Why We Need to Talk About the Criticism of the WHO During COVID-19

Published in Public Health, Arts & Humanities, and Law, Politics & International Studies

When COVID-19 swept across the globe, the World Health Organization (WHO) found itself under intense scrutiny. As the principal authority on global health, the WHO was expected to lead decisively. But instead of unified praise, it became the focus of intense criticism. From accusations of political bias to complaints about delayed action, the pandemic turned into a stress test not only for countries but also for international cooperation.

In our recently published study, we set out to make sense of this complex landscape of criticism. We asked a simple but essential question:

Why was the WHO so widely criticized, and what can we learn from it for the next global health crisis?

Looking for Patterns in the Chaos

To answer this question, we conducted a scoping review, a type of research that maps out what is already known about a topic. Unlike traditional reviews, it’s not about judging who is “right” or “wrong,” but about identifying themes and patterns across existing studies.

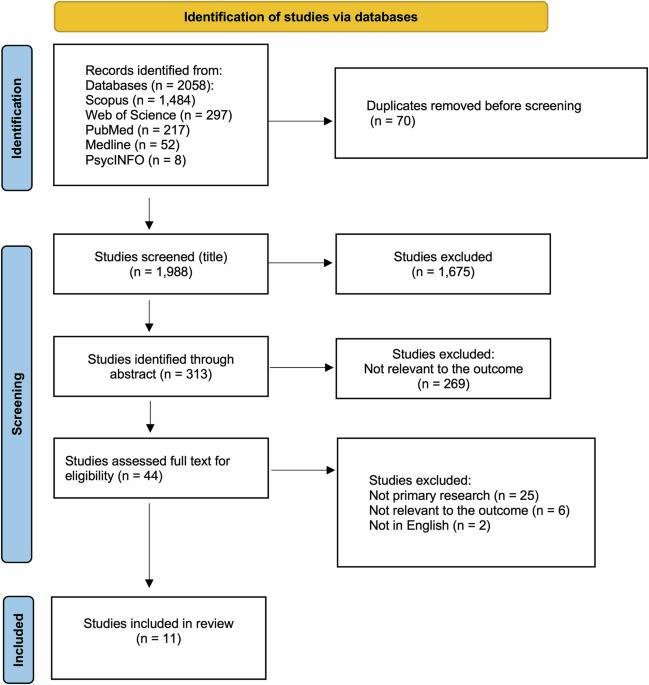

We combed through six major academic databases and screened over 2,000 studies. After applying clear criteria; peer-reviewed, English-language, focused on the WHO’s pandemic response, we narrowed this down to 11 high-quality studies published between 2021 and 2024.

