The extraordinary diversity of the world's mammals and birds

Published in Ecology & Evolution

“The richness of form and function in the natural world is undoubtedly part of its fascination; this intriguing variety is often the lure that draws one to the formal study of biology.”

T. R. E. Southwood (1988)

The extraordinary variation across the ecological strategies of mammals and birds certainly lured me into this study. For instance, some large herbivores live for decades (e.g., African elephant), while other small herbivores live fast and die young (e.g. mice, voles, agoutis). Hummingbirds show incredible adaptations to flight (they are the only birds that can fly backwards!) to enable them to extract nectar from flowers, whereas the flightless Common ostrich uses size, speed and strength to survive the African savannas. Predators, such as lions, cooperate and hunt in packs. Primates often spend the majority of their life in the treetops (e.g., guereza colobus). There is incredible diversity!

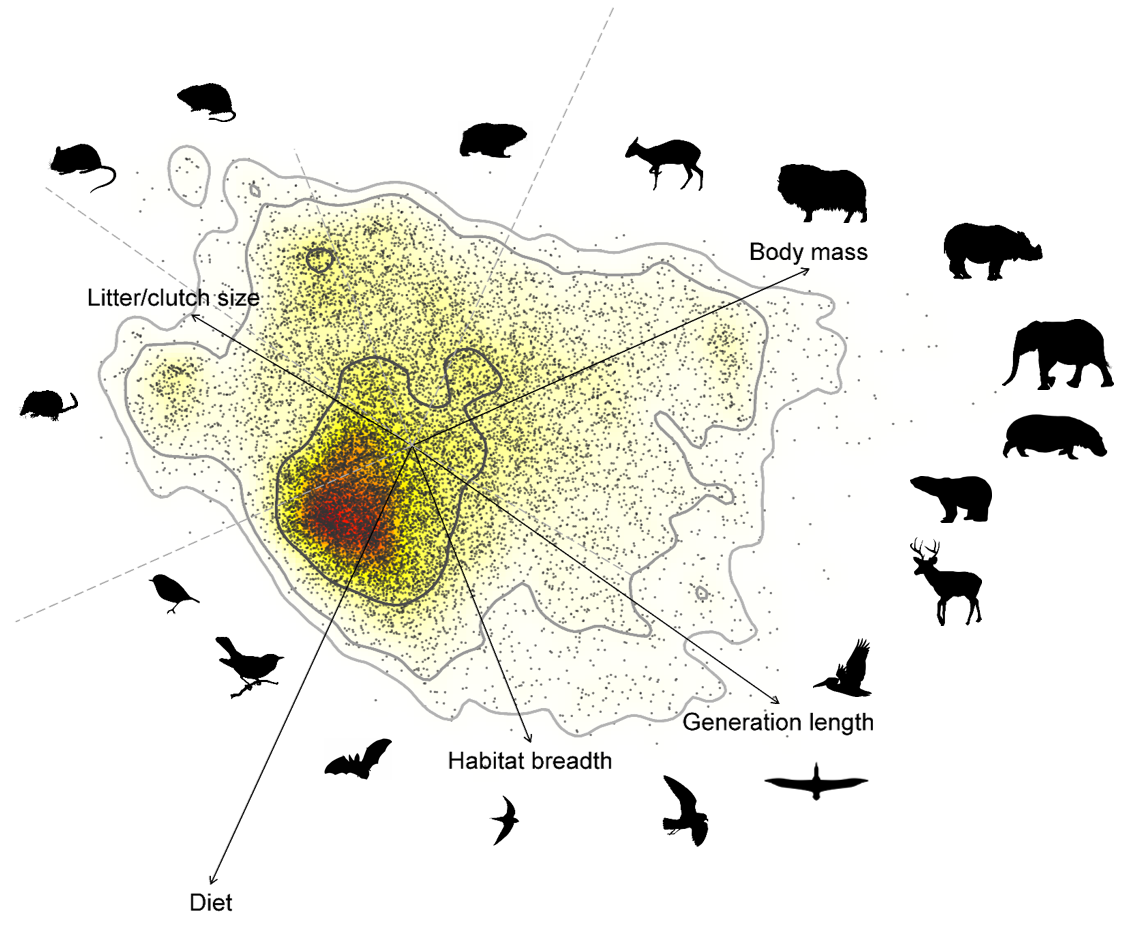

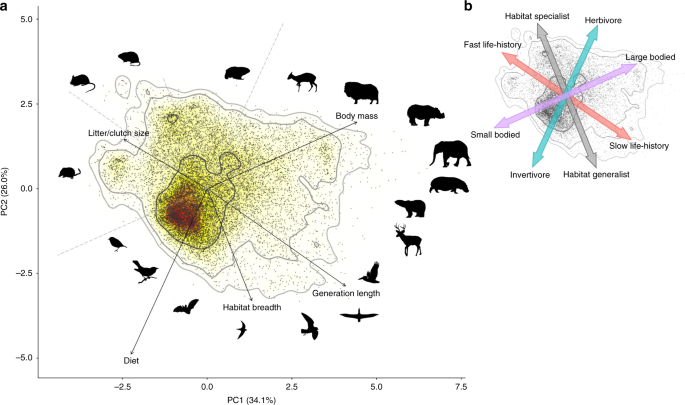

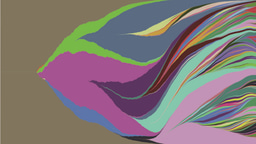

Yet, in our new article (published in Nature Communications) we distill this diversity down to two major ecological strategy axes. The first combines life-history (fast-slow) and body mass (small-large), and the second integrates diet (invertivore-herbivore) and habitat breadth (generalist-specialist). Together these form what we’ve termed the ecological strategy surface (or the fried egg diagram!).

To undertake this project two things came together, we had recently built a combined database of trait data for all mammals and birds of the world, from multiple sources (which was no mean feat!) and Sandra Diaz and colleagues published a brilliant paper on the ‘global spectrum of plant form and function’, which gave us a framework to apply to mammals and birds. This gave us the data and the tools to reveal patterns across ecological strategies. For example, by combining both mammals and birds we could look at how these species groups shared multidimensional ecological strategy space. Finding that mammals and birds overlap across only 31% of the combined strategy space. Instead, birds occupy 19% unique space and mammals 51% unique space.

Understanding the diversity of mammals and birds also peaked my natural history interest. For example, did you know that Andean Condor are the world’s largest flying bird at 10.87 kg, or that giraffe are the 9th heaviest land animal in the world (see table), or that the Light-mantled Albatross has the longest generation length at 44 years.

The top 10 heaviest land animals in the world

