World Ovarian Cancer Day - Q&A with Dr Trevor Shepherd

Published in Cancer, Genetics & Genomics, and General & Internal Medicine

Trevor Shepherd is an Associate Professor at Western University and Scientist in the Mary and John Knight Translational Ovarian Cancer Research Unit in London, Ontario, Canada. His ongoing research program investigates the cellular reprogramming events that occur during the spread of ovarian cancer with a particular focus on three-dimensional cell culture models and patient-derived tumour samples. He is an Associate Editor for Journal of Ovarian Research.

Trevor Shepherd is an Associate Professor at Western University and Scientist in the Mary and John Knight Translational Ovarian Cancer Research Unit in London, Ontario, Canada. His ongoing research program investigates the cellular reprogramming events that occur during the spread of ovarian cancer with a particular focus on three-dimensional cell culture models and patient-derived tumour samples. He is an Associate Editor for Journal of Ovarian Research.

Why did you decide to go into your field of research?

I entered the field quite naively in the early 2000s after finishing my PhD studies on transgenic mouse models of breast cancer. I thought I could quickly and easily apply my skills to ovarian cancer. However, ovarian cancer is an entirely different disease, complex in its different histotypes. Little was known at the time about specific disease-causing mutations and fewer groups were studying this cancer especially when compared with breast cancer. As a new postdoctoral researcher, this fuelled my passion to take on the challenge and make use of the opportunity to pursue new ideas and develop new research models in an understudied human cancer. Twenty years later, I continue to study ovarian cancer since I have witnessed tremendous growth in our field, with a greater understanding of disease origins, a diversity in cell culture and mouse models that have been developed, and a much larger and highly collaborative network of researchers around the world. In addition, over the years I have had many opportunities to interact closely with people impacted by this disease - patients, family members and friends - who support our research in so many ways. This keeps me motivated and invested in continuing the research we still need so desperately.

How has research into ovarian cancer developed over the course of your career?

In my opinion, there are two research discoveries in ovarian cancer research early in this century that have revolutionized our thinking of this disease and stimulated an explosion of new research ideas and directions. The first would be the discovery by several different groups that the origin for likely all high-grade serous carcinomas of the ovary is in fact in the secretory epithelial cell of the distal fallopian tube. This reset the development of new, more accurate mouse models of high-grade serous ovarian cancer, and spawned a critical re-evaluation of the cell of origin for the other histotypes of this disease as well. The second would be the landmark paper published by The Cancer Genome Atlas Network in Nature on the genomics of hundreds of serous ovarian tumours. In fact, this represented the very first published report from the TCGA, which put ovarian cancer on an international cancer research radar. This study identified TP53 mutations as a nearly universal hallmark for high-grade serous cancer in addition to the tremendous copy number alterations across every tumour. Together this showed that TP53 mutation and high genomic instability are the key early drivers of this ovarian cancer histotype.

What research are you currently working on and what impact do you expect and hope it will have on the field?

