The Poisoned Chalice: Is Our Passion for Remote Work Negatively Impacting Our Mental Health?

Published in Social Sciences

Where the notion of working from home (WFH) was simply not an option for workers, the health crisis forced the rapid acceleration of digital transformation towards remote offices. While WFH was and is favoured by the majority of employees, there’s mounting evidence that it can be detrimental to their health.

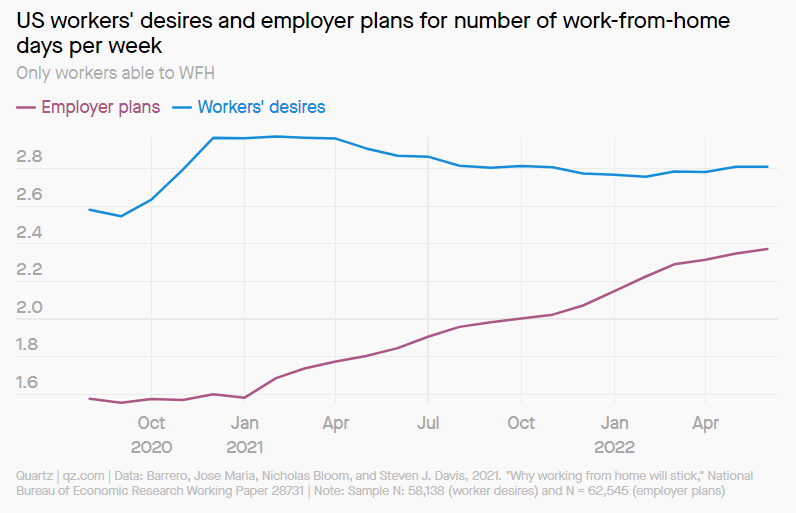

Fig 1. Above, we can see data published by Quartz and shared in the World Economic Forum which highlights the extent in which worker desire to work from home has consistently outpaced employer plans to deliver a WFH infrastructure during and beyond the pandemic.1

The motivations for employees to operate from home are clear. According to the US Census Bureau, the typical daily commute time in the United States is around 54 minutes, with some cities like Chicago experiencing average commuting times of 70 minutes.2 This can be a stressful and fatigue-inducing daily staple that’s instantly removed through WFH.

In saving time on commuting, workers have the freedom to either unwind, or fill their days with more productive and healthy pastimes, such as going to the gym, or simply unwinding before and after work.

Acting to minimise commute times is supported by the National Alliance on Mental Illness, which confirmed that setting up a morning routine that avoids rushing out the door each day is essential to worker wellbeing.3

Crucially, the lure of WFH also transcends personality types. According to a survey from Myers-Briggs Co., both individuals categorised as introverts and extroverts sought to work from home on a more hybrid basis. Despite their reputation as socially-oriented employees, 82% of extroverts surveyed stated that they preferred to work on a more hybrid basis.4

