A 1,805-day exploration revealing how network structure shapes artificial neural networks

Published in Computational Sciences, Mathematics, and Statistics

Preface

This post was written by Haoling Zhang (from the AI4BioMedicine Laboratory at King Abdullah University of Science and Technology) based on his research notes and has been reviewed and supplemented by the co-authors. It serves as supplementary reading to our published work, offering a behind-the-scenes account of its long journey — or perhaps just the authors' meandering recollections of it. Naturally, it inevitably carries the subjectivity inherent to personal narration. If you would like to glimpse this 1,805-day journey, we would be grateful if you could spend ten minutes with us.

What motivated this journey?

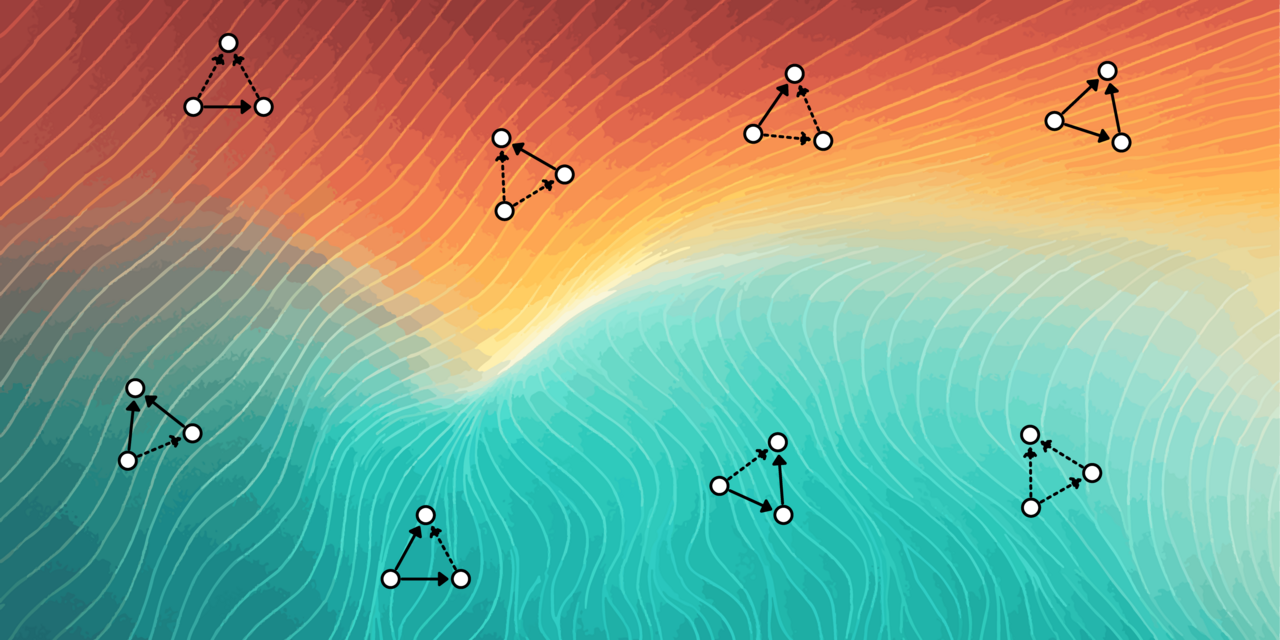

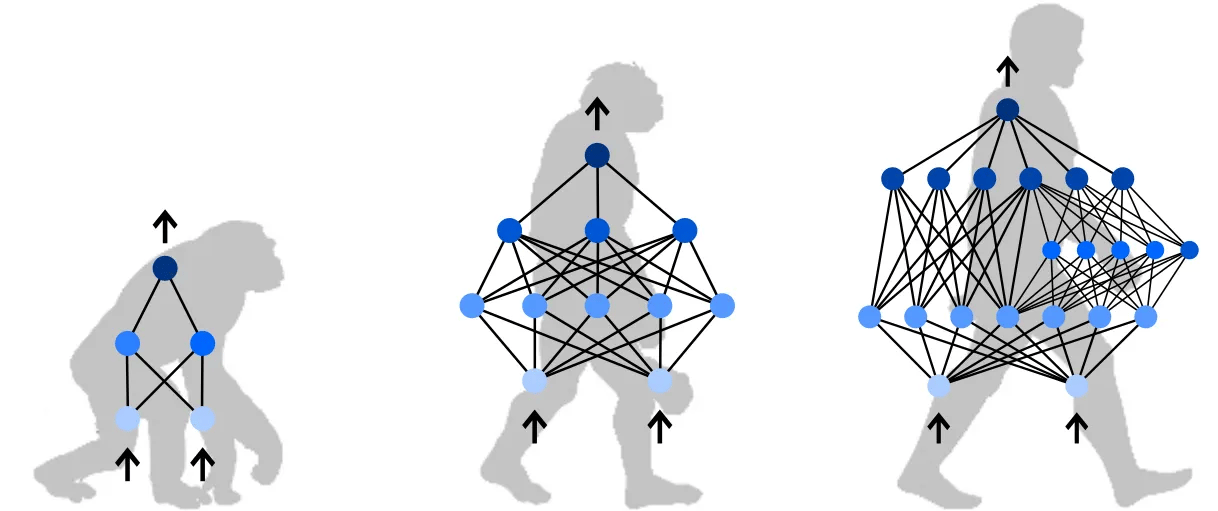

In early 2020, while finalizing a conference paper [1] on neuroevolution (i.e., a family of strategies that evolve both the structural topology and the parameter value of artificial neural networks), we noticed something intriguing. Artificial neural networks generated by geometry-based evolutionary strategies seemed to learn tasks faster and tolerate noise better than those produced by the baseline [2]. At first, we thought that minor performance gaps in simple, toy control tasks would disappear once the neuroevolution methods were tested on more complex problems. But after our conference paper was published and we began exploring more sophisticated tasks, we observed that these differences persisted. On the contrary, they became even more pronounced. This unexpected consistency caught our attention.

Initially, we assumed that the advantage came from the evolutionary strategies themselves. Yet when we looked closely at the individual artificial neural networks they produced, we noticed that their performance still varied from one instance to another. The variations appeared to follow the network structures rather than the algorithmic details. This pattern suggested that the geometry-based strategy implicitly favored specific structural configurations, thereby influencing both how well the networks learned and their robustness.

