Why dietary restriction may not starve cancer, but still matters

Dietary interventions in cancer are often motivated by a simple idea: if tumor growth depends on nutrients, then reducing nutrient availability should limit cancer progression. This logic has driven interest in calorie restriction, carbohydrate restriction, fasting, and ketogenic diets across both preclinical and clinical settings. A recent review article in Communications Biology examines why this expectation is largely incorrect, and why dietary interventions may nonetheless remain biologically and clinically relevant.

A common assumption is that systemic nutrient restriction can deprive tumors of key metabolic substrates such as glucose, amino acids, or lipids. However, tumors do not rely on a single nutrient stream, nor do they passively absorb circulating nutrients. Extensive evidence shows that cancer cells are capable of catabolic rewiring, enabling them to maintain metabolic function across a wide range of systemic conditions.

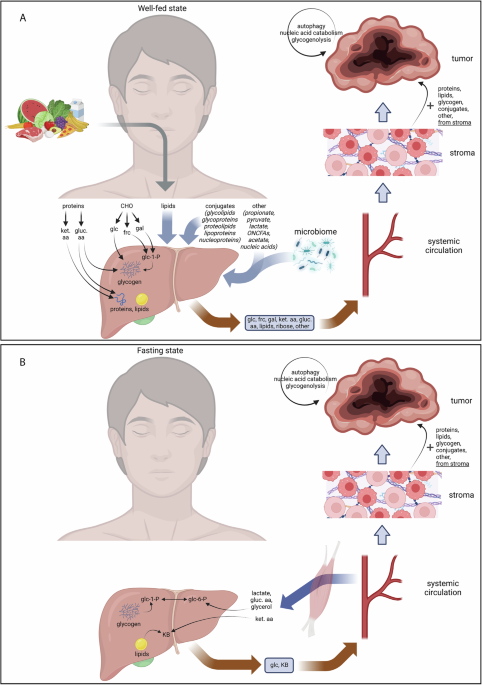

As summarized in the review, tumors can compensate for reduced dietary intake by shifting between substrates, increasing internal recycling of macromolecules, and exploiting metabolites supplied by host tissues. As a result, dietary restriction rarely produces sustained nutrient deprivation within tumors themselves.

