice, it accelerated growth in immunocompetent mice, suggesting the acquisition of an immune-evasive mechanism (Figure 3B). Indeed, Col4a3/4 knockdown increased regulatory T cell presence in the tumor.

This finding was further corroborated using RNA-seq data from patients with advanced kidney renal cell carcinoma who received PD-1 blockade therapies: CTA2-low (corresponding to Col4a3/4 knockdown in mice) patients demonstrated higher levels of regulatory T cell infiltration (Figure 3C). Thus, CTA signatures may be useful in identifying clinically relevant patient subgroups with differing prognoses.

Summary and future outlook

Our simple but versatile analytical framework leverages bulk RNA-seq data to obtain biologically and clinically relevant information regarding cancer tissue architecture, successfully revealing recurrent patterns across diverse cancer types and differential patterns within a cancer type. Although further work correlating differential CTA signature intensities with histopathology and refining the CTA gene set are warranted, a fuller understanding of the architectonics of cancer tissue will likely yield useful biomarkers for cancer diagnosis, classification, and targeted therapies.

Follow the Topic

-

British Journal of Cancer

This journal is devoted to publishing cutting edge discovery, translational and clinical cancer research across the broad spectrum of oncology.

Ask the Editor – Inflammation, Metastasis, Cancer Microenvironment and Tumour Immunology

Got a question for the editor about inflammation, metastasis, or tumour immunology? Ask it here!

Continue reading announcement

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in