This realization led us to focus on network motifs [3]: recurrent and statistically significant sub-networks that often act as the fundamental building blocks of larger complex networks. Network motifs have been widely studied in biology and social science, but surprisingly little in the context of artificial neural networks. When we looked for prior work, we found almost no systematic studies on how network structure shapes learning and stability in modern AI systems. While it was tempting to borrow analogies from other fields, we worried that doing so might be misleading: information propagation and performance measures in artificial networks behave very differently from those in natural ones.

How did the exploration unfold?

When we set out to explore how network motifs might influence the performance of artificial neural networks, we quickly realized how little the machine learning field had to offer. There were almost no methods designed to study such motifs in this context. To make progress, we had to build our own analytical methods from scratch, testing one idea after another to see what could actually work. It was, in many ways, a classic stepwise and highly bottlenecked exploration process.

The study formally began with a project discussion on October 20, 2020. From there, the work grew into a long-term collaboration. By August 2023, after nearly three years of continuous effort, we had designed and refined a set of analytical methods reliable enough — so we thought at the time — to support the main body of the study (i.e., static motif analytical method, dynamic motif analytical method, evolved network analytical method). Over this period, three analytical methods formed the backbone of our work, while more than ten others were merged, adjusted, or ultimately set aside during development.

After spending more than half a year re-running every experiment from scratch and assembling extensive collection of fully reproducible results, we felt that the study had finally reached a stable and internally coherent form. When we thought that a set of original analytical methods combined with solid insights would finally bring a happy ending to the three-year journey, reality had little patience for such idealism.

Beginning on July 10, 2024, the date of our first substantive interaction with academic publishers, the direction of the story began to shift. What had started as a project driven purely by curiosity gradually became an exploration of how our work might speak to a broader community, not just to ourselves. Not long after, we encountered a series of desk rejections, each one a reminder that, although our work felt internally complete, we had not yet clarified how it would directly engage the community's interest.