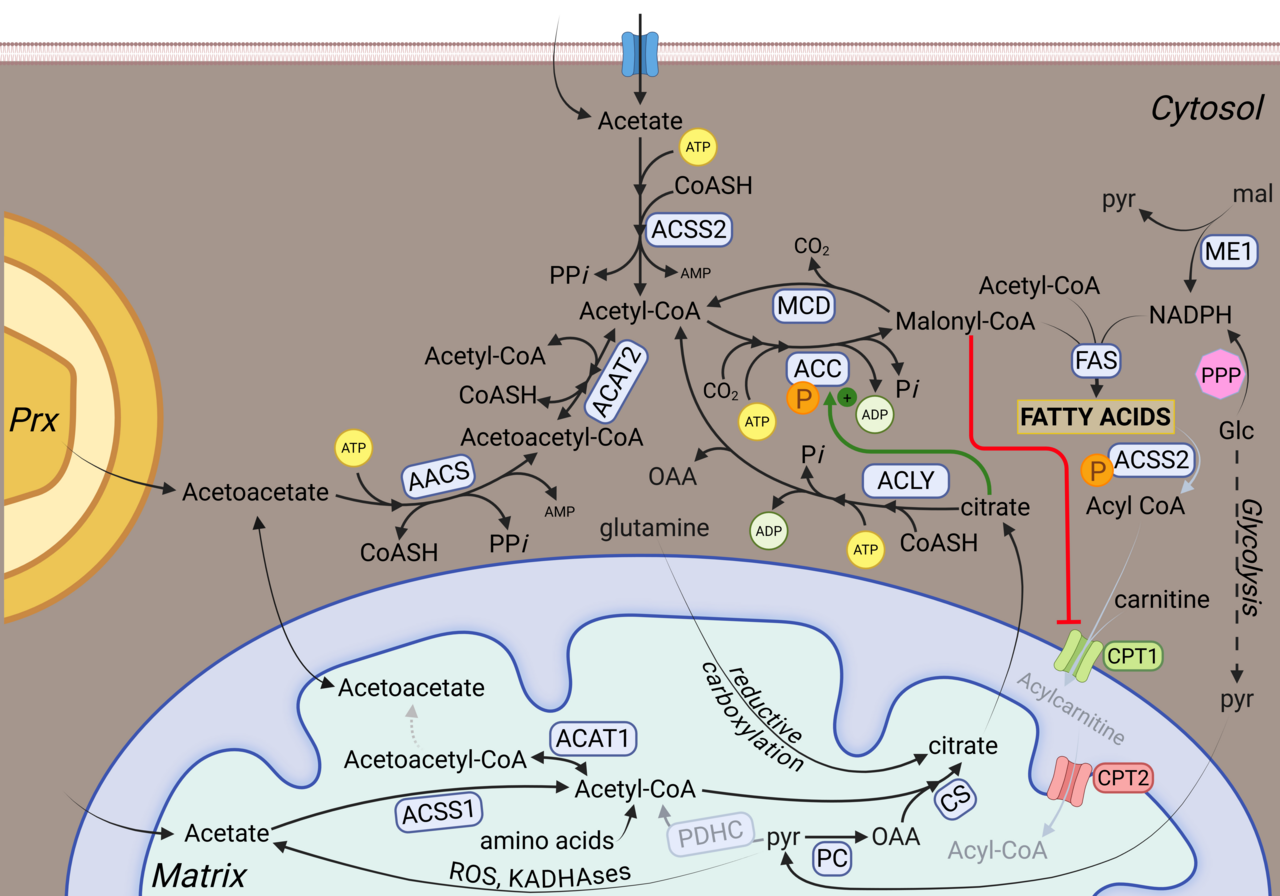

The review emphasizes that metabolic rewiring allows tumors to remain buffered against changes in diet. This buffering arises from several well-established features of cancer metabolism: Redundant catabolic pathways that enable switching between carbohydrates, fats, and amino acids, access to host-derived metabolites that are processed and redistributed by organs such as the liver, and intracellular recycling pathways that mobilize stored or structural components. Together, these mechanisms explain why reducing nutrient intake at the organismal level does not translate into effective metabolic starvation of cancer cells.

However, the failure of dietary interventions to starve tumors does not mean that diet is biologically irrelevant in cancer. Rather than acting through direct nutrient deprivation, diet primarily modulates the systemic host environment. By reshaping hormonal signaling, insulin dynamics, inflammatory and immune tone, and whole-body energy balance across organs, dietary interventions can indirectly influence tumor behavior, treatment tolerance, and therapeutic response, even when tumor-intrinsic access to nutrients remains intact.

By disentangling the misconception of tumor nutrient starvation from the genuine, indirect effects of diet, the review clarifies how dietary strategies should be evaluated in cancer research and care. Dietary interventions are best understood as adjunctive rather than curative, with expectations centered on host-mediated effects instead of tumor nutrient depletion. Integrating tumor metabolism with systemic physiology and therapeutic context helps explain the mixed outcomes reported in the literature and provides a more biologically realistic framework for applying diet in oncology.

Follow the Topic

-

Communications Biology

An open access journal from Nature Portfolio publishing high-quality research, reviews and commentary in all areas of the biological sciences, representing significant advances and bringing new biological insight to a specialized area of research.

Related Collections

With Collections, you can get published faster and increase your visibility.

From RNA Detection to Molecular Mechanisms

Publishing Model: Open Access

Deadline: May 05, 2026

Signalling Pathways of Innate Immunity

Publishing Model: Hybrid

Deadline: May 31, 2026

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in