The forensics of mobile mRNA data in plants

Published in Protocols & Methods, Cell & Molecular Biology, and Plant Science

It started as a small bioinformatics task to identify mobile mRNA in transcriptomic data in order to have a really robust dataset for machine learning. This was a problem of combing through sequencing data, that had been harvested from the shoot of the plant and root of the plant, to find out similarities and differences between short sequenced fragments of 100 nucleotide bases. I was well-rehearsed in problem solving as I had already worked in many disciplines: I had a degree in pure mathematics, and have published papers also in communication theory, ancient DNA, genome assembly, population genomics, but not on mobile mRNA before. Thus, in order to learn about mobile mRNA, I plunged into the literature to find out about the biological significance of mRNA moving between different parts of the plant and sourced all the papers available. What immediately hit me was that the scientific literature on this topic was confusing. In Arabidopsis, 2006 mobile mRNAs were reported, while in Nicotiana/Arabidopsis only 138, in Tomato/Nicotiana 1163, in Cucumber/Watermelon 130, in Cuscuta/Arabidopsis 9518 and in wine cultivars 2679. The measures were not comparable, the methods, the plant species and pipelines different, but I was not afraid of technical challenges. This mystery required my full Sherlock Holmes skills to forensically analyse many papers and their data again, to find a logically consistent explanation for why these numbers were so different.

Investigation

My training doing a DPhil in pure mathematics taught me to read every single line of each academic paper, whether it was my own or someone else's. The argument needs all the logical steps to be absolutely correct for the proof to work, and to a certain extent the same is true for bioinformatics pipelines, they are based on logic. Thus, I went and downloaded all the available data from the published papers, both the supplementary tables but also the gigabytes and gigabytes of raw sequencing data that had been deposited in public archives. Not all was available in sequencing archives, and some of it was corrupt, so I did not have a full dataset, but thankfully large enough to start seeing patterns. For the FAIR principles of science it is important to put the data in the archives to allow researchers to re-evaluate it again in light of advances in science. It turned out that the availability of the data was crucial for the findings.

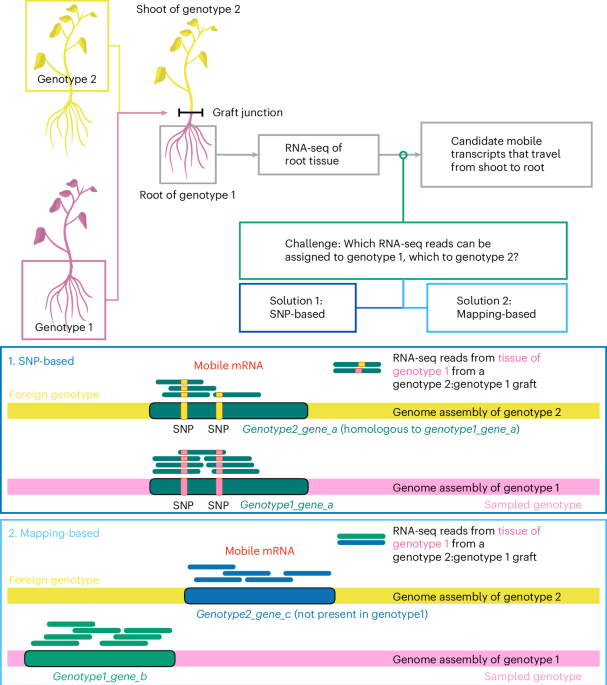

These sequences were short fragments consisting of nucleotides A,T,G,C, called bases, usually only 100 bases long, and there were millions and millions of these short sequences. And based on these, one should be able to infer which sequences were native to the root and which had moved from the shoot to root and were mobile fragments. Sometimes the difference between a mobile and non-mobile sequence would be a single base, say instead of C there would be a G. The samples were sequenced using an Illumina machine that has reliably produced accurate sequencing data for two decades now. The probability that any given base is wrong is very small, only 0.1%. However, given that these technologies can produce billions of base calls per experiment, this error rate, however, translates to millions of errors. If there are 10 000 reads on a transcript in one particular position, then 10 of them will be wrong due to sequencing errors. Some of the original papers had an absolute cutoff of 2 reads with the alternate base to call a mRNA mobile, so it started to look like that some of the mobile mRNA assignment had been noise. My colleagues Melissa Tomkins, Franziska Hoerbst and Richard Morris, had already done an excellent job in developing a Bayesian statistical framework for robust analysis of errors [1] that turned out to be a very useful method to re-analyse the data from the archives.

