A wireless and bioresorbable approach to temporary pain control

Published in Biomedical Research

Pain management after surgery remains one of the most persistent challenges in modern medicine. Although pain is a natural biological signal, uncontrolled postoperative pain can slow recovery, reduce mobility, and significantly diminish quality of life. For decades, medications have been the dominant solution. However, widespread reliance on pharmacological pain control has also revealed serious limitations, including systemic side effects and the risk of misuse.

As researchers, we were motivated by a simple but difficult question.

Can pain be controlled precisely, temporarily, and reversibly without drugs, rigid electronics, or permanent implants?

This question became the starting point of our work on a wireless and bioresorbable triboelectric nerve block system.

Why existing solutions are not enough

Electrical stimulation of peripheral nerves has long been recognized as a powerful method for pain control. Unlike drugs, it is reversible, fast acting, and can be spatially targeted. In particular, nerve conduction block techniques can suppress pain signals at their source rather than masking them downstream.

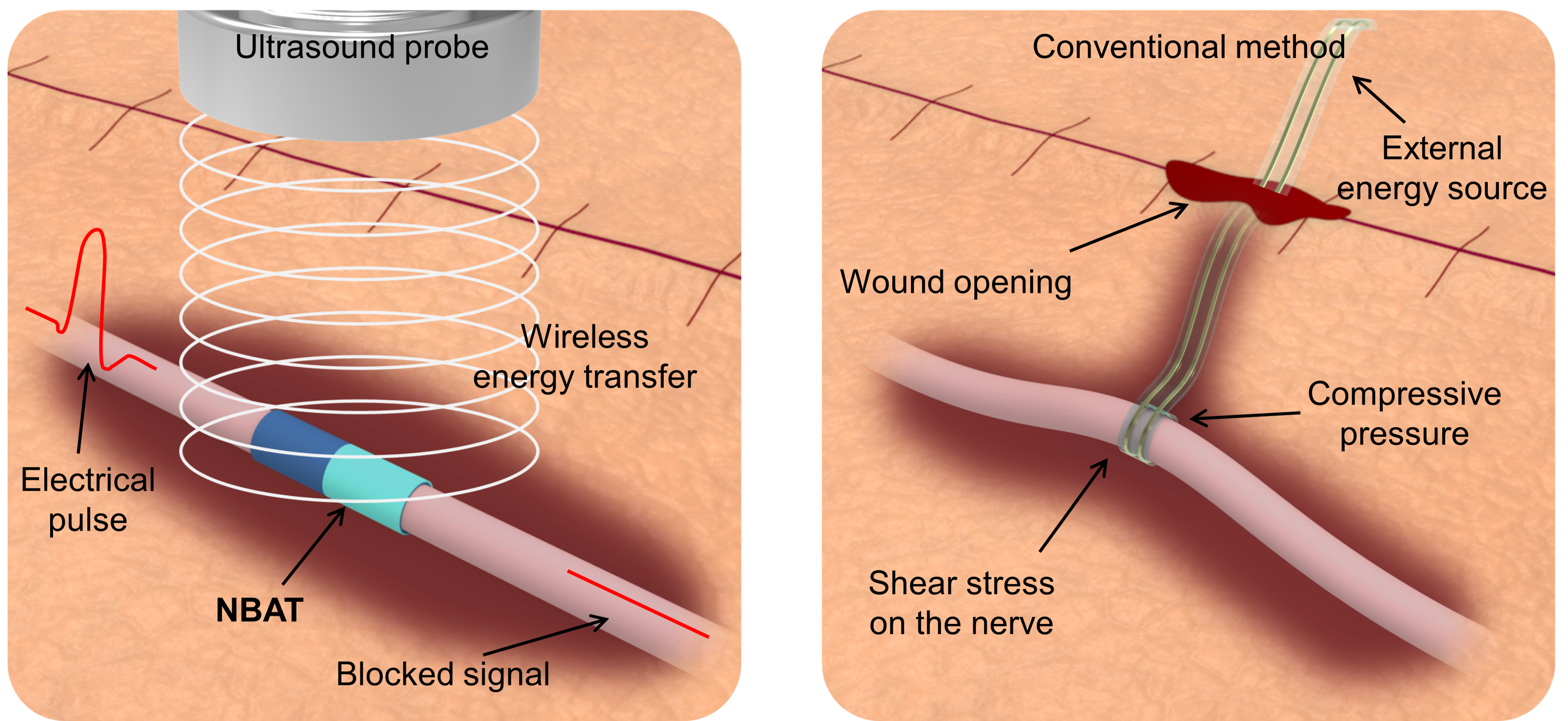

Despite these advantages, most existing non pharmacological pain control technologies share a fundamental limitation. They require wires connecting implanted components to external power sources. These wired connections introduce several problems at once. They can mechanically burden fragile nerves, interfere with wound healing, increase infection risk, and reduce stimulation stability when the patient moves. In many cases, a second surgery is also required to remove the implanted hardware.