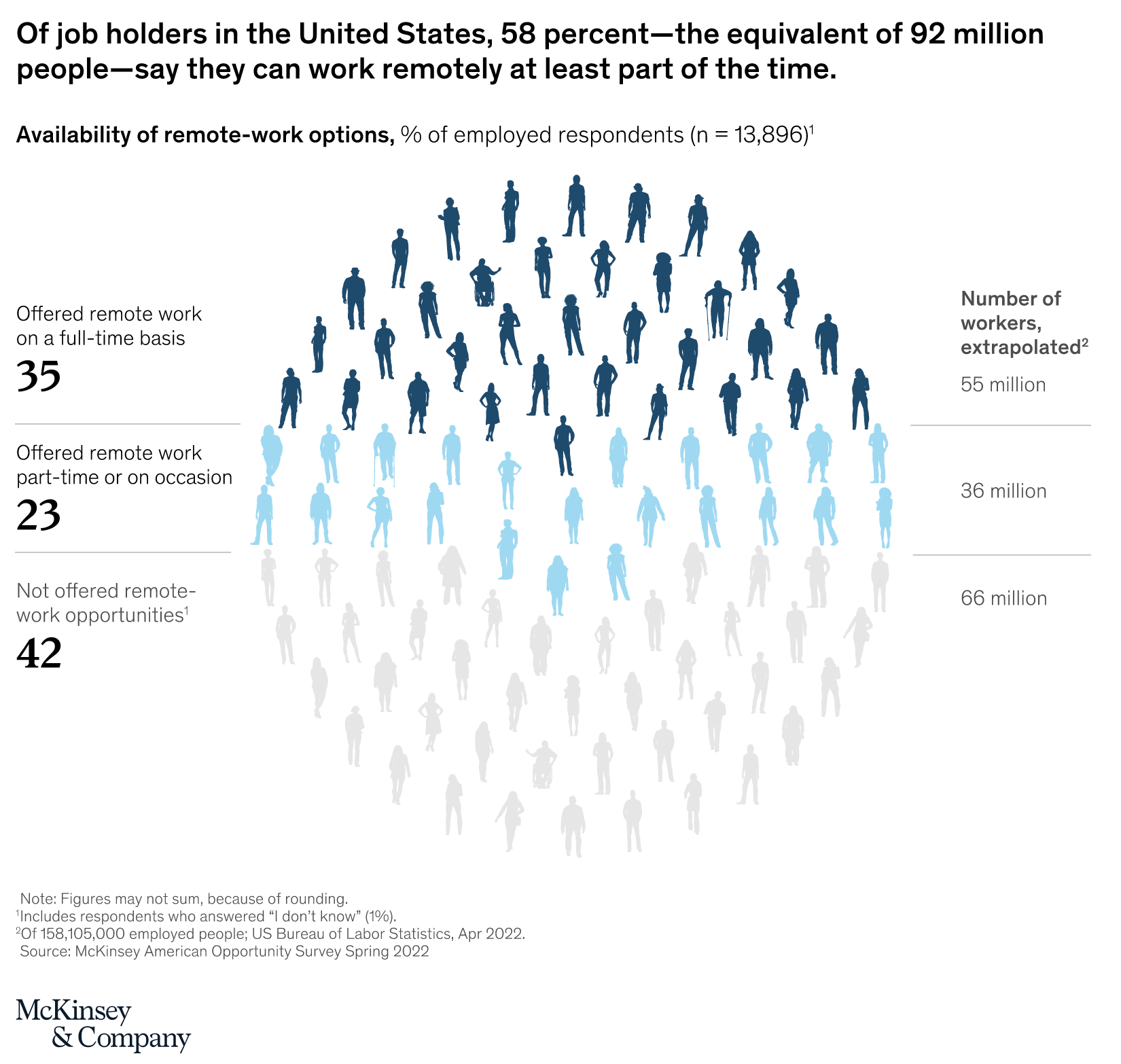

Fig 2. As highlighted in Fig1, employers are continuing to build new measures to accommodate WFH. In the above chart from McKinsey & Company, we can see the extent in which employees have been offered the opportunity to work on a remote basis. With 58% of employees, the equivalent to 92 million workers, having the ability to work remotely at least part of the time, it’s essential that more knowledge is gathered about the effects of such a fundamental shift in daily life.5

Measuring the Impact of WFH

There’s little doubt that the rise of working from home in the wake of the pandemic has been largely well-received among employees throughout the world, but evidence has been mounting that the impact of remote work carries significant and adverse ramifications for employee mental health.

Research conducted in the early stages of the pandemic saw that employees in Pakistan shifed hastily towards obligatory, high-intensity telework carried both a quantitative impact on employee wages and working hours, as well as a subjective impact on job satisfaction, motivation, perceived career prospects, physical, and mental health.6