This became clearer during our interactions with the Nature Computational Science editorial team, since they offered support that went well beyond a routine decision letter. Their suggestions pushed us to articulate more explicitly how our study connects to real-world challenges. In hindsight, this step fundamentally improved the work: it forced us to frame what began as a purely structural investigation in a way that speaks to actual use cases, rather than leaving it as an isolated theoretical analysis. Although our revision did not ultimately align with the journal's editorial priorities, the depth of their engagement sharpened the study's applied relevance in ways we could not have achieved on our own and showed us, in a very concrete way, what the phrase "publish with us" can mean. It goes without saying, that we were and are immensely grateful for this constructive feedback.

When the manuscript reached the Nature Communications editorial team, the countdown to sharing our work with the community officially began. The reviewer reports were encouraging: both reviewers responded positively to the value of the study and offered a series of insightful and constructive suggestions. Crucially, their feedback highlighted a gap that we had not fully addressed — the need to bridge the motif-level analyses (static and dynamic) with the network-level behaviors observed in evolved architectures. This prompted us to develop the fixed network analysis, which completed the last missing link in the study's conceptual structure.

After incorporating these refinements, the manuscript was accepted in principle by Nature Communications on September 29, 2025: exactly 1,805 days after our first project meeting.

What insights were eventually gained?