Wireless power transfer seems like an obvious solution. However, electromagnetic based approaches typically operate at high frequencies and require bulky transmitting and receiving components. When scaled down for implantable use, efficiency drops sharply, making them unsuitable for short term pain control devices that must remain small, soft, and safe.

Rather than trying to optimize existing architectures, we decided to step back and rethink the entire configuration.

Rethinking pain control from the material level

Instead of asking how to wire power into the body, we asked whether power could be generated directly at the nerve, only when needed.

This led us to triboelectricity. When two materials with different surface properties repeatedly contact and separate, electrical charges are generated. While often associated with static electricity, this effect can also be harnessed in a controlled and repeatable way.

To activate this process inside the body, we turned to ultrasound. Ultrasound is already widely used in clinical settings and is known for its deep penetration and safety profile. In our system, ultrasound does not stimulate the nerve directly. Instead, it causes microscopic vibration of a soft polymer device wrapped around the nerve. This vibration induces alternating contact and separation between polymer layers, generating an electric field aligned with the nerve direction.

Importantly, this approach eliminates the need for metal electrodes. The nerve itself serves as part of the electrical environment. The resulting alternating electric field restricts the movement of ions near nerve membranes, preventing action potentials from propagating and thereby blocking pain signals.

A device designed to disappear

Another central goal of this work was transience. For postoperative pain, permanent implants are often unnecessary. We wanted a device that would function reliably for a limited time and then safely disappear.

We therefore built the system entirely from a bioresorbable polymer already used in medical applications. By modifying the surface chemistry of the same polymer, we created two layers with opposite triboelectric properties while preserving mechanical softness similar to that of neural tissue. The final device is thin, flexible, and monolithic, without separate electrodes, circuits, or batteries.

After implantation, the device gradually degrades over several weeks, eliminating the need for surgical removal. Throughout this process, we observed no chronic inflammation, fibrosis, or damage to surrounding nerve or muscle tissue.

What the experiments revealed

One of the most encouraging moments came during behavioral testing. In an acute nerve injury model, animals typically show reduced movement due to pain. When our device was activated by ultrasound, we observed a rapid and significant recovery of locomotion. The animals moved more freely and explored their environment without signs of motor impairment.

Electrophysiological measurements confirmed that nerve conduction was effectively blocked during ultrasound activation and recovered quickly once stimulation stopped. These results demonstrated that pain control was reversible, repeatable, and precisely controllable in time.

Equally important were the negative results. We saw no changes in gait, no long term nerve damage, and no adverse systemic effects. In many ways, what did not happen was just as meaningful as what did.

Beyond wires and conventional architectures

One of the broader implications of this work is that it challenges the conventional structure of implantable neuromodulation systems. Traditional devices are typically composed of an energy transmitter, an energy receiver, a conversion circuit, and a cuff electrode. Our system collapses this entire architecture into a single soft polymer structure that uses mechanical motion and surface chemistry to generate functional electrical effects.

This shift opens the door to new ways of thinking about implantable devices. Instead of rigid electronics that must be powered continuously, we can imagine systems that remain dormant until externally activated, perform their function, and then vanish.

Looking toward future applications

We believe this technology has particular promise when combined with emerging wearable and patchable ultrasound systems. Soft ultrasound patches that conform to the skin are already being developed for continuous imaging and monitoring. Integrating such patches with transient implants could enable precise, on demand pain control without restricting patient mobility.

While our current study focuses on postoperative pain, the underlying concept may extend to other temporary neuromodulation applications where reversibility, softness, and bioresorption are essential.

Reflections

Behind this paper lies a long process of iteration, discussion, and collaboration across disciplines. Materials science, energy harvesting, neuroscience, and clinical insight all played critical roles. Many early ideas did not work as expected, but each failure helped clarify what was truly necessary.

Ultimately, this work is not only about a new device. It reflects a broader belief that medical technology should adapt to the body rather than forcing the body to adapt to technology. If pain control can be achieved without drugs, wires, or permanent implants, even for a short time, it may help patients recover more comfortably and reduce reliance on medications.

That possibility continues to motivate our work.

Follow the Topic

-

Nature Biomedical Engineering

This journal aspires to become the most prominent publishing venue in biomedical engineering by bringing together the most important advances in the discipline, enhancing their visibility, and providing overviews of the state of the art in each field.

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in