Unveiling the Mystery of Vanadium: How High-Throughput Crystallography Cracked a Metallodrug Code

Published in Chemistry and Biomedical Research

Authors: Anne-Sophie Banneville, Rosanna Lucignano, Maddalena Paolillo, Virginia Cuomo, Marco Chino, Giarita Ferraro, Delia Picone, Eugenio Garribba, Irina Cornaciu-Hoffmann, Andrea Pica and Antonello Merlino

The "Iron Taxi" and its Mystery Passenger

In the crowded highway of the human bloodstream, proteins act as vehicles, transporting essential cargo to where it is needed most. One of the most important "taxis" in our plasma is Human Serum Transferrin. The protein consists of two lobes (N- and C-), both able to bind iron ions (Fe3+). Transferrin primary job is indeed to pick up and deliver them to cells, thanks to the help of the Transferrin Receptor, ensuring our body maintains the delicate balance of iron homeostasis.

However, Transferrin is not very selective. It often picks up "hitchhikers", other metal ions that mimic iron. One of the most intriguing hitchhikers is vanadium.

For decades, scientists have known that vanadium compounds hold incredible therapeutic potential, particularly for treating diabetes and cancer. We also knew that when these vanadium-based drugs enter the bloodstream, they bind to Transferrin. However, a major piece of the puzzle was missing. Despite years of research, no one had ever actually seen, at the atomic level, how a vanadium compound binds to Transferrin. The structural evidence was missing.

Until now.

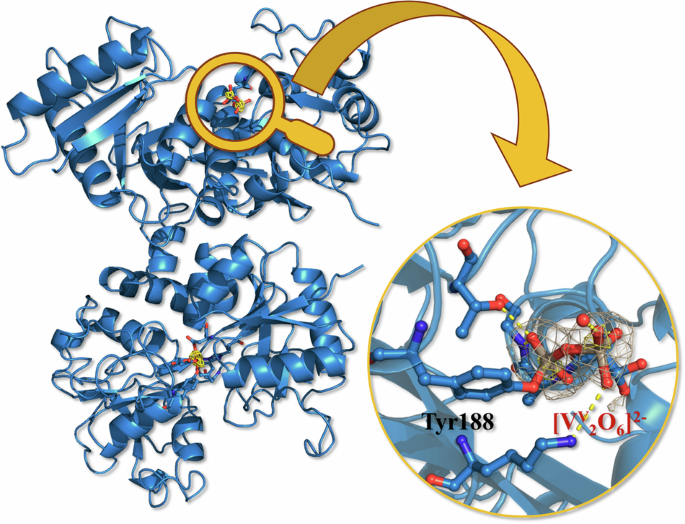

In our recent paper published in Communications Chemistry (First crystal structure of an adduct formed upon reaction of a vanadium compound with human serum transferrin | Communications Chemistry), we are proud to present the first X-ray crystal structure of an adduct formed when a vanadium compound reacts with human serum Transferrin.

A Synergistic Partnership: University of Naples Federico II meets ALPX

This discovery was not just an achievement of chemistry; it was also a culmination of friendship and collaboration. The project brought together the deep expertise in metallodrug/protein interaction from Prof. Antonello Merlino’s lab at the University of Naples Federico II and the advanced structural biology capabilities of ALPX, a structural biology CRO in Grenoble, France.

For the two key players, this project was more than just a joint venture; it was a much-anticipated reunion for Prof. Antonello Merlino and Dr. Andrea Pica, who had been colleagues in Naples over a decade ago. When they parted ways, and Dr. Pica joined ALPX, they promised to find a way to work together again. It took ten years to hit all the right notes in the heavy-metal lineup, but they finally got the "band back together" for this project. It was the perfect opportunity to combine their specialized skills: Antonello’s mastery of metal-protein interactions and Andrea’s expertise in high-throughput crystallography.

The challenge they faced was significant. Vanadium is a "shapeshifter" in solution: Vanadium compounds hydrolyze, break down, and change form depending on pH and concentration, and V can change its oxidation state. Capturing a stable crystal of a V-based drug/Transferrin adduct requires specific experimental conditions and rapid and massive screening.

Attempts to crystallize the adduct with the iron-free (apo) protein had initially failed. However, by leveraging ALPX’s ability to screen conditions rapidly and efficiently, we shifted our focus. We screened many crystals and eventually targeted a specific form of the protein: monoferric Transferrin (FeC-hTF), where iron is bound only to the C-lobe.

This approach paid off. We obtained beautiful protein crystals suitable for structural analysis. We subsequently soaked these crystals with a vanadium compound to characterize the binding modes.

Thanks to the ALPX advanced pipeline, we successfully collected high-resolution X-ray diffraction data, allowing us to finally visualize the atoms with clarity.

The Proof is in the Pudding

When we solved the structure, we found something unexpected.

Existing theories suggested that vanadium would bind as a simple ion, likely mimicking iron and causing the protein to snap shut. Instead, we found a divanadate species ([VV2O6]2-, i.e. a [VV2O7]4- ion where an oxygen of the V coordination sphere is replaced by an O from the protein). The ion covalently binds to a specific protein residue, Tyr188 in the N-lobe, that is also known for binding iron physiologically.

Perhaps the most fascinating finding was the "posture" of the protein. Usually, when Transferrin binds a metal (like iron), the lobe that binds the ion undergoes a significant conformational change (i.e. it passes from an “open” to a "close" conformation).

However, our structure revealed that when the vanadium cluster binds the protein, the N-lobe stays open. It refuses to snap shut. Despite this open shape and the presence of the bulky vanadium passenger, our experiments confirmed that the protein is still capable of being recognized by the Transferrin Receptor.

Why This Matters

Understanding how metallodrugs interact with transport proteins is critical for designing better medicines.

- Drug Delivery: We now know that Transferrin can carry vanadium compounds without losing its ability to bind its receptor, suggesting it can indeed act as a delivery system into cells.

- Stability: The protein stabilizes a specific form of vanadium (divanadate) that is usually minor in solution, protecting it from further chemical changes.

- Toxicity and Efficacy: By seeing exactly where the metal binds, we can better predict potential side effects or modify the drug to improve its journey to the target.

Looking Ahead

This work represents a steppingstone. It demonstrates that the combination of rational drug design and high-throughput structural screening can solve problems that have persisted for decades.

The collaboration between ALPX and the University of Naples Federico II has proven that when industry-standard efficiency meets academic expertise, and when old friends reunite in the name of science, they can shed light on the complex interplay between metals and proteins. We are excited to continue this work, screening more metallodrug candidates to release the hidden potential of medicinal inorganic chemistry.

Follow the Topic

-

Communications Chemistry

An open access journal from Nature Portfolio publishing high-quality research, reviews and commentary in all areas of the chemical sciences.

Related Collections

With Collections, you can get published faster and increase your visibility.

Experimental and computational methodology in structural biology

Publishing Model: Open Access

Deadline: Apr 30, 2026

Advances in Asymmetric Catalysis for Organic Chemistry

Publishing Model: Open Access

Deadline: Mar 31, 2026

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in