100 years since the Great Influenza Pandemic

Published in Microbiology

It seems timely to launch this Nature Microbiology community channel to commemorate the centenary of the 1918 influenza pandemic in the midst of a particularly bad 2017-2018 flu season, in which almost everyone knows somebody (or has suffered directly) the consequences of coming down with a bad case of the flu. Recent news coverage, such as here, here, here and here, makes it easier to imagine how things were during 1918. Except that, as John M. Barry - of "The Great Influenza" fame- explains in his thought-provoking Comment, the media and officials then were intent on playing down the dangers to avoid panic, which ended up frightening the population even more, as people saw a clear disconnect between the reality they were living and the messages they were receiving. We may now have gone too far the other way, if the Daily Mail is anything to go by (which this editor thinks is not the case).

So what happened in 1918-1919? There are many excellent accounts, such as the book above, and a lot of information around the web, so I will not belabor the point here. The numbers are staggering; it is estimated that one-fifth of the world’s population (about two billion at the time) came down with the disease, and it killed at least 35 million people and up to 100 million by some accounts - which would be equivalent to 140 million to 425 million people today. To put things in perspective, the death toll was higher than all the combat fatalities from all wars of the 20th century combined.

Briefly, it was a pandemic staged in three waves. In late 1917, U.S. military pathologists described a new disease with high mortality (which later was recognized to be the flu), and the first official report was in Haskell County, Kansas, in January 1918, although where the strain had originally come remains subject of debate. The first confirmed outbreak was relatively benign (considering the death toll) and occured in the spring at Camp Funston, Fort Riley, Kansas, a military training camp preparing American troops for deployment in World War I. On 4 March, the company cook Albert Gitchell reported sick and by noon on 11 March over 100 soldiers were in the hospital. Within days, 522 men at the camp had reported sick. This first wave was followed by the emergence of a mutated, extremely virulent virus that, aided by troop movements in World War I, quickly spread worldwide and caused millions of deaths during the following fall (especially the months of October and November). A milder third wave occurred at the beginning of 1919, although by then a lot of the surviving population was likely immune.

One aspect that made it particularly frightening was the speed with which people worsened and died. By some accounts, people could wake up feeling well, feel sick in the early afternoon, and die at night. Those who survived initially, often suffered a secondary bacterial pneumonia that was ultimately the cause of numerous deaths.

