A glimpse into the role of auxiliary metabolic genes in cyanophages during infection

Published in Chemistry and Microbiology

Cyanobacteria are the most abundant photosynthetic organisms in the oceans. One of their survival mechanisms under nutrient limitation is the controlled degradation of their phycobilisome, large light-harvesting antenna complexes. A key protein in this process is NblA, which triggers phycobilisome breakdown and provides an immediate pool of amino acids.

Cyanophages often carry auxiliary metabolic genes acquired from their hosts that are thought to redirect host metabolism for the phage’s benefit. Over the years, reports emerged that freshwater cyanophages – viruses infecting freshwater cyanobacteria – carry their own version of the nblA gene, one such auxiliary metabolic gene. This raised an interesting question: Do cyanophages use NblA in the same way as their hosts, to degrade phycobilisomes, but for their own benefit? In other words, while cyanobacteria use NblA for survival, has the phage “weaponized” the gene to enhance phage progeny production or accelerate host lysis? Due to the lack of genetic tools for cyanophages at the time, this question could not be tested directly.

This changed when we discovered that marine cyanophages also carry nblA genes, and that its presence in these phages is far more widespread than was previously known. Around the same time, we developed a long-awaited method for engineering marine cyanophage genomes. This made the question: ‘what does viral NblA actually do during infection?’, experimentally accessible.

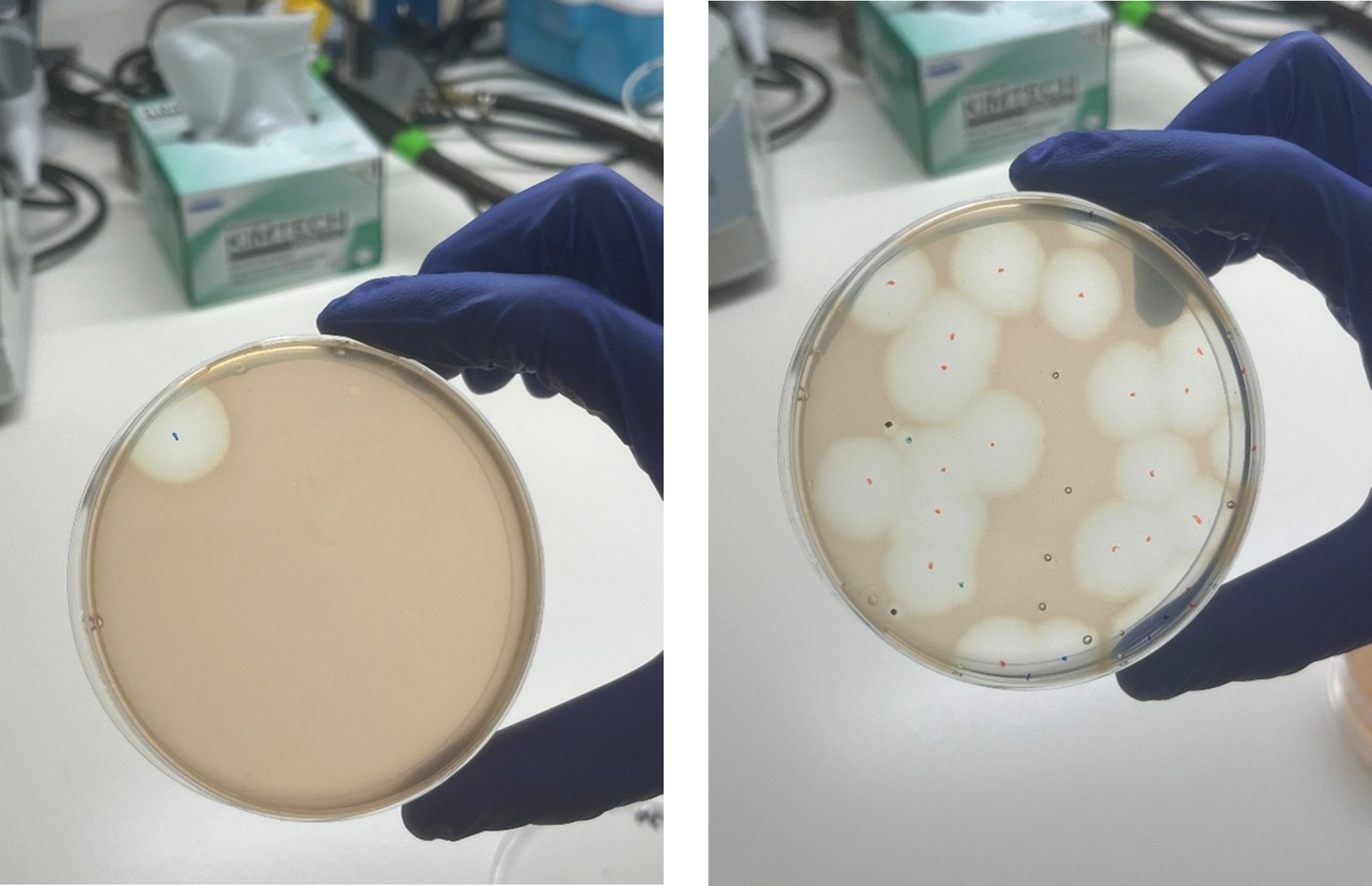

We generated a cyanophage nblA-deletion mutant. After several months of work: conjugating a deleted version of viral nblA into the host, infecting, screening for mutants, and isolating the phage, we finally obtained nblA-knockout cyanophages.