Lots of questions

Apart from the technical aspect of noise, I got very curious about the whole pipeline that the plants had been subjected to. Because of my work in ancient human DNA, I knew how difficult it was to avoid contamination. People assured me that RNA does not survive outside the plant for very long, but I was worried about pollen, the instruments and the whole methodology. The amount of sequencing is so massive that any little irregularity may be visible in the data, and I needed to know. I am a very curious person. I started to ask lots of questions from the lab side, things that are not always mentioned in the methods. Do you put a sheet between the root and the shoot? Do you cut the plants with the same blade, do you cut first the root and then the shoot? Which order different tissues are handled, are all the five tissues from the same plants or different plants? Were the samples from a single plant or where they pooled? It would make sense to pool the samples if there was a consistent but weak signal but if there was an intermittent signal, pooling would dilute it. Are they handled by different people? What is the developmental age of the plant? Are the RNA samples sequenced on the same lane? Was there any possibility that the plants would have been accidentally crossed in the greenhouse or growth chamber several generations ago? There was a small amount of heterozygosity in plants that should have been homozygous. Some of the questions were obviously strange and borderline insulting for the lab based scientists, but some were things that no-one could remember or had no reason to remember, as to which was cut first, the root or the shoot sample. If there was a contamination, this could indicate the direction of contamination, and could be visible in the sequencing data. Most of the questions were dead ends, but I could at least know that I had taken that alley, and was impressed by the carefulness of the lab based scientists. I was getting more and more obsessed into with the conundrum of mobile mRNA and wanted to get to the bottom of the problem and somehow unify in my mind the different results from different plants and labs.

In the end, there was no such revelation, but a growing understanding that all the papers had small problems, tiny parts of the data analysis that were overlooked, and would never have been caught in the 14-day turn-a-round time refereeing process typically allows. For instance, there was possible contamination, but because there was a cut-off at 10 000 reads on one pipeline, one missed the really highly expressed genes, that had 100 000 reads at any position, causing the very, very low level of contamination not to be visible in the original analysis. When all the data was plotted reciprocally, having changed this single parameter, a strong linear correlation appeared, and it became quite a plausible explanation for the data.

The inherent properties of genomes

There was also an explanation for the apparent small levels of heterozygosity. Genomes evolve all the time and there are different ecotypes, that have evolved naturally. One type of genome evolution is gene duplications, and I had encountered these in population genomics studies. These are very difficult to see from short read sequencing and can look like heterozygosity in an otherwise homozygous background. Indeed, it is estimated that in Arabidopsis alone, 200-800 genes out of the 27 000 genes are duplicated differently between ecotypes. Thus there are some genes that may have been mistakenly classified as mobile mRNA when assemblies of both ecotypes are not available. And indeed, the re-analysis of the data using the Bayesian framework had highlighted some transcripts that were consistently seen showing signals of mobility, while having a closer look, a number of these genes had been identified as putative duplicates in other studies and also careful inspection of the re-analysed data suggested the same.

Many parallel explanations

What we found out was that there were many different alternative explanations for the patterns in the data, that were earlier interpreted to be mobile mRNA. In one experiment there were both potential contamination (or mass flow of mRNA) and sequencing noise, as well as gene duplications that may have gone unnoticed. In another, the genome assemblies were incomplete. The only explanation that explained the different results of the papers in the literature was that mobile mRNA cannot easily be detected using large scale transcriptome sequencing approaches. I was tempted to say mobile mRNA does not exist, quod erat demonstrandum [2], but of course this is not mathematics, this is life sciences, so I am keeping my mind open and if there are other methods that show that mRNA is indeed selectively and specifically mobile and these are shown in different species, and contexts, I am happy to update my knowledge to the newest evidence. This is how science works, and it is great to be part of this scientific process. This project was a great collaboration between three different labs with expertise on different areas and it was crucial to learn so much from all of them. I want to thank all the collaborators, for exciting discussions, encouragement and challenges, especially Melissa Tomkins and Franziska Hoerbst for the close and fun collaboration and Richard Morris for letting and encouraging me go far beyond the original aim of the little bioinformatics task.

[1] Tomkins M, Hoerbst F, Gupta S, Apelt F, Kehr J, Kragler F, Morris RJ. Exact Bayesian inference for the detection of graft-mobile transcripts from sequencing data. J R Soc Interface. 2022 Dec;19(197):20220644. doi: 10.1098/rsif.2022.0644. Epub 2022 Dec 14. PMID: 36514890; PMCID: PMC9748499

[2] Which was to be demonstrated, a traditional way to finish mathematics proofs.

Follow the Topic

-

Nature Plants

An online-only, monthly journal publishing the best research on plants — from their evolution, development, metabolism and environmental interactions to their societal significance.

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in