World Hepatitis Day 2024: It's Time for Action

Published in Public Health

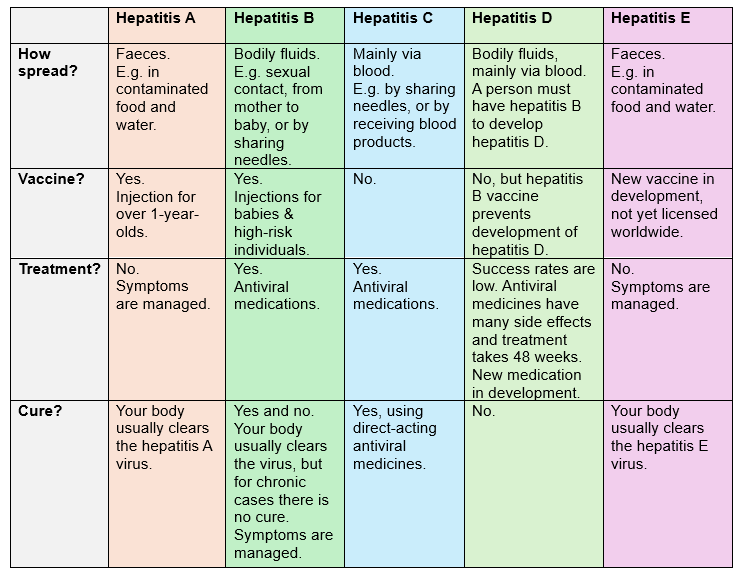

Hepatitis is inflammation of the liver, often as a result of a viral infection (hepatitis A, B, C, D and E). It is a major global disease, with over 2 million new cases and 1.3 million deaths per annum.[1] World Hepatitis Day focuses on increasing understanding of viral hepatitis and its consequences. If left untreated, some forms of hepatitis can cause chronic liver disease, which can lead to further complications including cirrhosis, liver cancer and liver failure. It is unlikely that the World Health Organisation’s (WHO) goal to combat hepatitis across the world by 2030 will be met unless drastic steps are taken, and the theme of this year’s World Hepatitis Day is “Take action. Test, treat, vaccinate”.

Research

Much research is being undertaken to determine the best ways to manage and treat hepatitis infections. Springer Nature publishes research on hepatitis that relates to the United Nation’s Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) which call for all countries to act to improve conditions for humanity and the planet. This hepatitis-related research supports SDG3 “Good Health and Wellbeing” and SDG10 “Reduced Inequalities” in particular. The articles promote WHO’s SDG Target 3.3 Communicable Diseases, which aims to “By 2030, end the epidemics of AIDS, tuberculosis, malaria and neglected tropical diseases and combat hepatitis, water-borne diseases and other communicable diseases.”[2] Publications featured on Springer Nature’s World Hepatitis Day 2024 webpage span genetic research, the interplay between hepatitis and other illnesses, and new approaches to prevent, diagnose and treat hepatitis. Chosen papers also discuss the social experiences of people living with hepatitis. Much of this research focuses on vulnerable groups or people living in low-income countries, mainly in Asia and Africa.

Testing

Testing for viral hepatitis is usually via blood samples, although dried blood spots (e.g. collected via a finger prick) may be used when blood tests are difficult to take or analyse. The WHO “Guidelines on hepatitis B and C testing” 2017 mention areas in which further research should be undertaken, including testing strategies and validation of more tests to use simpler methods of sample collection, for example saliva.[3] This will help to address the issue of undiagnosed hepatitis in areas where it is difficult to collect blood samples. The WHO released further guidelines on hepatitis B on March 29th 2024 which identified priority areas for action, including improvements in point of care diagnostics and testing for hepatitis D.[4]

There remains a gap in testing and treatment. Currently, over 80% of people living with hepatitis do not have access to testing or medication, despite many key interventions being cost-effective.[5] In 2022, only 13% of those living with chronic hepatitis B had been diagnosed.[6] This is because the public health response to viral hepatitis has been underfunded, particularly affecting groups which have limited access to healthcare services such as people living in rural areas in low-income countries. To increase equitable access to hepatitis prevention and treatment, funding needs to increase in these areas. A WHO costing analysis stated that to achieve hepatitis elimination targets an additional US$6 billion in funding is required each year between 2016 and 2030 in low- and middle-income countries.[5] Policies can be used to encourage and direct funding to appropriate areas.

Effective interventions can be made when there is early diagnosis of hepatitis infections, and some positive strategies are already aiding the early identification of affected patients. The WHO Global Health Sector Strategies 2022-2030 outline actions to offer all pregnant women routine screening for chronic hepatitis B.[7] In the UK, many cancer patients are now being screened prior to starting chemotherapy due to the risk of reactivation of hepatitis B during treatment.[8] Since May 2023 the NHS offers free hepatitis C home testing kits which can be ordered online, and there has also been NHS investment in portable one-hour liver testing units in order to reach more people at risk of hepatitis-related liver disease.[9] Many UK hospitals offer routine screening for hepatitis B and C (and HIV) for adult patients who attend the Emergency Department and already require other blood tests. This approach has significantly reduced hepatitis-C-related deaths, with one statement reporting a reduction by 35%.[10]

Treatment

While over 95% of people who have hepatitis C can be cured using direct-acting antiviral medicines, there is currently no cure for chronic hepatitis B.[11] It can be managed by highly effective drug treatments which reduce progressions of liver disease and incidence of hepatocellular carcinoma and improve long term survival. However, treatment rates are currently low. The WHO Global Hepatitis Report 2024 outlines actions to improve access to health services and products worldwide. The guidelines simplify the eligibility criteria for medication, meaning more people will be able to receive treatment.[12] Major improvements in access to hepatitis B testing and treatment are required to achieve the goal of elimination of hepatitis.