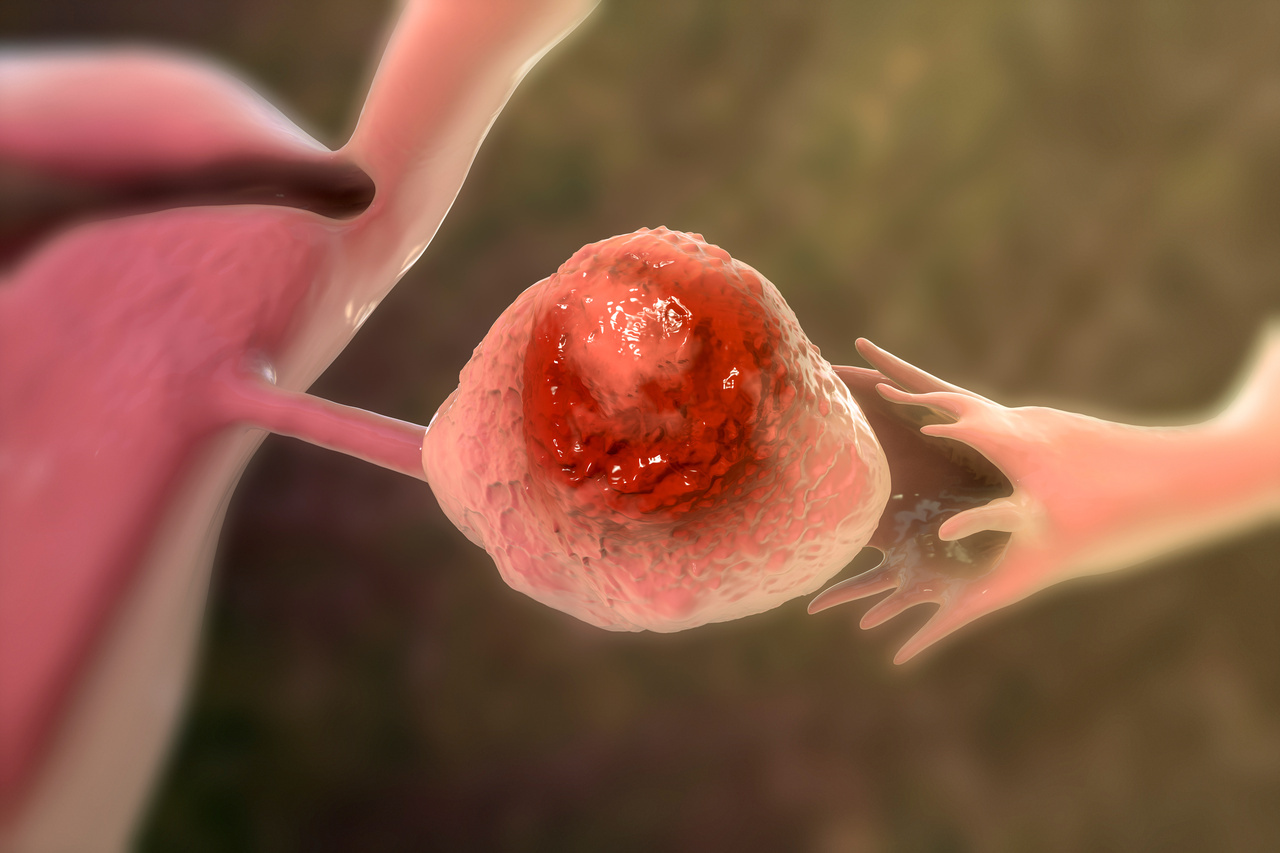

Most epithelial ovarian cancer patients are first diagnosed with advanced disease. Ovarian cancer metastasis occurs by direct dissemination of malignant cells into the peritoneal cavity, oftentimes within clusters we call spheroids. My research program has focused on studies using in vitro models of metastasis, by culturing cell lines and primary patient ascites-derived cells in suspension where ovarian cancer cells aggregate into 3D spheroids. We have interrogated the numerous molecular, cellular, and biochemical changes that occur in ovarian cancer spheroids and discovered that massive intracellular reprogramming takes place. Ovarian cancer spheroid cells activate bioenergetic stress pathways, undergo epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition, induce cytoprotective macroautophagy, and many cells enter a state of quiescence. This represents a potential "dormant" phenotype that protects ovarian cancer cells from cytotoxic chemotherapy, yet the cells undergo a dormant-to-proliferative switch once spheroids reattach to a new site. We are seeking to determine whether key signaling pathways and processes that are activated in spheroids represent new therapeutic vulnerabilities in the context of metastatic disease.

What are your hopes for progress in the future?

The standard therapy for epithelial ovarian cancers remains aggressive cytoreductive surgery and cytotoxic combination chemotherapy regardless of histotype. Yet we have a much better understanding that each histotype likely represents a different disease, given their distinct genetic mutations and cells-of-origin. Armed with this knowledge, research is heading in a direction where future patients may be treated with therapies more specific to their histotype. We have already seen improvements in patient outcomes with the application of PARP inhibitors for high-grade serous carcinoma with BRCA gene mutations or homologous DNA repair deficiency. This example fuels the hope for more tailored therapies in the future according to tumour histotype that could yield better treatment responses, not to mention a greater armament of agents to treat this aggressive and complex group of malignancies.

For more research on ovarian cancer, check out our article highlights campaign in Journal of Ovarian Research.

Follow the Topic

-

Journal of Ovarian Research

This is an open access, peer reviewed, online journal that aims to provide a forum for high-quality basic and clinical research on ovarian function, abnormalities, and cancer.

Your space to connect: The Cancer in understudied populations Hub

A new Communities’ space to connect, collaborate, and explore research on Cancers, Race and Ethnicity Studies and Mortality and Longevity!

Continue reading announcementRelated Collections

With Collections, you can get published faster and increase your visibility.

Stem Cells in Ovarian and Tubal Biology: Defining their Roles in Fertility and Disorders

The potential contributions of “stem cells” to ovarian and tubal biology are becoming more apparent with time. Whether they be embryonic or adult stem cells, be of a “normal” cell lineage or cells that have acquired stem-like properties (i.e., cancer stem cells), these unique cells can positively or negatively impact ovarian and tubal homeostasis. Stem cells of the ovary and tube include germ cells, cells that evolve to become thecal or granulosa of the follicle, stromal or epithelial cells of the ovary, and the oviduct.

The dynamic nature of these individual reproductive structures and their collective cellular subtypes suggests that the functional contributions of their unique stem cells will be equally diverse and complex. Their contributions in maintaining the cyclic changes associated with the development/maturation of the oocyte or follicle, response to injury (i.e., wound healing of the ovarian surface epithelium in response to ovulation or luteal development in response to an LH surge, etc.), or seeding the microenvironment of the oviduct allowing for the bidirectional activity of germ cells have yet to be fully explored. Additionally, stem cells or cells that take on stem-like properties likely play a role in the pathology of the ovary or tube, giving rise to benign and or malignant tumors.

A better understanding of the contributions of these specialized cells may prove helpful in maintaining fertility as well as the prevention and or treatment of aberrant/malignant conditions. The proposed focused issue seeks to compile reviews, original scientific reports, and commentaries, centralizing the most recent knowledge of ovarian and tubal stem cells for our audience.

We are committed to supporting participation in this issue wherever resources are a barrier. For more information about what support may be available, please visit OA funding and support, or email OAfundingpolicy@springernature.com or contact the Editor-in-Chief.

Publishing Model: Open Access

Deadline: Jun 23, 2026

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in