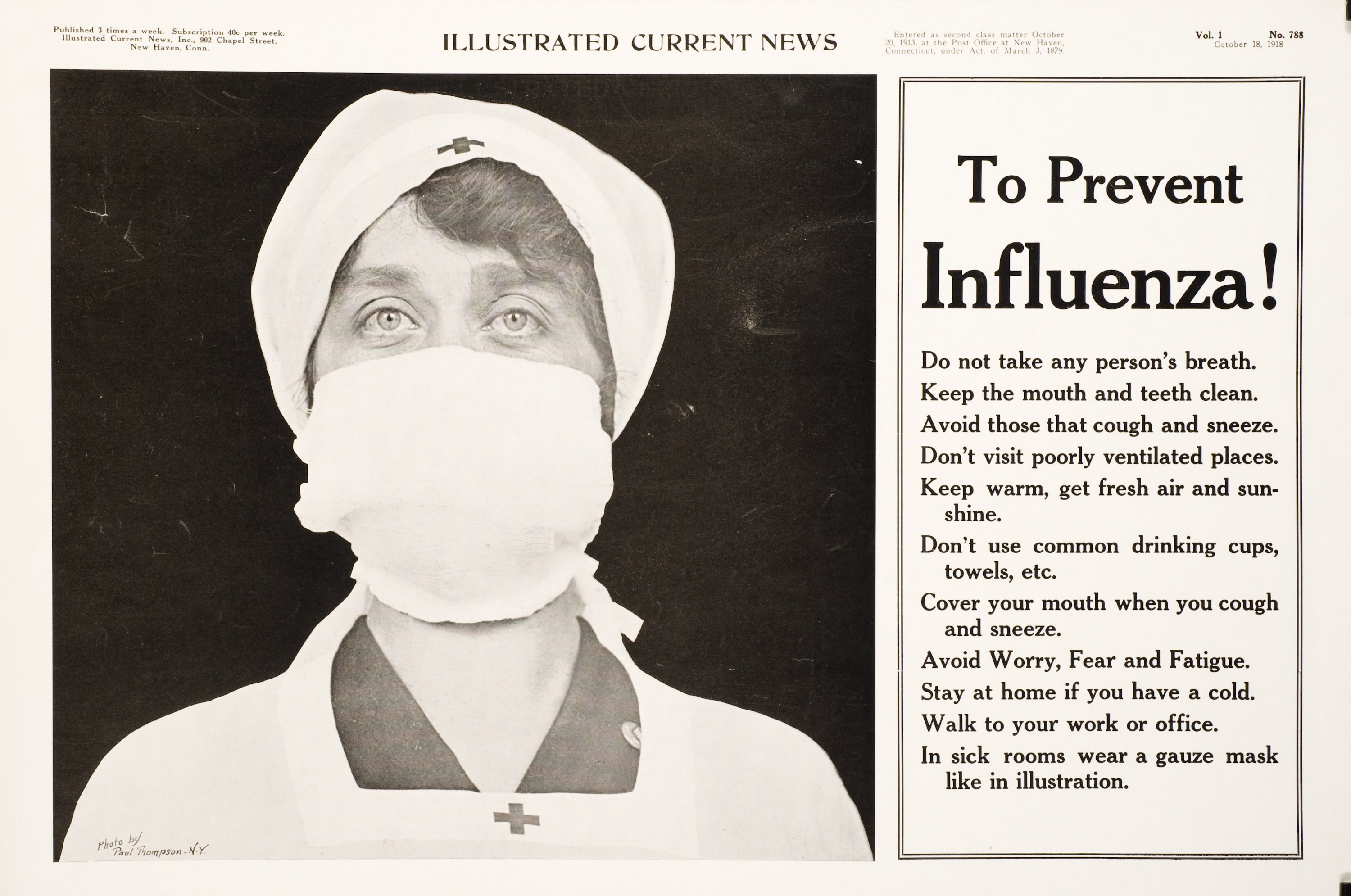

To prevent influenza - US Library of Congress (public domain)

We have taken the opportunity afforded by this anniversary to ask people working on different aspects related to influenza management and research to share with us their thoughts on the 1918 pandemic, the current state of the field and of their research, lessons learned and lessons yet to learn. John Barry speaks of the socioeconomic impact that the pandemic had in its time and what can be learned from how it was handled. Peter Palese, who together with his colleagues at the Mount Sinai School of Medicine, has elucidated some of the basis for the virulence of the 1918 strain, discusses the needs for a better vaccine and the prospects to develop one that provides universal coverage. And in a series of interviews, Keiji Fukuda, Nikki Shindo, Elodie Ghedin, Adolfo Garcia-Sastre, Kanta Subbarao and Yoshi Kawaoka discuss the public health implications of the 1918 pandemic and subsequent ones, the development of the reverse genetics system that has made influenza virus genetically tractable, influenza variability and evolution, and pathogenesis in its multiple hosts.

One of the greatest challenges in the field is to develop better vaccines: platforms that enable production with sufficient speed to meet demand in a timely manner and immunogens that confer broad -if not universal- protection. As this years' season again atests, a bad flu year is often caused by breakout strains to which current vaccines no longer confer good protection (vaccine efficacy in Australia to this season's most prevalent A/H3N2 strain has been reported to be 5-19%).

One last point I'd like to make (being Spanish and all) is that the 1918 pandemic was not the "Spanish flu" by any reasonable measure. In 1918, the Spanish press reported on the flu more than others, likely because Spain did not participate in WWI, but the virus was not initially identified in Spain, nor did it cause comparatively more deaths there. As Ian Mackay and Katherine Arden discuss, in relation to this season's supposedly Aussie flu, "We can't be sure of where flu originates, and that doesn't really matter anyway". Given the stigma, and often the economic consequences, that come with such names, we would do better avoiding them.

We hope this channel gives you food for thought!

Follow the Topic

-

Nature Microbiology

An online-only monthly journal interested in all aspects of microorganisms, be it their evolution, physiology and cell biology; their interactions with each other, with a host or with an environment; or their societal significance.

Related Collections

With Collections, you can get published faster and increase your visibility.

The Clinical Microbiome

Publishing Model: Hybrid

Deadline: Mar 11, 2026

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in