Why We Wrote About Chronic Stress, Mitochondria, and Bioenergetic Debt

Published in Physics, Cell & Molecular Biology, and Paediatrics, Reproductive Medicine & Geriatrics

From Correlations to Constraints

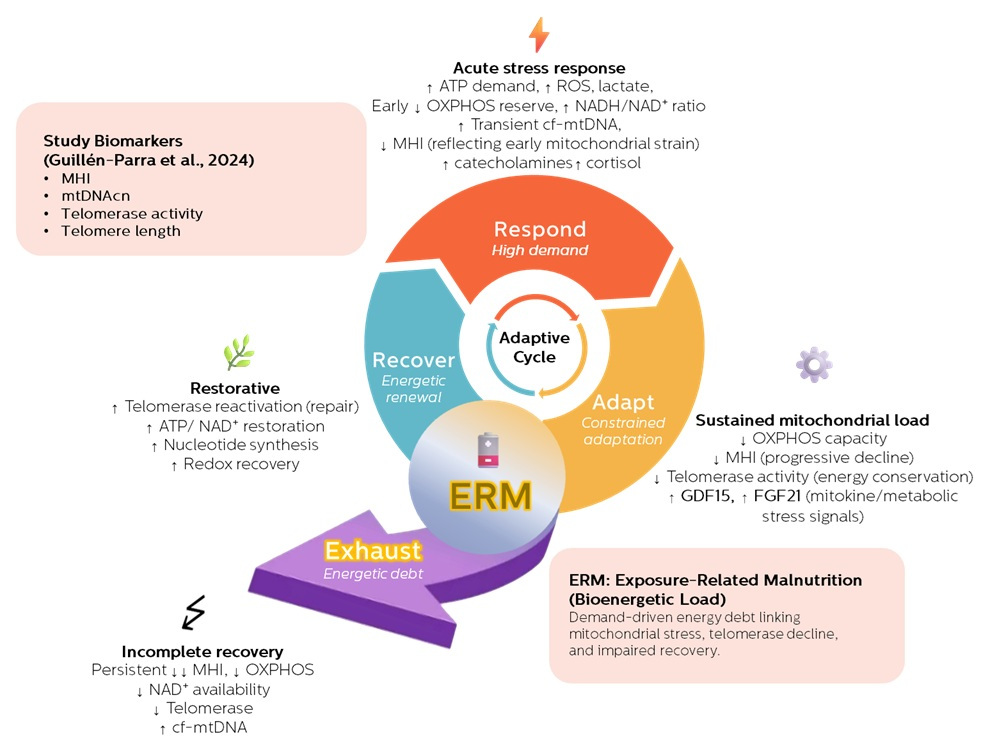

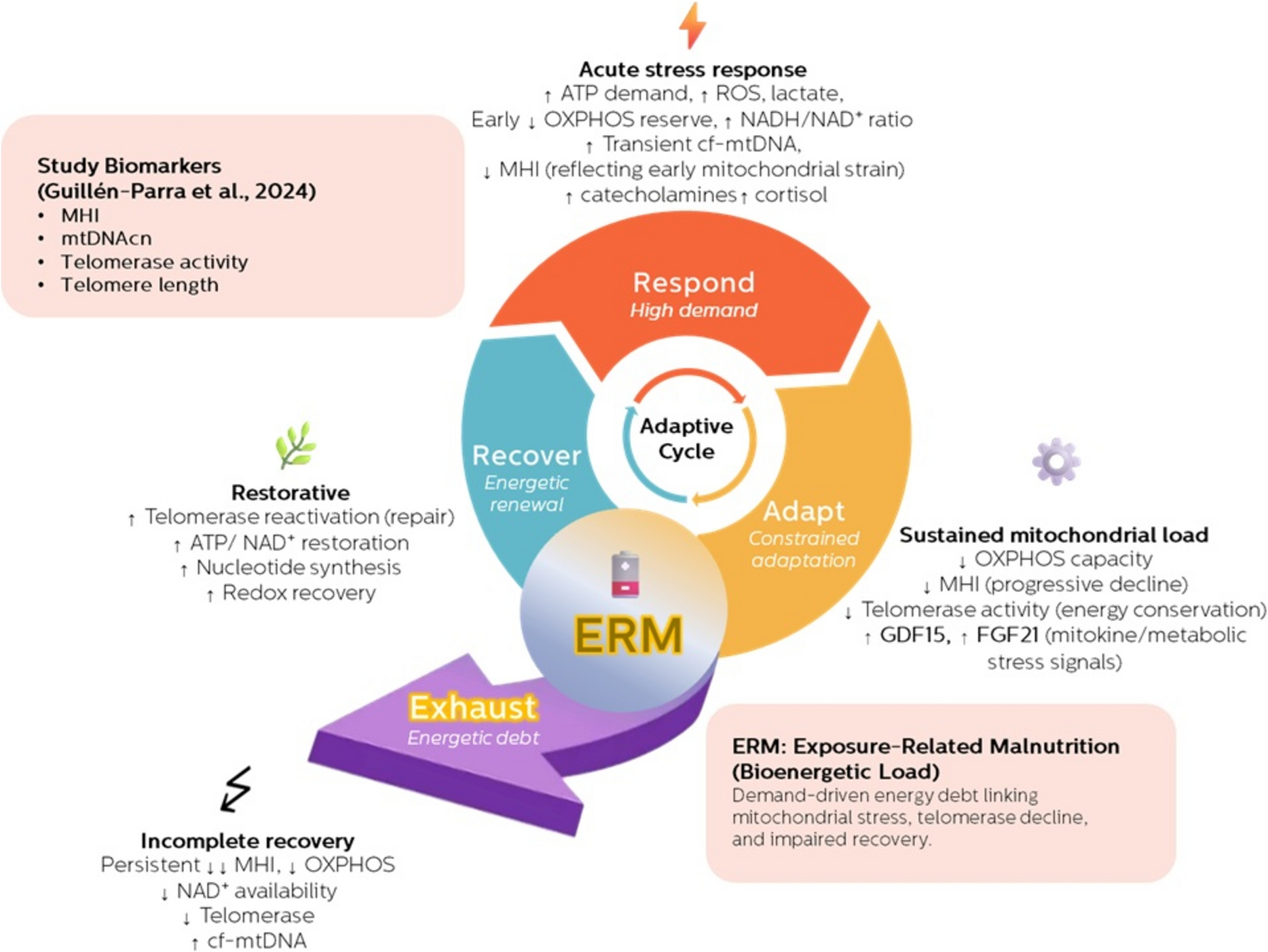

Much of the existing literature documents associations: stress correlates with mitochondrial dysfunction; telomere shortening correlates with aging; mitochondrial signals influence nuclear maintenance. What has been missing is a unifying explanation that connects these observations into a coherent biological logic—particularly one grounded in human longitudinal data, not just cellular or animal models.

The Guillén-Parra caregiver study offered a rare opportunity. It followed healthy individuals exposed to sustained psychosocial stress and showed that baseline mitochondrial energetic capacity predicted subsequent declines in telomerase activity, while telomere length remained largely unchanged over the short observation window. This temporal pattern was striking.

It suggested that aging-related changes may begin not with structural damage to DNA, but with early failure of energy-dependent maintenance processes.

Why Energy, Not Damage, Became Central

As we examined these findings more closely, it became increasingly difficult to interpret them using a traditional damage-accumulation framework. The participants were not malnourished, elderly, or clinically ill. Yet key systems responsible for long-term cellular maintenance were already being downregulated.

This led us to a different interpretation: the primary constraint was not the absence of substrates or excessive molecular injury, but limited energetic throughput—the capacity of mitochondria to convert available resources into usable energy for repair, renewal, and genomic maintenance.

From this perspective, telomerase activity emerged as a particularly informative marker. Unlike telomere length, which changes slowly, telomerase is dynamic, energy-dependent, and highly sensitive to redox state, NAD⁺ availability, and mitochondrial function. Its decline, therefore, may represent one of the earliest measurable signs that recovery capacity is being compromised.

ERM as a Missing Mechanistic Framework

This reasoning naturally aligned with the Exposure-Related Malnutrition (ERM) framework we have been developing. ERM conceptualizes chronic stress as a persistent energetic demand that repeatedly activates catabolic responses while limiting the resources needed for full anabolic recovery.

