A heat tolerant wild coffee species that tastes like Arabica coffee

Published in Sustainability

The coffee we drink

Arabica coffee (Coffea arabica) is the world’s favourite coffee, comprising around 60% of all the coffee consumed worldwide. It is what most of us drink at home and in our favourite bars and cafes. The other main coffee crop species, robusta (C. canephora), is mainly used for instant coffee and in blends, as it is flavour is inferior to Arabica. For many coffee farmers robusta can be a challenge because it does not command the higher prices (usually at least double) paid for Arabica.

Arabica coffee, originating from the highlands of Ethiopia and South Sudan, is a cool-tropical plant with a mean annual temperature requirement of ~ 19⁰C. It is vulnerable to increasing global temperatures and coffee leaf rust, a fungal disease that has severely impacted coffee farms in Central and South America. Robusta occurs naturally in the low elevation forests of wet-tropical Africa and has some distinct advantages over Arabica. It grows and crops at a mean annual temperature of ~ 23⁰C, is resistant to certain strains of coffee leaf rust, and is also highly productive.

Coffee and climate change

Coffee farmers are already experiencing the negative influences of climate change. The long-term future for Arabica under climate change, and even robusta, looks challenging if not bleak. What are the options for sustainability and resilience for the coffee sector? So far, there has been limited progress in future-proofing the supply chain under climate change. Solutions for resilience include relocating coffee farming areas and adapting the farming environment, but these come with negative consequences for communities or impose cost challenges, respectively. A third, and much more workable solution would be the development of new, climate resilient coffee crops. However, finding a coffee that can tolerate high temperatures and other climate factors, whilst also satisfying consumer preferences for flavour, represents a major challenge.

A forgotten coffee species

Stenophylla coffee (Coffea stenophylla) is a forgotten coffee crop species from Upper West Africa, which has only recently been rediscovered in the wild. Various obscure publications from the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries reported an excellent taste for stenophylla coffee. There are, however, problems with accepting these historic reports. Sensory praise has been awarded to several other wild coffee species, but they have all been found to be greatly lacking in flavour quality. In addition, our views on flavour, and the methods we use to assess it, have changed considerably, even within the last few decades. The last sensory appraisal for stenophylla coffee was undertaken 100 years ago.

Sensory analysis

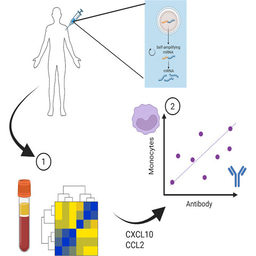

In 2020 we were able to acquire two samples of stenophylla coffee: one from the rediscovered population in Sierra Leone, and the other from plants grown at the Coffea Biological Resources Center on Reunion Island (Indian Ocean), originally collected many years ago from Ivory Coast. The Sierra Leone sample underwent an initial tasting by Union Hand-Roasted Coffee, in London, and then a full evaluation was made of the Ivory Coast sample by CIRAD, at their sensorial analysis laboratory in Montpellier, France. Subsamples were also sent out to other coffee experts. In total, a panel of 18 judges evaluated the flavour (taste and aroma) of stenophylla coffee, alongside Arabica and robusta. Most of the samples were tasted blind tasting, that is, the identity and origin of the samples, and the controls, were unknow to the judges

The results from the sensory evaluation were remarkable. Stenophylla coffee was found to have an excellent flavour, and, to our great surprise, tasted like Arabica coffee. The evaluation also revealed a complex flavour profile, natural sweetness, medium-high acidity, fruitiness, and good body (i.e., its texture; the way it feels in the mouth), as one should expect from high-quality Arabica. Desirable flavour notes included peach, blackcurrant, mandarin, honey, light black tea, jasmine, spice, floral, chocolate, caramel, nuts, and elderflower syrup. When asked if the stenophylla subsamples represented Arabica, most of the judges (81%) said yes (compared to 98% and 44% for the two Arabica control samples, and 7% for the robusta sample). Despite the high ‘Arabica-like’ score for stenophylla, 47% of the judges identified the sample as something new, suggesting a market niche for the rediscovered coffee.

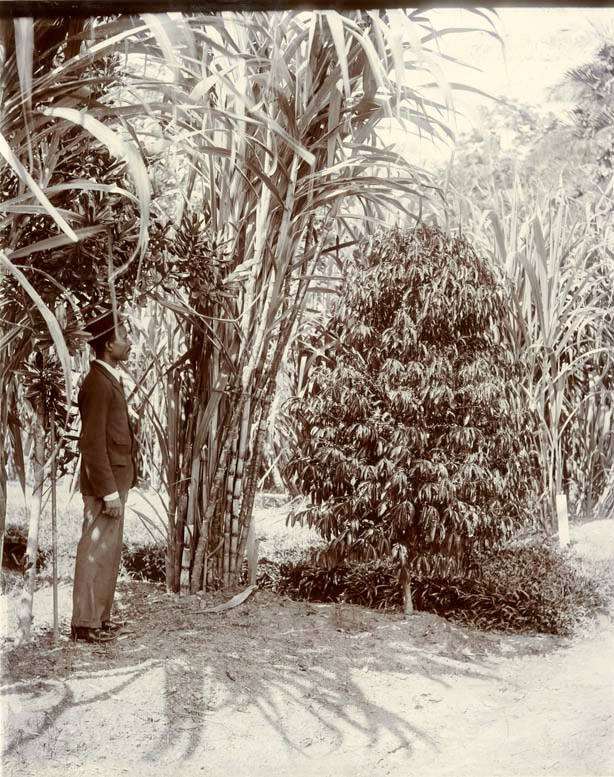

.jpg)

Discovering that stenophylla tastes like Arabica coffee is noteworthy because until now, no other of the 124 coffee species compares to Arabica in terms of its flavour. Scientifically this is compelling. We would simply not expect stenophylla to taste like Arabica, as they are not closely related, they occur on opposite sides of the African continent, and, as we shall see below, their climatic requirements are very different. They also look very different, and particularly as stenophylla has black fruits as opposed to red for Arabica and robusta. It has long been accepted that superior tasting coffee is the preserve of Arabica, grown at high elevations, in a cool-tropical climate. As we shall see below, this has now been overruled.

Hot coffee

Indigenous to Guinea, Sierra Leone and Ivory Coast, stenophylla grows in hot-tropical locations at low elevations. After collecting data for the main coffee crop species (Arabica, robusta, and Liberica), we were able to better understand their key climate requirements and compare them to stenophylla. Our results showed that stenophylla has mean annual temperature requirement of 24.9⁰C, which is 1.9⁰C higher than robusta, and a staggering 6.2–6.8 ⁰C higher than Arabica.

.jpg)

Implications and potential

Our findings have two key implications. Stenophylla makes it possible to grow a superior tasting, higher value coffee in much warmer climates than Arabica, such as in Sierra Leone. Indeed, this was the situation at the beginning of the twentieth century, when stenophylla was grown in Upper West Africa and exported to Europe at an elevated price over other coffee crop species. For the longer term, stenophylla represents a valuable breeding resource, particularly for developing the next generation of mainstream coffee crops, which will be required to tolerate the warmer and generally less suitable conditions projected under climate change.

Stenophylla coffee is amongst the 60% of wild coffee species that are threatened with extinction.

Follow the Topic

-

Nature Plants

An online-only, monthly journal publishing the best research on plants — from their evolution, development, metabolism and environmental interactions to their societal significance.

What are SDG Topics?

An introduction to Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) Topics and their role in highlighting sustainable development research.

Continue reading announcement

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in