After the Paper | Taking research from idea to impact

Published in Sustainability

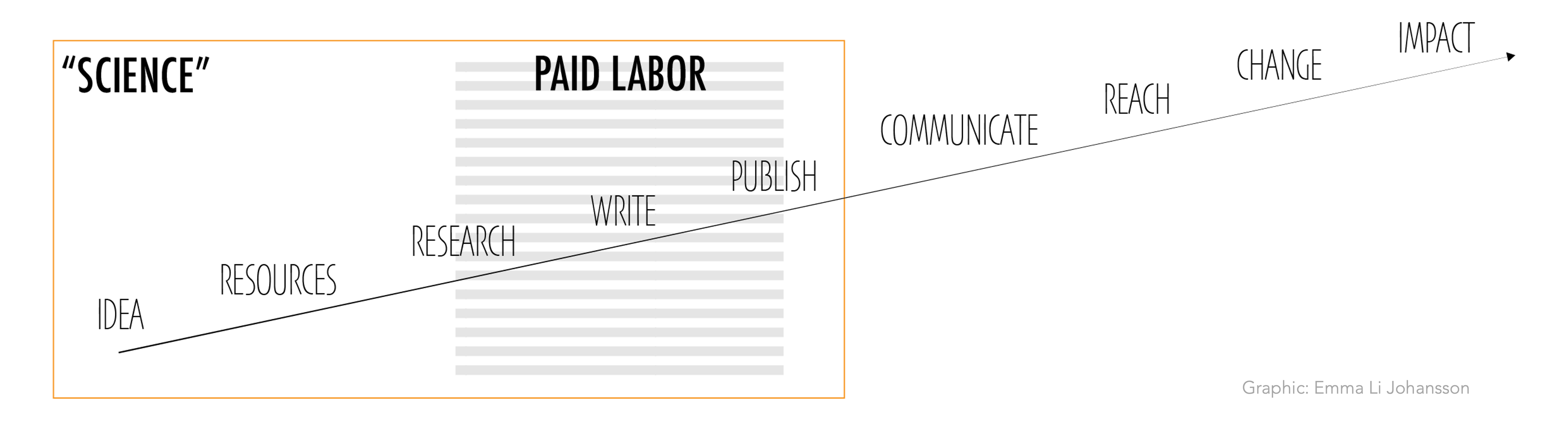

Seven steps for science communication

In September 2021, we published a Perspectives paper in Nature Energy together with Felix Creutzig, Thomas Dietz, and Paul Stern where we argued that people with high socioeconomic status play a critical role in locking in or rapidly reducing greenhouse gas emissions through five roles: as consumers, investors, role models, participants in organizations, and citizens.

Our findings achieved broad reach across media, science, and popular culture. The study received media coverage including by BBC, Grist, Forbes, Der Spiegel, and Bloomberg. The five roles were featured in the recent IPCC mitigation report and press conference. Perhaps most surprisingly, our paper attracted the attention of Netflix, who in partnership with Count Us In used our five-role framework to organize the actions on their climate action platform accompanying the movie Don’t Look Up. Kristian served as an advisor on the revision of the platform and was later thanked in a tweet by Leonardo DiCaprio, an undisputed high point in Kristian’s academic career!

Reflecting on how our findings from a scientific publication reached a broader audience, we identify seven steps that helped us communicate our science successfully:

- Starting with a research idea of broad societal interest, with a hint of controversy by focusing on the disproportionate climate influence of elites

- Working hard as an interdisciplinary team to write clear take-home messages

- Collaborating with a talented graphic designer, Emma Li Johansson, to develop visuals to communicate key messages within the paper and beyond

- Getting the paper accepted in a high-impact journal, which tends to attract more attention, and publishing open access, which tends to increase citations

- Working with the Cambridge University press office to develop a press release, which helped both our internal communications (for authors to clarify our key messages) and external communications (especially as we reached out to journalists)

- We directly pitched the story to dozens of journalists

- Writing our own communications: we co-wrote a popular science summary in New Scientist, Kristian wrote a widely shared Twitter thread, and Kim featured the work in her monthly climate advice newsletter, We Can Fix It.

Why scientists should communicate our work directly to increase impact

Academic incentives generally evaluate the “impact” of a scientific paper using metrics like journal impact factor, citation count, and perhaps the paper’s popular and social media uptake via Altmetrics. But these metrics are measures of reach, the number of people who have seen the work. They do not measure impact, which is the benefit to society of the research, or the good that researchers can do in the world. The point of communicating science is to reach the people who can benefit from it and to change their hearts or minds in some way that leads to changes in practice or policy that make the world better. Where appropriate, knowledge co-produced with diverse groups is more likely to have impact.