[Map showing estimated numbers of chronic hepatitis B and hepatitis C infections per region in 2022. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Accessed: July 1, 2024. https://www.cdc.gov/hepatitis/global/index.html]

Vaccination

Vaccinations are important in reducing hepatitis infections among mothers and babies. Universal infant hepatitis B immunisation, including vaccination administered within 24h of birth followed by another 2 or 3 doses, is 90-95% effective in preventing infection and reducing new infections among children. Protection lasts at least 20 years and is probably lifelong. However, immunisation at present is only administered to 45% globally, with especially low coverage (18%) in African regions.[6] The 2024 WHO guidelines provide an additional option of using antiviral prophylaxis for all hepatitis B-antigen positive pregnant mothers, in addition to the infant vaccination.[4]

There is no effective hepatitis C vaccine, so prevention strategies are crucial to reducing exposure to the virus in higher risk populations. To protect against transmission, safe sex practices are encouraged including the use of barrier protective measures. Blood safety schemes such as needle exchange programmes can reduce hepatitis C transmission rates among people who inject drugs.[13]

The Infected Blood Inquiry: Increased public engagement with hepatitis issues?

Public awareness of hepatitis in the UK may be increased by the Infected Blood Inquiry. This independent public statutory inquiry has been examining cases between 1970 and 1998 where people were given blood infected with viruses, often via blood transfusions. The Inquiry’s report, published on 20 May 2024, states that institutions and government should react quickly to future blood infection threats.[14] Media articles on the Infected Blood Inquiry are reporting themes which are common with World Hepatitis Day, including that many people are unknowingly living with hepatitis. The report acknowledges the damaging effects that hepatitis can have on individuals and their families, and similarly World Hepatitis Day aims to increase the visibility of people living with hepatitis and encourages their voices to be heard.

Conclusion

World Hepatitis Day 2024 is an opportunity to encourage action and engagement from individuals, governments and organisations. Hepatitis-related research provides evidence that can be used to improve policy, advocate for increased funding, and encourage public uptake of hepatitis prevention and intervention schemes. Highlighting Springer Nature content on World Hepatitis Day celebrates the progress being made, while also bringing to light the challenges still to be overcome in order to eliminate viral hepatitis by 2030.

For more Springer Nature content on hepatitis, visit our World Hepatitis Day 2024 webpage.

Citations

[1] "Hepatitis." WHO. [Accessed: July 1, 2024]. https://www.who.int/data/gho/data/themes/chronic-viral-hepatitis

[2] "SDG Target 3.3 Communicable diseases." WHO. [Accessed: July 1, 2024]. https://www.who.int/data/gho/data/themes/topics/sdg-target-3_3-communicable-diseases

[3] WHO. "Guidelines on hepatitis B and C testing." February 16, 2017. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241549981

[4] WHO. "Guidelines for the prevention, diagnosis, care and treatment for people with chronic hepatitis B infection." March 29, 2024. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240090903

[5] "World Hepatitis Day 2019: Top 10 messages for policymakers." WHO. [Accessed: July 1, 2024]. https://www.who.int/campaigns/world-hepatitis-day/2019/10-messages-for-policymakers

[6] Easterbrook, Phillipa et al. "WHO 2024 hepatitis B guidelines: an opportunity to transform care." The Lancet Gastroenterology and Hepatology (April 10, 2024): p493. https://www.thelancet.com/journals/langas/article/PIIS2468-1253(24)00089-X/fulltext

[7] WHO. "Global health sector strategies on, respectively, HIV, viral hepatitis and sexually transmitted infections for the period 2022-2030." Geneva (2022): p29. https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/360348/9789240053779-eng.pdf?sequence=1

[8] UK Chemotherapy Board. "Position Statement on Hepatitis B Virus Screening and Reactivation Prophylaxis for Patients Planned to Receive Immunosuppressive SACT." February 8, 2022. https://www.uksactboard.org/_files/ugd/638ee8_241e17302c5342499e2d0feb62ea3351.pdf

[9] "Get a free home test for hepatitis C." NHS. [Accessed: July 1, 2024]. https://hepctest.nhs.uk/ & "NHS expands ‘one-hour’ liver testing to help detect and eliminate Hep C." NHS. https://www.england.nhs.uk/2024/04/nhs-expands-one-hour-liver-testing-to-help-detect-and-eliminate-hep-c/

[10] Gillyon-Powell, Mark. "Emergency department opt out testing for HIV, hepatitis B and hepatitis C: The first 100 days." NHS England. November 29, 2022. https://www.england.nhs.uk/long-read/emergency-department-opt-out-testing-for-hiv-hepatitis-b-and-hepatitis-c-the-first-100-days/

[11] "Hepatitis C." WHO. [Accessed: July 1, 2024]. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/hepatitis-c#

[12]WHO."Global hepatitis report 2024: action for access in low- and middle-income countries." Geneva (April 9, 2024). https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240091672.

[13] Kågström, E. et al. "Prevalence, risk factors, treatment uptake and treatment outcome of hepatitis C virus in people who inject drugs at the needle and syringe program in Uppsala, Sweden." Harm Reduction Journal, 77 (June 16, 2023). https://harmreductionjournal.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12954-023-00806

[14] Langstaff, Sir Brian. Infected Blood Inquiry: The Report. London (May 20, 2024). Vol.1, p28. https://www.infectedbloodinquiry.org.uk/reports/inquiry-report

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in