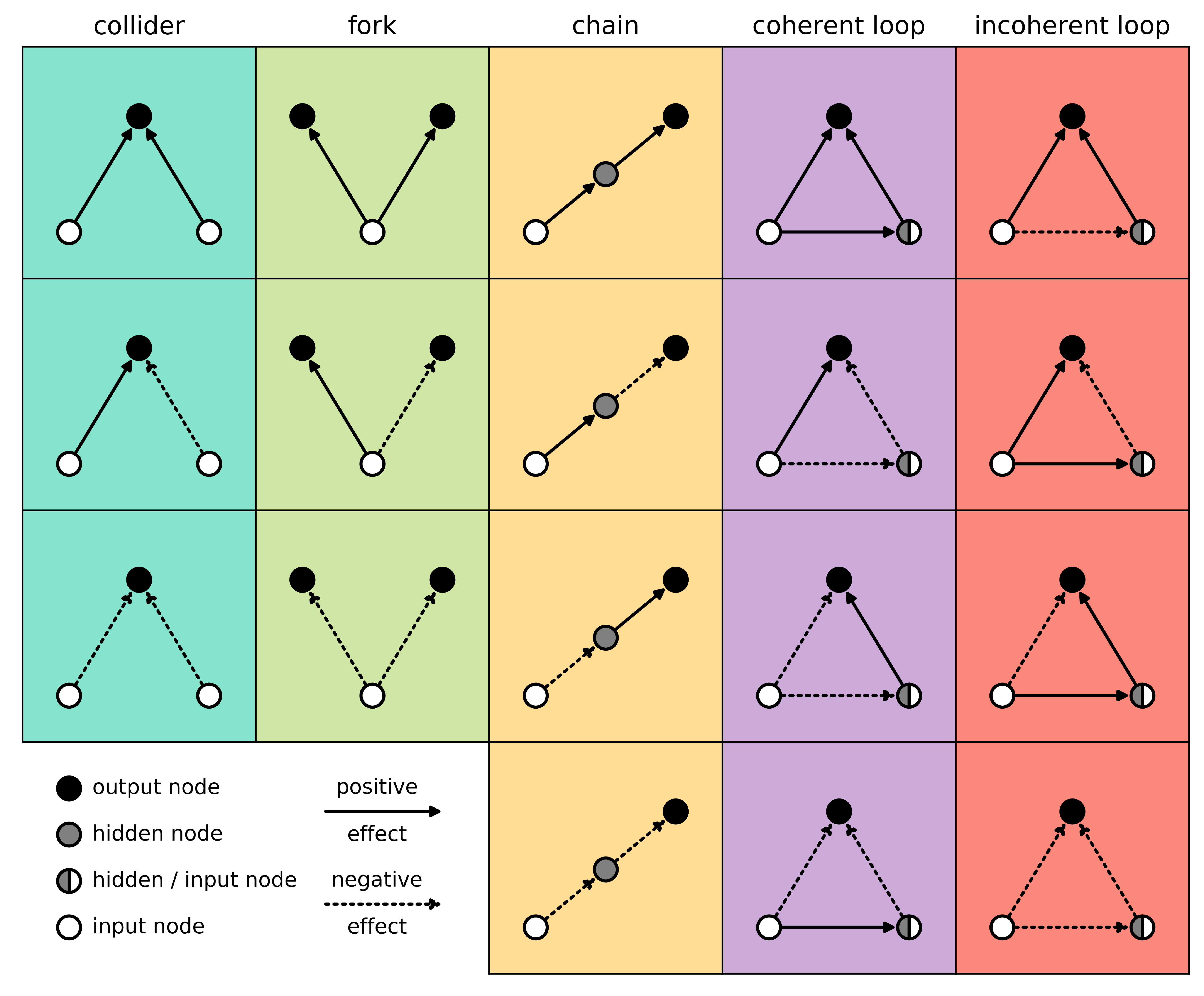

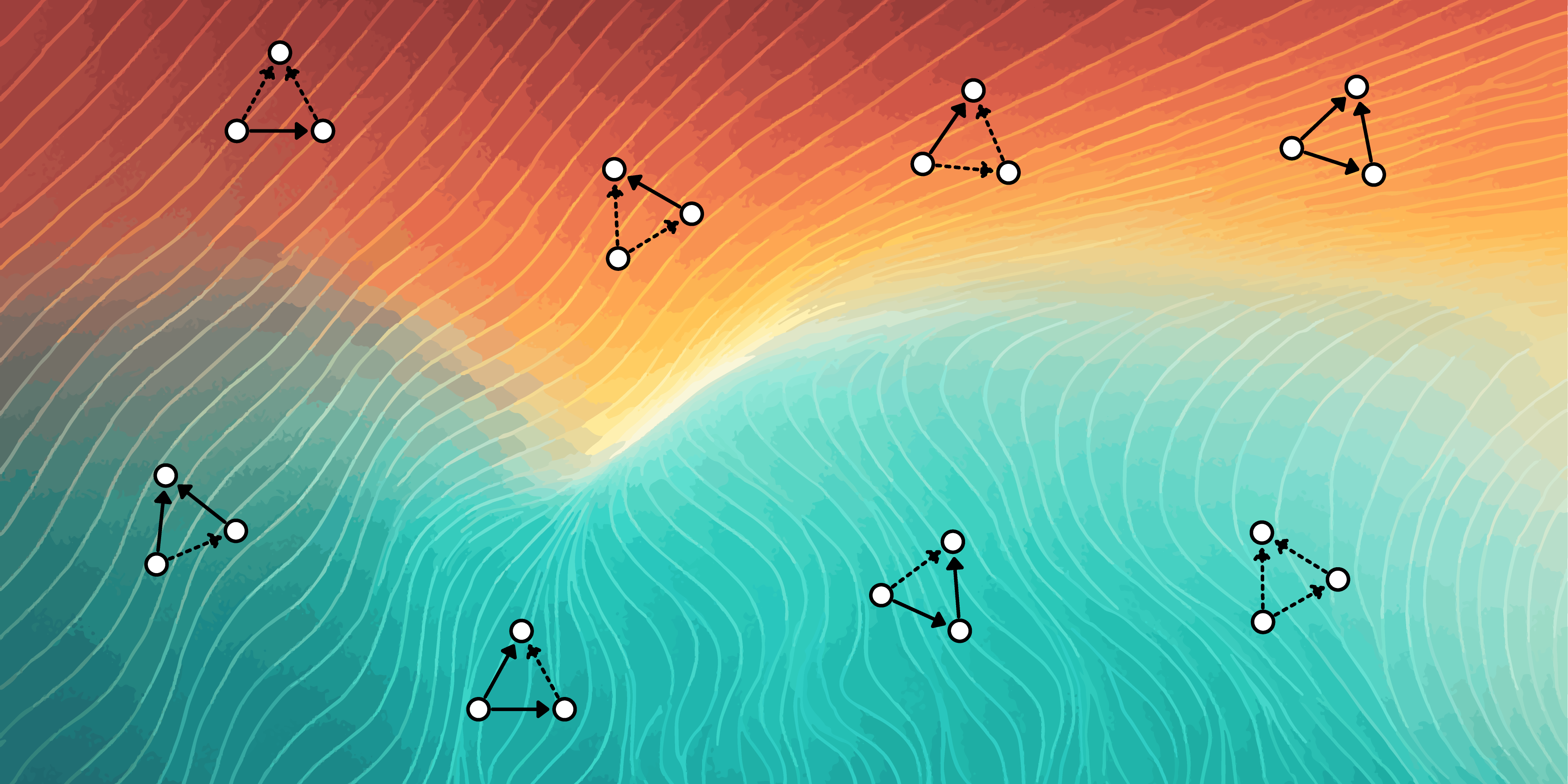

Among all three-node network motifs without self-loops, this study focused on three patterns with an explicit role in information aggregation: the collider, the coherent loop, and the incoherent loop. In our study, the two distinct loop types served as the "experimental" structures, while the collider motif (essentially a loop missing one edge between two input nodes) served as a natural control. This simple contrast between coherent and incoherent loops turned out to be surprisingly informative for understanding how motif structure shapes learning behavior and noise resistance.

Across all analyses, one pattern emerged: incoherent loops allow neural networks to learn in a richer, more stable way than coherent loops. Under classical gradient-based training, networks dominated by coherent loops tended to "rush" toward the steepest parts of the learning landscape first, leaving the rest to be filled in later. In contrast, incoherent-dominant networks showed no such early rush. Because they explored the landscape more evenly, they handled noisy training conditions much better.

In real-world scenarios, noise is almost impossible to eliminate. During the early training phase, such noise can easily mislead a neural network because it cannot distinguish meaningful from non-meaningful signals. In these situations, networks with more incoherent loops stayed noticeably more stable and less confused. Importantly, this advantage did not end after training: when the trained models were later exposed to environmental noise, incoherent-dominant networks remained far more robust than coherent ones.

What can these insights bring to the community?

Our findings offer a new way to think about the design of artificial neural networks. Rather than relying solely on larger models or more data, our results show that even tiny structural patterns can meaningfully shape how a network learns, explores, and withstands noise. This perspective provides an interpretable structural lens that complements the dominant scaling view.

Which thoughts in this journey were worth sharing?

1. Never put all of our eggs in one basket.

