Moving What Isn't There: The Illusion of Limb Movement

Published in Bioengineering & Biotechnology

This is because you used your internal senses in your body to do it. This is "proprioception" and is sometimes called the sixth sense.

Proprioception is more complex than the standard five as it is made up of different senses within and upon the body. This includes the activity of the muscles, if they are shortened or stretched, plus how the skin stretches as the limbs move. All these things come together to help form a model of the body that your central nervous system uses to work out how it is moving and what to do next. Proprioception is how you can touch your nose in the dark, or with your eyes shut.

People who use prosthetic limbs don't usually have any sense of where their prosthetic limbs are. Even sophisticated electronic prostheses do not measure their joint position and feed it back to the operator. When using a prosthetic limb the person has to infer the position of the limb from the way the weight of the prosthesis shifts as a joint flexes, or if they can see the joint move. Some ways to try to feed this information back to users have been tried in the past. For example, the joint position can be encoded as the gap between to points of contact on the arm, the smaller the angle the smaller the gap. People can learn to use this, if they are motivated. In general, a user of a prosthetic limb wants to get on with their lives and does not want the hassle of learning to use feedback systems, or apply the concentration needed to actually benefit from the information gained. Almost everyone else doesn't have to, so why should they? Implants that stimulate the nerves can supply useful proprioceptive information , but they are too expensive to be considered for routine prostheses. What is required is something light, cheap and low profile that is easy to use.

The good thing is that it is possible to manipulate the proprioceptive sense leading to an illusion of a movement. The Proprioception Illusion happens when a muscle is vibrated at the correct frequency. It causes the muscle spindles to fire. When this signal is received by the brain, it is interpreted that the muscle is stretching and so the limb must be moving, and that is what is felt. This sensation can be so powerful that exciting the elbow extensors when the nose is being held by the hand on the same arm cannot be reconciled and the brain makes us feel as if our nose is growing. This is called the Pinocchio Illusion. The illusion works on any muscle and so it is tempting to ask if if could work on an elbow that does not exist, or a prosthetic elbow worn on the body.

Ruth Leskovar and the team wanted to ask this question of persons whose limbs are different. That is, they either lost a part of their arm or were born with difference in their arm anatomy. This latter group are important and interesting. The do not "lack" a hand or an elbow, they are complete, just different. While those who have lost an elbow might be expected to feel the illusion, it was not clear if the second group would feel anything at all as they were not born with the joint to feel. No one had ever tried to answer this question before.

Through care and effort Ruth was able to recruit an impressive sixteen persons with limb differences, equal numbers of those who lost a hand and those who never had one. She was able to ask them to experience the vibration sensations. Her results showed that not everyone can feel the illusion of movement. When she worked with members of the staff and students at the university one member out of twenty five could not feel the illusion at all. When it came to the limb different participants fourteen felt something. Importantly, this included the people who were born without part of the limb. One person who did not have a conventionally formed elbow on either arm slowly came to realise what they were feeling was an elbow they never had. This asks important questions about how babies develop in the womb.

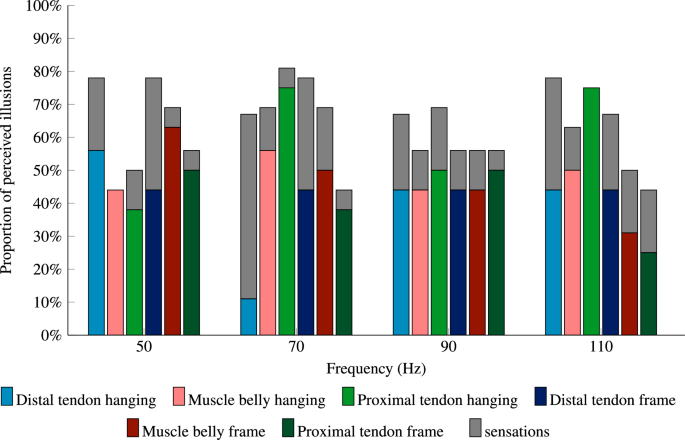

We tested three different locations to apply the vibration sensation: The tendon at the end of the muscle closest to the body (proximal tendon), the one furthest away (distal tenson) and the muscle belly. We tried four different frequencies (50, 70, 90 and 110Hz). We found that the best place for the vibrator was the tendon end closest to the body. This is important as the level where the limb difference starts is unique to every potential user and if we had to rely on the far end, many possible users would be excluded as their limb may not have a distal tendon. Equally important is that the way the vibrations are used, placed directly on the skin over the muscle, is the same as for the general population, which means we can do some of the next testing on other participants and not over-work our user volunteers.

Following the success of this work, there are many more questions to be answered, from the size of the vibrator to matching the precise frequency to the individual. This work has pioneered the investigation of an affordable way to feed limb position information back to a prosthetic user, which has many potential applications to improve the lives of those with limb difference.

This work is accepted for publication in Nature Scientific Reports.

The team: Ruth Leskovar1, Peter J. Kyberd2, Joseph M. Moore3, Timothy A. Exell3, and Chantel Ostler4

1 School of Energy and Electronic Engineering, University of Portsmouth, Portsmouth, UK.

2 Department of Ortho and MSK Science, University College London, UK.

3 Clinical Health and Rehabilitation Team (CHaRT), Centre for Integrated Health and Wellbeing, School of Psychology, Sport and Health Sciences, University of Portsmouth, Portsmouth, UK.

4 Portsmouth Enablement Centre, Portsmouth Hospitals University Trust, Portsmouth, UK.

Follow the Topic

-

Scientific Reports

An open access journal publishing original research from across all areas of the natural sciences, psychology, medicine and engineering.

Related Collections

With Collections, you can get published faster and increase your visibility.

Obesity

Publishing Model: Hybrid

Deadline: Apr 24, 2026

Reproductive Health

Publishing Model: Hybrid

Deadline: Mar 30, 2026

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in