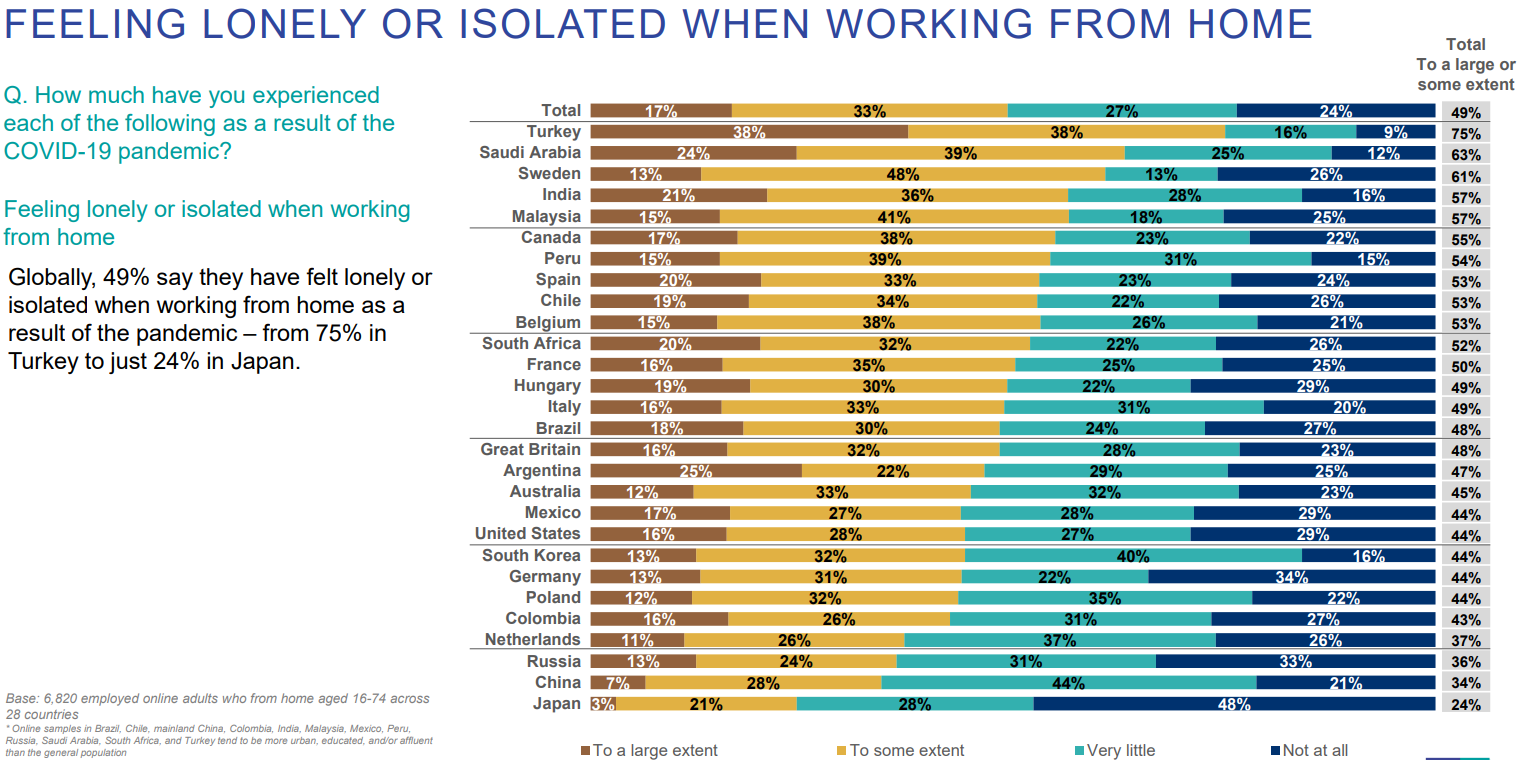

Fig 3. As the data above from the World Economic Forum shows, approximately 49% of employees on a global scale have reported feeling lonely or isolated working from home in the wake of the pandemic.7 These figures can differ significantly based on geographic location, with 75% of employees in Turkey feeling isolated to a large or some extent, while more than 50% of workers in nations such as France, South Africa, Spain, Canada, Saudi Arabia, Chile, and India all experiencing similar feelings of loneliness.

During the midst of the pandemic, in a research article published in 2020, Jodi Oakman et al found that ten health outcomes were reported across 23 papers in the wake of the rise of WFH, including pain, self-reported health, safety, well-being, stress, depression, fatigue, quality of life, strain, and happiness.

The results found that women were less likely to experience improved health outcomes when working from home, though the impact of health outcomes were strongly influenced by the degree of organisational support to workers.8

In a more recent research paper, published in 2022, Katharine Platts et al found that detrimental health impacts of WFH employees during lockdown were most acutely experienced by those with existing mental health conditions regardless of factors like age, gender, or work status. These conditions were also found to be exacerbated by working regular overtime.

For respondents without mental health conditions, predictors of stress and depressive symptoms were being female, under 45 years of age, home-working part time and two dependents. However, men also reported greater levels of work-life conflict.

Furthermore, place and pattern of work carried a greater impact on women. Factors like lower leadership quality led to a greater likelihood for stress and burnout for both men and women, and for employees aged >45 years, carried a significant impact on the level of depressive symptoms experienced.9

The Threat of Burnout

Although it may initially seem counter-intuitive considering the level of time saved on commuting hours for WFH employees, the impact of burnout can carry a significant psychological burden on workers.

The threat of burnout has been addressed in remote workers prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, and a 2019 survey conducted by Digital Ocean found that 82% of remote tech workers in the US have felt burnt out, while 52% reported that they work longer hours than those in the office.

Significantly, 40% of remote employees surveyed claimed that they felt as though they needed to contribute more than their office-based counterparts.10

These figures from the pre-COVID-19 survey appear to be corroborated by post-pandemic findings, too. According to a Hays survey of 8,301 professionals, 52% of respondents reported working longer hours when working remotely than before the emergence of COVID-19.11

These increased levels of exposure to screens when WFH can lead to other complications that may impact the mental health of employees. Exposure can lead to factors like eye-strain and eye fatigue, and can cause workers to suffer from sleep disorders.12

Finding the Best of Both Worlds

Given the impact of WFH on the wellness of employees, the age of remote work may seem like a poisoned chalice, but evidence suggests that a more hybrid approach can cause workers to managed their happiness in a more sustainable fashion.