Conjugant colony (marked with a black circle) carrying a plasmid with deleted viral nblA, before (left) and after (right) transfer to liquid medium. Credit: Dr. Shirley Larom

We were eager, perhaps too eager, to perform the first infection experiment. However, during the plaque assay, the flask containing the nblA knockout mutant phage slipped and fell to the floor. Our much-anticipated first infection experiment had to be postponed. But once we recovered and repeated the experiment, the results were worth waiting for.

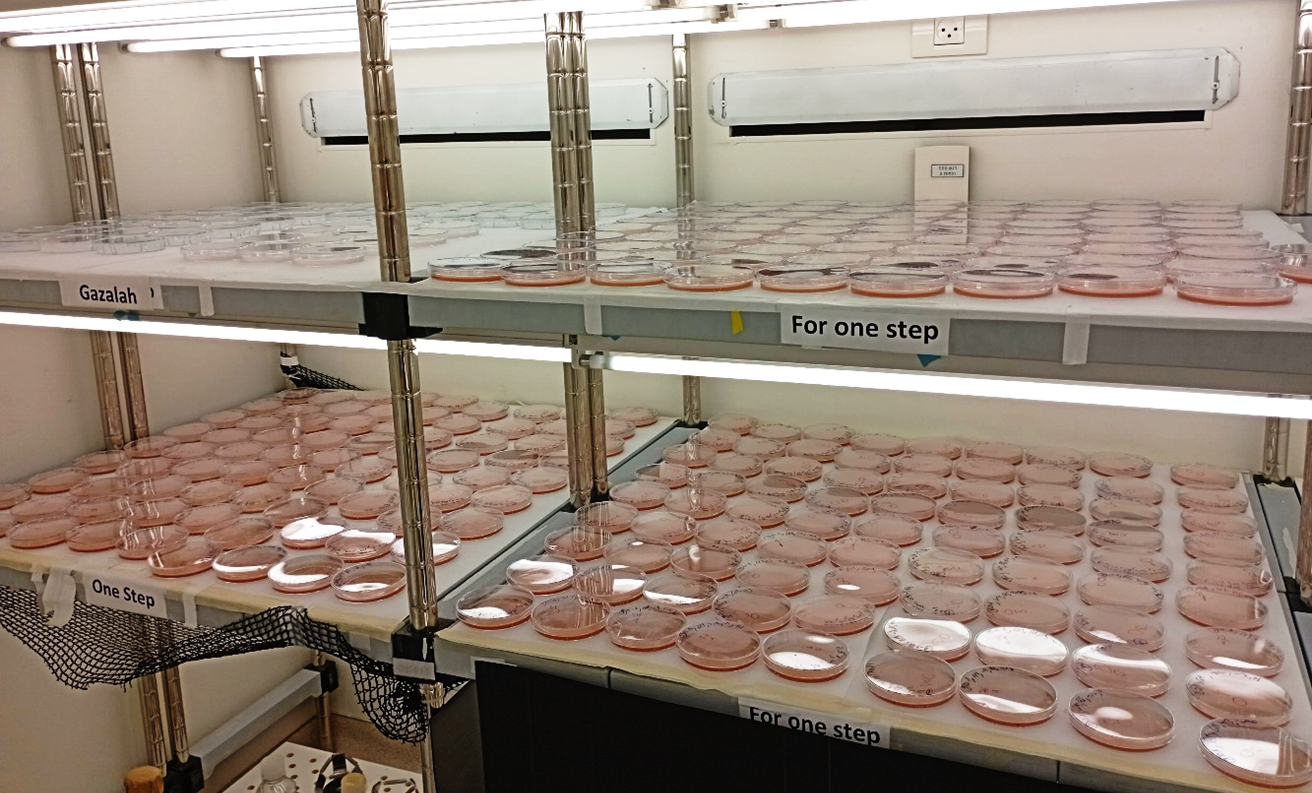

Plaque assay preparations - cyanobacterial plates. Credit: Dr. Shirley Larom

Plaques formed by cyanobacterial lysis after cyanophage infection. Credit: Dr. Shirley Larom