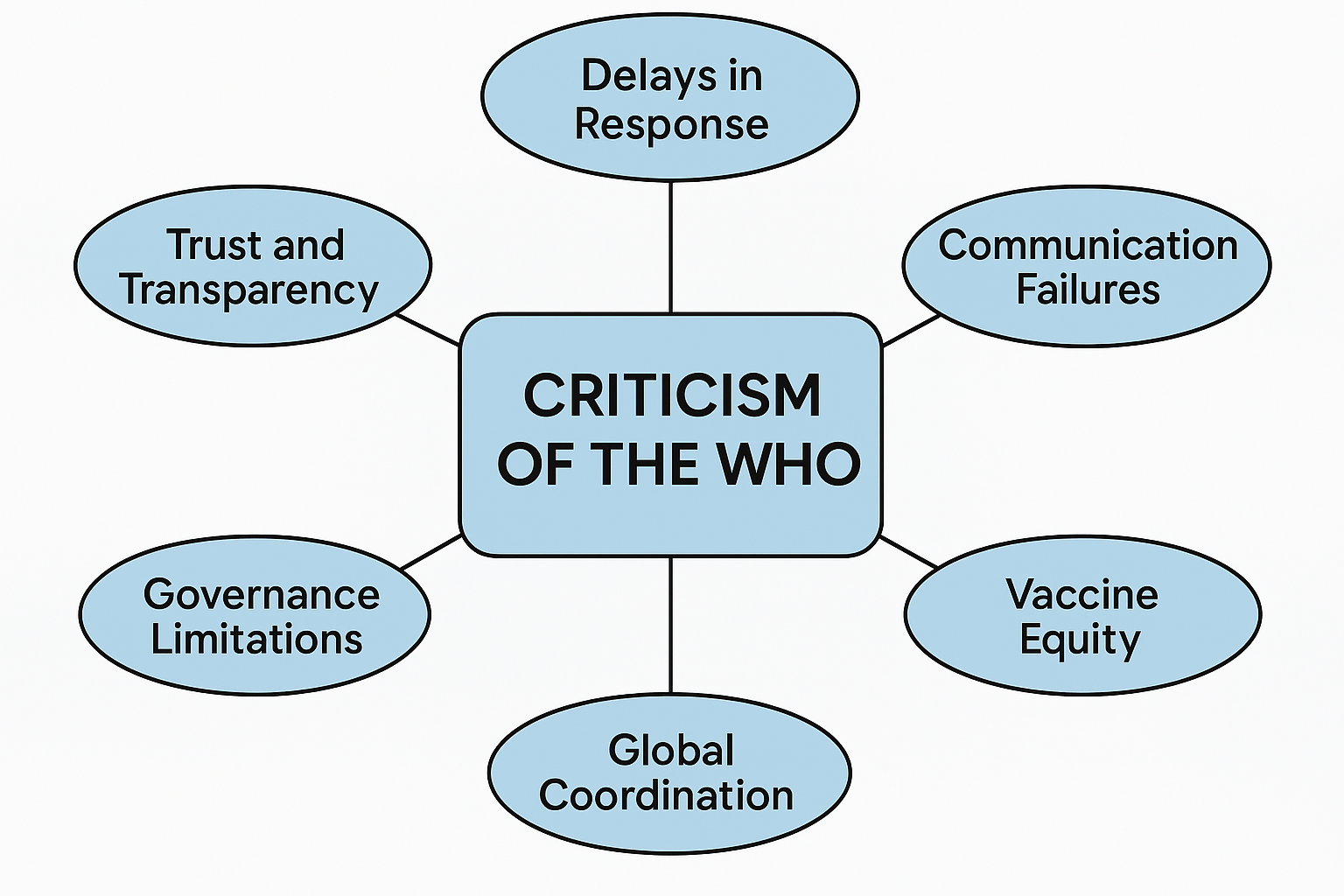

From these, we found six recurring themes in the criticism of the WHO:

What Went Wrong?

Let’s break these down:

1. Delays in Response

Many observers noted that the WHO was too slow to act. For instance, it waited until March 11, 2020, to declare COVID-19 a pandemic; weeks after cases had exploded in multiple countries. Critics argue this delay cost lives. But the WHO operates under international rules that limit its autonomy. It relies on data and cooperation from member states. In this case, that included early warnings from Taiwan that went unheeded, not necessarily due to incompetence, but because Taiwan is not a WHO member due to geopolitical tensions.

2. Communication Failures

Throughout the pandemic, people often received mixed messages: Should you wear a mask? Was airborne transmission a risk? Was the virus dangerous? The WHO, along with national governments, struggled to communicate clearly and consistently. This made room for misinformation to flourish; particularly on social media.

3. Vaccine Equity

The WHO helped launch COVAX, an initiative to ensure equitable global vaccine distribution. Yet many countries, particularly in the Global South, received vaccines too late or in too few numbers. Critics said WHO’s equity efforts were too slow and underfunded. Meanwhile, powerful countries engaged in “vaccine nationalism,” hoarding supplies or negotiating bilateral deals, sidelining multilateral solutions.