We realized early on that a research project rarely unfolds in a linear or predictable way. Although the final publication appears cohesive, our starting point was the evolved network analysis that later became Figures 5 and 6. These early experiments showed that motif structure mattered, but when we tried to understand why and how to control motifs precisely, we quickly hit a wall. Evolved networks offered almost no leverage for fine-grained motif manipulation, and the project entered a period of stagnation.

This stagnation lasted nearly six months. During this time, we shifted attention to other ongoing work. While I was exploring a protein structure problem and working extensively with a protein structure database [4], an unexpected idea surfaced: if evolved networks made motif control difficult, why not build a controlled motif database ourselves? That thought, coupled with a set of custom-designed metrics [5], eventually became the static motif analysis in Figure 2, providing a clean way to examine motif behavior under well-defined conditions.

But this approach soon reached its own limits. The static analysis relied on coarse parameter sampling and revealed global differences between coherent and incoherent loops, but could not capture the continuous, fine-grained updates that occur during gradient descent. The project entered another period of stagnation.

Roughly three months later, a discussion on adversarial neural networks [6] revealed the missing link we had been searching for. Adversarial updates offered exactly the kind of controlled yet dynamic perturbation we needed. This insight became the dynamic motif analytical method and allowed us to study motifs at the micro-scale of continuous adaptation. Once this method was in place, it provided the final piece we needed to complete the manuscript's initial form.

Looking back, the realization feels simple but profoundly true: if attention is focused on only one project, every obstacle becomes a dead end. When several lines of work are allowed to progress in parallel, ideas can cross-pollinate in unexpected ways. A stalled project can be revived by insights gained elsewhere, often at the very moment when one stops trying to force a solution.