In our case, widely communicating our research helped the work reach more people (see Figure), including the Netflix sustainability manager who invited Kristian to contribute to the climate action platform. Our work has thus contributed to the change of informing nearly 600,000 people who have taken over 15 million climate actions, from flying less to calling a politician, resulting in about 175,000 tonnes of avoided carbon pollution. The impact of this work is the safer and more just conditions from avoided climate chaos.

In our experience, key messages and results become far more powerful and far-reaching when they are communicated directly by scientists. Effective communication requires a strategy for framing and developing messages that will reach and resonate with an audience. These are skills that scientists need to practice and cultivate. Options include science communication training, as Kim has received since 2004 through organizations such as COMPASS, and co-creating messages with communication professionals, such as university press officers.

While not every scientist wants to become a public-facing communicator, scientists often have the potential to have a wider reach than institutions, and thus to support greater impact. Partly this is because effective communication requires identifying, understanding, and engaging with your audience, which is built on time and effort in cultivating relationships. For example, Kristian’s Twitter thread on our Nature Energy study received 167,000 exposures and 5,400 engagements, whereas the institutional tweets about the paper received less than 40 engagements. Scientists will likely have more in-depth knowledge of the audience for our work; in our case, we reached out to engage in online discussion with specific readers who we thought would be interested in reading and sharing the work.

The higher response to scientists communicating our results is also because the public overwhelmingly wants to hear from scientists directly. Pew Research Center data show that scientists are the most trusted group in the United States, and widely trusted globally, to act in the public interest. Sixty percent of Americans want scientists to take an active role in policy debates about scientific issues.

Media and social media are critical channels to widen the reach of research, and thus amplify the potential benefit the research findings can have. According to Nature Energy data, over 27,000 people have accessed our scientific study. From contacting journalists who wrote about our findings, we know that at least ten times more people read news articles about the research. Some of these news readers are scientists, who might go on to read the original study and build upon it in their own research; media coverage tends to increase citation count. Other readers are business and government decision-makers, who are unlikely to read the original study; media is the primary channel to reach them. Our experience in reaching media outlets is that journalists are much more responsive to personal contact from a scientist conducting the research, who is the most familiar with and passionate about the work, rather than a generic press release about the existence of a new study.

A scientist’s best chance to achieve broad reach in communicating their research findings is often just before and after study publication. However, investing the time and effort to do this work is often at odds with academic incentives. We estimate that we spent about 40% of our total time working on the paper during the communication and outreach stages, much of it time-sensitive work around publication. We have no doubt this contribution of our time dramatically increased the reach of our work, but it was time during which we (temporarily) neglected our funded teaching and research activities. Relying on unsupported labor to achieve impact is an unsustainable approach for scientists to contribute to society.

Reality check: Universities need to support scientists doing impact work

Measuring impact is challenging but must be improved. What gets measured gets managed. Key principles for impact metrics include measuring performance towards achieving the research mission of the institution or individual, as suggested in the Leiden Manifesto for research metrics; using “baskets of indicators” to capture different aspects of research impact, paying attention to potential bias; and using a “narrative with numbers” approach to combine qualitative data and stories with complementary quantitative measures. Evaluation work is increasingly shifting from pursuing one “optimal” form of impact, or expecting to quantify the “amount” of impact from a single actor, to acknowledging different roles (like seed sower or over-the-line getter) in helping bring about social benefits. Science communication itself needs to become more evidence-based to increase its impact.

If universities want to live up to their missions and are serious about benefitting society, they need to articulate clear societal impact goals and support academic researchers doing the time-consuming work to build the relationships and skills that will increase the chances of their research having a genuine impact. We need academic positions that explicitly reward, and funding that explicitly values, recognizes, and pays for the skills and labor it takes to effectively communicate a published paper. This includes training and time for academics to increase our impact capacity, and support for professional communicators and graphic designers to co-create incisive, accurate messages to communicate. The Guidebook for the Engaged University offers a roadmap for universities to become more relevant in solving major societal problems, including best practices for tenure and promotion, supporting engagement leaders, and promoting diversity and equity in engagement work. The authors from Beyond the Academy Network argue, “Engaged scholarship is the present and future of academia… if you’re not doing engaged work, you’re behind.”

Follow the Topic

-

Nature Energy

Publishing monthly, this journal is dedicated to exploring all aspects of this on-going discussion, from the generation and storage of energy, to its distribution and management, the needs and demands of the different actors, and the impacts that energy technologies and policies have on societies.

What are SDG Topics?

An introduction to Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) Topics and their role in highlighting sustainable development research.

Continue reading announcementRelated Collections

With Collections, you can get published faster and increase your visibility.

Microgrids and Distributed Energy Systems

Publishing Model: Hybrid

Deadline: Mar 31, 2026

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in