| Common name | Scientific name | Average body mass (kg) | IUCN status* |

| African elephant | Loxodonta africana | 3940 | VU |

| Asian elephant | Elephas maximus | 3220 | EN |

| White rhinoceros | Ceratotherium simum | 2286 | NT |

| Javan rhinoceros | Rhinoceros sondaicus | 1750 | CR |

| Indian rhinoceros | Rhinoceros unicornis | 1602 | VU |

| Hippopotamus | Hippopotamus amphibius | 1536 | VU |

| Sumatran rhinoceros | Dicerorhinus sumatrensis | 1260 | CR |

| Black rhinoceros | Diceros bicornis | 996 | CR |

| Giraffe | Giraffa camelopardalis | 900 | VU |

| Gaur | Bos gaurus | 800 | VU |

*NT = Near Threatened, VU = Vulnerable, EN = Endangered, CR = Critically Endangered

We also decided to look at the most pressing issue in all of the natural sciences - extinction. The recent IPBES report has outlined that around 25% of IUCN assessed species are threatened with extinction. In addition, extinction is already happening. Even just since 2015, when I first built the trait database, four species have been confirmed as globally extinct: Guam Reed-warbler (last seen 1969), Bramble Cay melomys (last seen 2009 - believed to be the first mammal to have been driven extinct by man-made climate change), Christmas Island pipistrelle (last seen 2009) and Bridled White-eye (last seen 1983).

However, not all species are equal. Some are more irreplaceable than others. Therefore, although the number of species going extinct is important, we believe that it will actually be the selective loss of specific ecological roles, and in turn ecological processes, which will have the greatest consequences around the world. Here, we shine a spotlight on these potential ecological consequences. For instance, we predict over double the loss of ecological diversity over the next 100 years than expected at random, shifting the mammal and bird species pool towards small, fast-lived, highly fertile, insect-eating, generalists.

Yet these projected extinctions have not yet happened - we still have time. Through habitat restoration and conservation management we still have the chance to protect the remarkable diversity of mammals and birds on Earth.

Follow the Topic

-

Nature Communications

An open access, multidisciplinary journal dedicated to publishing high-quality research in all areas of the biological, health, physical, chemical and Earth sciences.

Related Collections

With Collections, you can get published faster and increase your visibility.

Women's Health

Publishing Model: Hybrid

Deadline: Ongoing

Advances in neurodegenerative diseases

Publishing Model: Hybrid

Deadline: Mar 24, 2026

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in