What is chikungunya?

Published in Microbiology and Zoology & Veterinary Science

Chikungunya viral disease (CHIKVD) has been hitting the news headlines in 2025 due to outbreaks across the world. In fact, according to the European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC) there have been approximately 240,000 cases of Chikungunya across 16 countries or territories between January to the end of July. Alas, there have been 90 CHIKVD-related deaths during the same period.

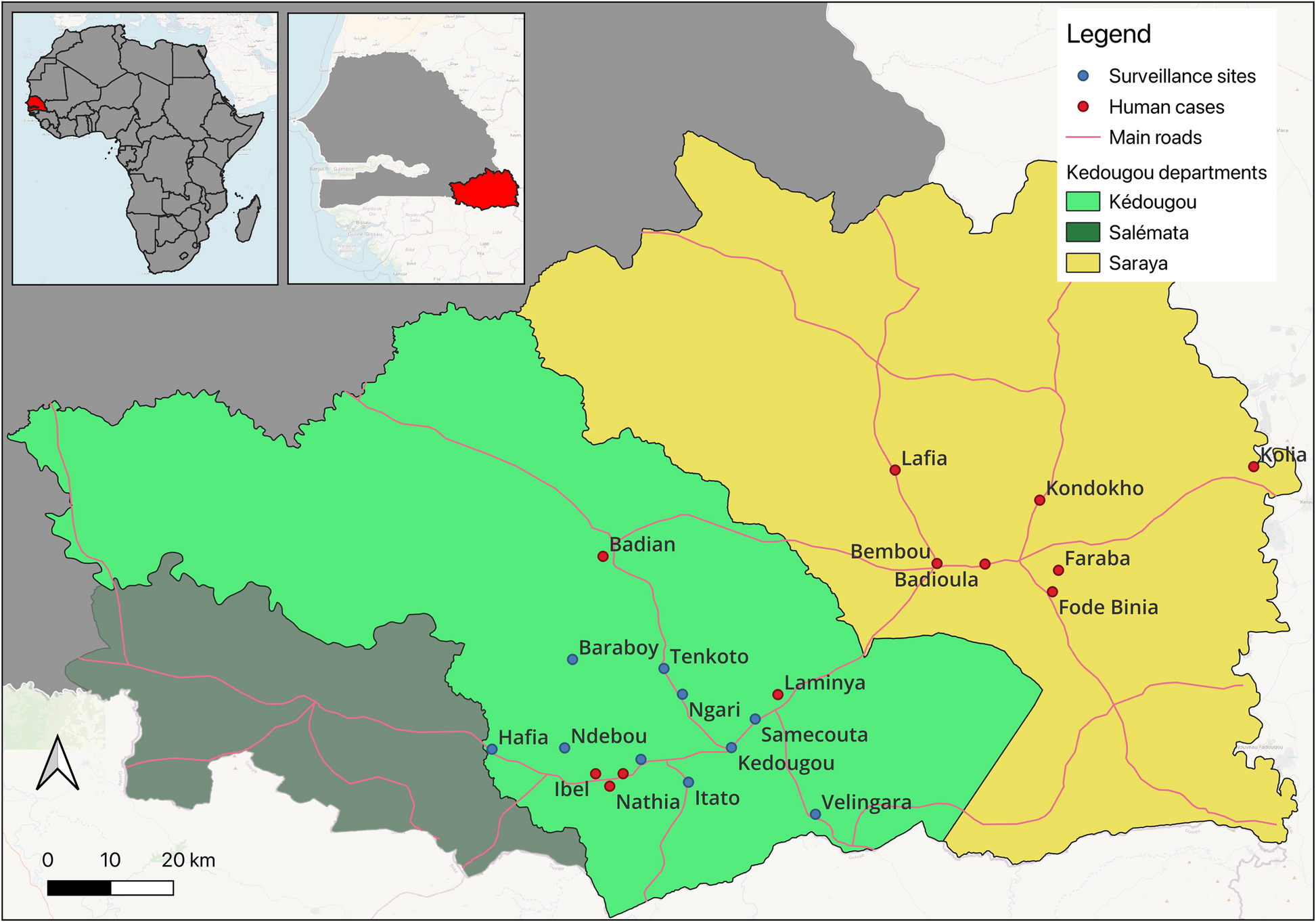

The disease is caused by the chikungunya virus and is transmitted from human to human by the mosquito (predominantly Aedes aegypti and Aedes albopictus) – incidentally, these are the same mosquitoes that are responsible for Zika and dengue transmission. A recent study by Alioune Gaye and colleagues, suggests that other Aedes mosquitoes - in particular Aedes Furcifer - should be monitored as they were found to be predominant in certain outbreak areas in the past few years.

The disease is caused by the chikungunya virus and is transmitted from human to human by the mosquito (predominantly Aedes aegypti and Aedes albopictus) – incidentally, these are the same mosquitoes that are responsible for Zika and dengue transmission. A recent study by Alioune Gaye and colleagues, suggests that other Aedes mosquitoes - in particular Aedes Furcifer - should be monitored as they were found to be predominant in certain outbreak areas in the past few years.

The chikungunya virus was first identified in 1952 in Tanzania and subsequently other countries in Africa and in Asia. Since 2004, chikungunya outbreaks have become more frequent due to the virus adapting and evolving, and the spread of the Aedes mosquito to regions where the population has not been exposed to the virus previously.

The virus is ingested by the mosquito when it feeds on an infected individual, it then replicates in the infected mosquito and enters its salivary glands. From there, the virus can be spread to another individual when the mosquito feeds again.

Disease symptoms in humans are similar to several other diseases such as dengue and malaria, so it can be easily misdiagnosed. Symptoms are characterised by sudden onset of fever, which is often accompanied by severe joint pain. The joint pain can be debilitating, and whilst this lasts for a few days in the majority of cases, in others, the pain can last for weeks, months or even years. Other common symptoms include joint swelling, muscle pain, headache, nausea, fatigue and rashes. Fortunately, most patients recover, but the disease can be severe in vulnerable individuals.

There are no specific antivirals for the disease and currently therapeutics are for the treatment of the symptoms – such as paracetamol for pain relief. However, there are two vaccines that have been given regulatory approval.

The most effective way of controlling the transmission of the virus and containing the outbreaks that we have seen is by controlling the vector. This seems to be the main strategy that the countries affected by recent outbreaks are adopting. Other countries, such as the UK, are advising their citizens to get vaccinations before travelling to affected regions.

Whilst CHIKVD is usually non-fatal, the increase in cases, especially in 2025 but also since 2004, have raised serious concerns amongst health officials, governments and regional disease control organisations. Going forwards, monitoring the situation and taking control measures seems to the best strategy available, but new insights from research into the virus and vector can only help to better control this disease.

Poster image: Image by Ajay kumar Singh from Pixabay

Follow the Topic

-

BugBitten

A blog for the parasitology and vector biology community.

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in