Crucially, ERM does not describe classic malnutrition. Calories may be sufficient—or excessive. What is lacking is functional energy availability for repair. Over time, incomplete Respond–Adapt–Recover cycles accumulate into what we describe as bioenergetic debt: a state in which maintenance processes are progressively deferred, not because they are unnecessary, but because they are energetically unaffordable.

Seen through this lens, the mitochondria–telomere axis observed in stressed humans becomes less mysterious. Mitochondrial insufficiency and telomerase suppression are not independent hallmarks of aging; they are coordinated outcomes of unresolved energetic strain.

Reframing Early Aging

One of our motivations in writing this review was to challenge a subtle but pervasive assumption in aging research—that early aging phenotypes inevitably reflect irreversible decline.

Instead, the human evidence we reviewed suggests something more hopeful and more actionable: early aging may represent a failure of resolution, not a terminal endpoint. Telomerase decline precedes telomere shortening; energetic strain precedes structural damage. These are signals, not conclusions.

This reframing has implications beyond theory. It suggests that recovery biology—circadian alignment, nutritional sufficiency, mitochondrial efficiency, and hormesis-informed stress exposure—deserves a more central role in both aging research and preventive medicine.

Looking Forward

We see this paper not as a final answer, but as a conceptual bridge. It connects stress physiology, mitochondrial energetics, telomere maintenance, and aging into a single, energy-dependent narrative grounded in human data.

Future work will need to move beyond static biomarkers toward dynamic measures of recovery capacity, integrating mitochondrial health indices, redox status, NAD⁺ metabolism, and emerging markers of energetic strain. Only then can we begin to map not just how fast we age, but why, when, and whether that trajectory can be altered.

Ultimately, we wrote this paper to argue for a shift in perspective:

that aging, at least in its early stages, may be less about damage already done—and more about repair that never quite gets the chance to happen.

https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10522-025-10377-x

Follow the Topic

-

Biogerontology

Biogerontology is a peer-reviewed journal dedicated to exploring the biological basis and mechanisms of ageing, with an aim of promoting healthy old age.

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in