2. Treat our reviewers as collaborators

The peer-review process for our manuscript was unusually smooth, and this experience is worth recording as a meaningful reflection. Notably, "smooth" here does not mean that the manuscript was accepted without substantial revision. Rather, it refers to something far more valuable: the discussions remained entirely centered on the science itself, free from conflicts of interest or obscured motivations. The reviewers engaged with the work as true collaborators, raising insightful questions and pushing us toward a clearer and more rigorous presentation of the ideas. We are grateful to the Nature Communications editorial team for assembling such a thoughtful and well-matched group of reviewers.

Both reviewers offered reports that were similar in tone and structure. They acknowledged the novelty of our work and the substantial effort behind it, while also offering clear, constructive suggestions for improvement. What stood out was their balanced perspective.

One reviewer explicitly recognized that completing all of the additional analyses they proposed would be beyond the scope of the current submission. Meanwhile, they noted that addressing none of the suggestions might also be suboptimal and encouraged us to consider whether a subset of quick, targeted tests could be feasible to add. This framing made it clear that their intention was not to impose an excessive workload, but to help us identify which refinements could meaningfully strengthen the manuscript.

The other reviewer pointed out readability issues and emphasized that some of their confusion about the results stemmed from the limited clarity of certain passages. They explicitly welcomed any clarification from our side, indicating that their intention was not to fault the logic or the work itself. They offered a remarkably detailed reader's perspective that illuminated where misunderstandings were likely to arise, which allowed us to pinpoint the specific content that needed clarification or revision quickly.

We took the reviewers' reports extremely seriously and regarded their feedback as an essential part of engaging responsibly with the community. Although we could not fully estimate the overall development effort and experimental workload, we nevertheless designed a corresponding plan for each suggestion they raised. Because we aimed to address all of these points and spent considerable time discussing the rationale and feasibility of each experiment, we requested an extension for the resubmission. The manuscript was also thoroughly reorganized following the recommended structure of motivation, design, observations, and summary for each subsection. The effort proved worthwhile. The results aligned with our expectations, and the updates were met with unanimous appreciation from the reviewers.

Although such a collaborative spirit between authors and reviewers might be uncommon, it is certainly something worth learning from. As authors, once we recognize that reviewers are ultimately our readers, it becomes our responsibility to present the work in a genuinely understandable way. At the same time, for reviewers, offering suggestions to improve a manuscript should go hand in hand with acknowledging the effort that went into it. After all, none of us truly knows how much work, frustration, or persistence lies beneath a manuscript that may still appear rough at first glance. At the very least, when we are fortunate enough to encounter such sincere work, we would strive to treat it with the same respect.

Closing remarks

It has taken us 1,805 days to carry this idea from a fleeting spark of curiosity to a completed study. Along the way, our questions evolved and the obstacles shifted — often in ways we did not anticipate at the outset. Our curiosity, too, was never constant. It wavered like a distant star, sometimes faint, sometimes bright, yet always returning just enough light to keep us moving forward.

By sharing this story, we hope it may be of some help to you. If any moment of this journey resonates with where you are now, or brings even a brief sense of steadiness amid whatever uncertainties you may be facing, then these 1,805 days will have meant more than we could have hoped.

References:

- Zhang, H. et al. Evolving neural networks through a reverse encoding tree. In 2020 IEEE Congress on Evolutionary Computation, 1–10 (IEEE, 2020).

- Stanley, K. O. & Miikkulainen, R. Evolving neural networks through augmenting topologies. Evolutionary Computation 10, 99–127 (2002).

- Milo, R. et al. Network motifs: simple building blocks of complex networks. Science 298, 824–827 (2002).

- Berman, H. M. et al. The protein data bank. Nucleic Acids Research 28, 235–242 (2000).

- Weng, T-W. et al. Evaluating the robustness of neural networks: an extreme value theory approach. In 2018 International Conference on Learning Representations, 1–18 (openreview.net, 2018).

- Goodfellow, I. J. et al. Generative adversarial nets. In 2014 Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 1–9 (NIPS, 2014).

Follow the Topic

-

Nature Communications

An open access, multidisciplinary journal dedicated to publishing high-quality research in all areas of the biological, health, physical, chemical and Earth sciences.

Related Collections

With Collections, you can get published faster and increase your visibility.

Women's Health

Publishing Model: Hybrid

Deadline: Ongoing

Advances in neurodegenerative diseases

Publishing Model: Hybrid

Deadline: Mar 24, 2026

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in