Furthermore, it seems that some CEOs are beginning to heed this sentiment. In February 2023, Amazon CEO Andy Jassy pushed forward with a return-to-work mandate that requires employees to be in the office at least three times a week.13

In their September 2021 Frontiers in Psychology paper, Akiyoshi Shimura et al found that from a two-wave panel survey of before and after the pandemic among 3,123 office workers throughout 23 tertiary industries, a more hybrid approach was likely to see the best results in terms of employee wellness.14

“This empirical study provides evidences that remote work decreases psychological and physical stress responses when controlling the confounding factors such as for job stressors, social support, and sleep status as personal intervening factors,” the findings suggested. “On the other hand, the effects of remote work on presenteeism were limited, although full-remote work was found to have a negative effect on presenteeism.”

As we continue to adapt to life in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic, it’s more likely that we’ll see industries refine their approaches to WFH. Although the rise of presenteeism may encourage more employers to look more favourably to adopting work from home models, the long-term impact on employee wellness could cause a widespread retrace into more hybrid working patterns.

Whether external factors surrounding productivity or cost-effectiveness will help or hinder a future of hybrid work, evidence suggests that a healthy office/home balance can be positive in managing the mental health of employees.

References

1 Cheng, M. (2022, July 26). Work from home: Firms are giving workers what they want. The World Economic Forum. Retrieved April 13, 2023, from https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2022/07/work-from-home-employers-workers-work-life

2 Census Bureau Estimates Show Average One-Way Travel Time to Work Rises to All-Time High. (2021, March 18). Census Bureau. Retrieved April 13, 2023, from https://www.census.gov/newsroom/press-releases/2021/one-way-travel-time-to-work-rises.html

3 Greenstein, L. (2017, August 9). The Power of a Morning Routine. NAMI. Retrieved April 13, 2023, from https://www.nami.org/blogs/nami-blog/august-2017/the-power-of-a-morning-routine

4 Steen, J. (2022, April 12). Study Shows 74 Percent of Introverts Don't Want Full-Time Remote Work. They Want This Instead. Inc. Magazine. Retrieved April 13, 2023, from https://www.inc.com/jeff-steen/study-shows-74-percent-of-introverts-dont-want-full-time-remote-work-they-want-this-instead.html

5 Is remote work effective: We finally have the data. (2022, June 23). McKinsey. Retrieved April 13, 2023, from https://www.mckinsey.com/industries/real-estate/our-insights/americans-are-embracing-flexible-work-and-they-want-more-of-it

6 Memon, M. A. (2022, December 21). Work-From-Home in the New Normal: A Phenomenological Inquiry into Employees' Mental Health. NCBI. Retrieved April 13, 2023, from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC9819185/

7 Charlton, E. (2021, January 4). This is how COVID-19 has impacted workers' lives around the world. The World Economic Forum. Retrieved April 13, 2023, from https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2021/01/covid-19-work-mental-health-world-economic-forum-ipsos-survey/

8 Weale, V., Oakman, J., Kinsman, N., & Graham, M. (2020, November 30). A rapid review of mental and physical health effects of working at home: how do we optimise health? - BMC Public Health. BMC Public Health. Retrieved April 13, 2023, from https://bmcpublichealth.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12889-020-09875-z

9 Platts, K. (2022, January 29). Enforced home-working under lockdown and its impact on employee wellbeing: a cross-sectional study - BMC Public Health. BMC Public Health. Retrieved April 13, 2023, from https://bmcpublichealth.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12889-022-12630-1

10 Swanner, N. (2019, July 23). Working From Home Doesn't Automatically Solve Burnout. Dice. Retrieved April 13, 2023, from https://www.dice.com/career-advice/burnout-remote-work-study

11 Churchill, F., & Urquhart, J. (2021). 99592. People Management. Retrieved April 13, 2023, from https://www.peoplemanagement.co.uk/article/1745150/half-professionals-working-longer-hours-at-home-poll-finds

12 Blue Light: Fact And Fiction. (2020, February 8). Vision Magazine. Retrieved April 13, 2023, from https://blog.eyeglasses.com/vision-magazine/blue-light/

13 Payton, L. T. (2023, February 28). What remote work does to your brain and body. Fortune. Retrieved April 13, 2023, from https://fortune.com/well/2023/02/28/what-remote-work-does-to-your-brain-and-body/

14 Ruhle, S. A., & Schmoll, R. (2021, August 27). Remote Work Decreases Psychological and Physical Stress Responses, but Full-Remote Work Increases Presenteeism. Frontiers. Retrieved April 13, 2023, from https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.730969/full

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in