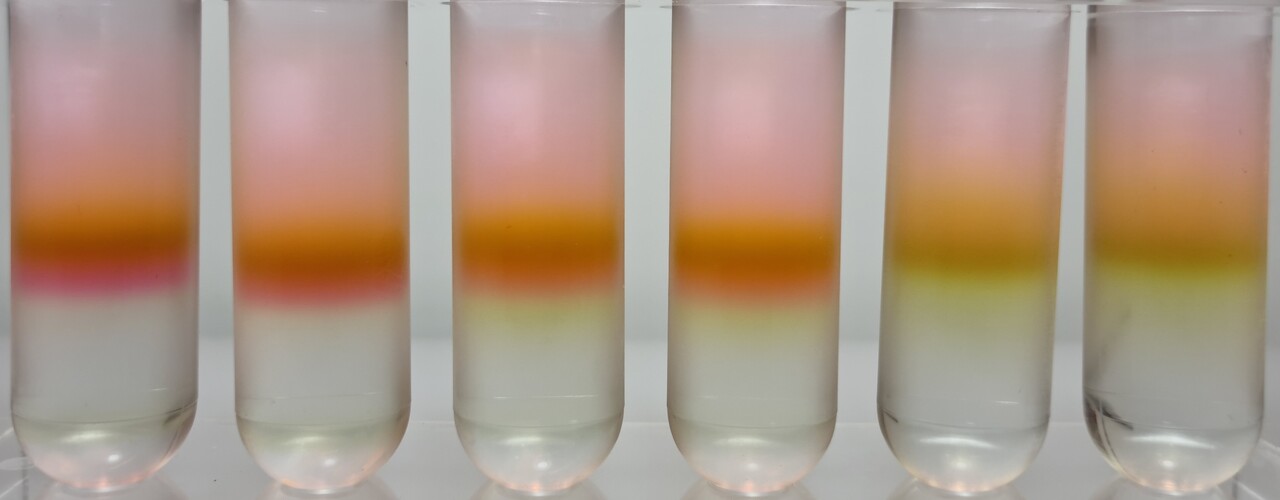

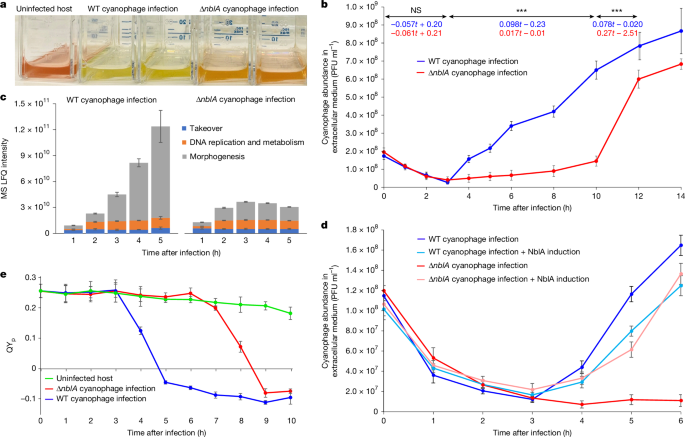

Once experiments resumed, we detected significant differences between the WT and mutant phage infections, in many of the parameters measured. This included a 3-fold faster infection cycle and a 50% reduction in host photosynthesis. Furthermore, we observed visible colour differences between the two phage infections, even during phage stock preparation, highlighting how significant the physiological effect of NblA on the host was.

Cyanophage lysate preparations. Cyanobacteria infected by WT (right) and mutant (left) cyanophages. Credit: Dr. Shirley Larom

To understand how viral NblA drives this transformation, we optimized an N-termini–enrichment proteomics method compatible with our organisms and complexes, and uncovered how viral NblA proteins induce proteolysis of the cyanobacterial phycobilisomes as well as other cellular proteins, with such high resolution that we could determine the exact amino-acid positions where cleavages occur. This allowed us, for the first time, to see the molecular signature of the viral NblA unfolding inside the cyanobacterial cell.

Together, the results draw a picture of a complex infection strategy. Cyanophages appear to maintain the host’s photosynthetic energy production by expressing other photosynthesis genes, while simultaneously using their nblA gene to rapidly degrade the massive host photosynthetic antennas. This dual action appears to rapidly generate a large supply of amino acids for virion synthesis.

By merging newly developed tools: marine phage genetic engineering, N-terminal proteomics, and advanced metagenomics, we were able to trace how one viral gene influences cyanobacterial light harvesting and likely affects photosynthesis in ocean ecosystems.

Follow the Topic

-

Nature

A weekly international journal publishing the finest peer-reviewed research in all fields of science and technology on the basis of its originality, importance, interdisciplinary interest, timeliness, accessibility, elegance and surprising conclusions.

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in