4. Global Coordination

The WHO is supposed to be the world’s health convener. But during COVID-19, new regional health partnerships and nationalistic strategies undermined this role. Some critics felt the WHO lacked teeth; offering advice rather than issuing enforceable rules. Others argued that WHO had no real tools to coordinate when countries didn’t want to cooperate.

5. Governance Limitations

Here’s a structural problem: the WHO gets most of its funding through voluntary contributions, many of which are earmarked for specific purposes by donor countries. This means powerful governments, often the same ones the WHO is meant to guide or critique, can influence its priorities. This dependence makes it hard for WHO to act independently, especially during politically charged crises.

6. Trust and Transparency

Trust in the WHO fell sharply in some parts of the world. In the United States, for instance, political polarization shaped how people viewed the organization; Democrats generally trusted it, while Republicans were skeptical. In Asia, Japan and South Korea had low approval ratings, while countries like the UK were more supportive. This uneven trust created a credibility gap at the very moment global alignment was most needed.

What Can Be Done?

We found that the criticisms weren’t just complaints; they were also calls for reform. The academic literature we reviewed offered concrete suggestions:

-

Improve communication strategies, especially on social media.

-

Increase funding and reduce political dependency on a handful of donor nations.

-

Incorporate regional actors, such as non-member entities like Taiwan, into decision-making and data-sharing frameworks.

-

Rebuild public trust by improving transparency and acknowledging past mistakes.

In short, many critiques saw the WHO not as an organization to be abandoned, but one that needs stronger tools and more independence to meet future crises.

A Political Blame Game?

One of the more striking patterns we uncovered is how criticism of the WHO often reflected deeper geopolitical tensions. Leaders like U.S. President Donald Trump used criticism of the WHO as a political tool, calling it "China-centric," eventually cutting U.S. funding and fully withdrawing the United States from the organization. Meanwhile, countries like China engaged in vaccine diplomacy to boost their global image. In this sense, the WHO became a stage on which nations acted out their rivalries, rather than a neutral ground for coordination.

This politicization wasn't new. The WHO had already faced similar blame during the 2009 H1N1 and 2014 Ebola outbreaks. But COVID-19 magnified everything. The stakes were higher, the platforms (especially digital media) more powerful, and public patience thinner.

Why This Matters

Global health doesn’t operate in a vacuum. It’s shaped by politics, ideology, funding structures, and public perception. Our review shows that unless these underlying issues are addressed, even the most well-intentioned global institutions will struggle.

The good news is that criticism can be constructive. By mapping and understanding the WHO’s challenges during COVID-19, we’re better positioned to strengthen global health governance for the future.

As new threats loom; whether climate-driven diseases, future pandemics, or biosecurity risks; international cooperation will be more important than ever. And that means building a WHO that’s trusted, transparent, and equipped to lead.

The present back and forth between WHO’s critics and defenders previews the coming tussle over how to repair global health governance and reform WHO in light of this disaster. The pillory and praise of WHO are worth exploring now so that the coming tsunami of demands for change do not destroy the organization in order to save it. David P. Fidler

We finalized this study at a moment of intense global scrutiny. Just as we submitted our manuscript, President Trump announced the U.S. withdrawal from the World Health Organization; a move that brought the political weight of the criticisms we had been analyzing into sharp focus. The timing was striking, but for us, this work is part of a broader effort to understand and improve global health governance. The publication marks a milestone, not a conclusion. We remain committed to exploring how governments and institutions like the WHO can respond more effectively and equitably in future crises.

Follow the Topic

-

Humanities and Social Sciences Communications

A fully open-access, online journal publishing peer-reviewed research from across—and between—all areas of the humanities, behavioral and social sciences.

Related Collections

With Collections, you can get published faster and increase your visibility.

Interdisciplinarity in theory and practice

Publishing Model: Open Access

Deadline: Dec 31, 2026

Addressing the impacts and risks of environmental, social and governance (ESG) practices towards sustainable development

Publishing Model: Open Access

Deadline: Mar 27, 2026

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in