Amino acid energetic processing leading to extraterrestrial peptides

Context of the work

The inheritance of molecular building blocks of life from extraterrestrial sources is one possible hypothesis for the origin of life. The detection of glycine in the coma of comet 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko [1] was a notable discovery, as comets are comprised of the most pristine material that is known in the solar system. It opened up the possibility of amino acids being formed in the interstellar medium and subsequently inherited into the solar system.

Laboratory-simulated formation routes for glycine under interstellar conditions have also been investigated. These formation routes have been found to be both energetic, such as through processing with UV light [2,3] or non-energetic in nature[4], early in the evolutionary stages of a dense molecular cloud. These laboratory investigations suggest that simple amino acids, such as glycine, may be widespread in space. However, the fate of glycine under astrophysical conditions, such as how it reacts when energetically processed, remains largely unexplored, with only a few groups having studied the survivability of glycine in these environments [5].

The journey

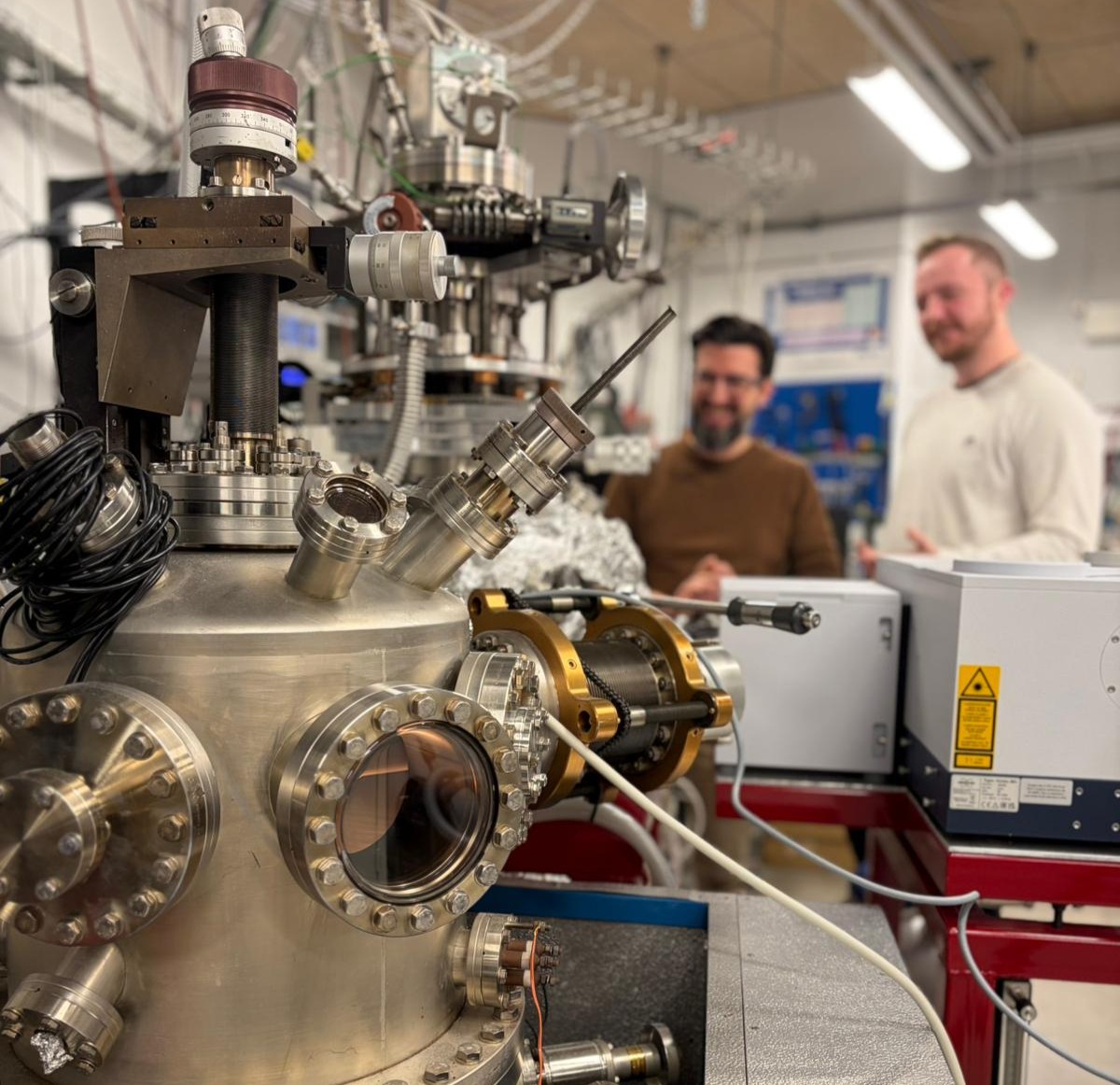

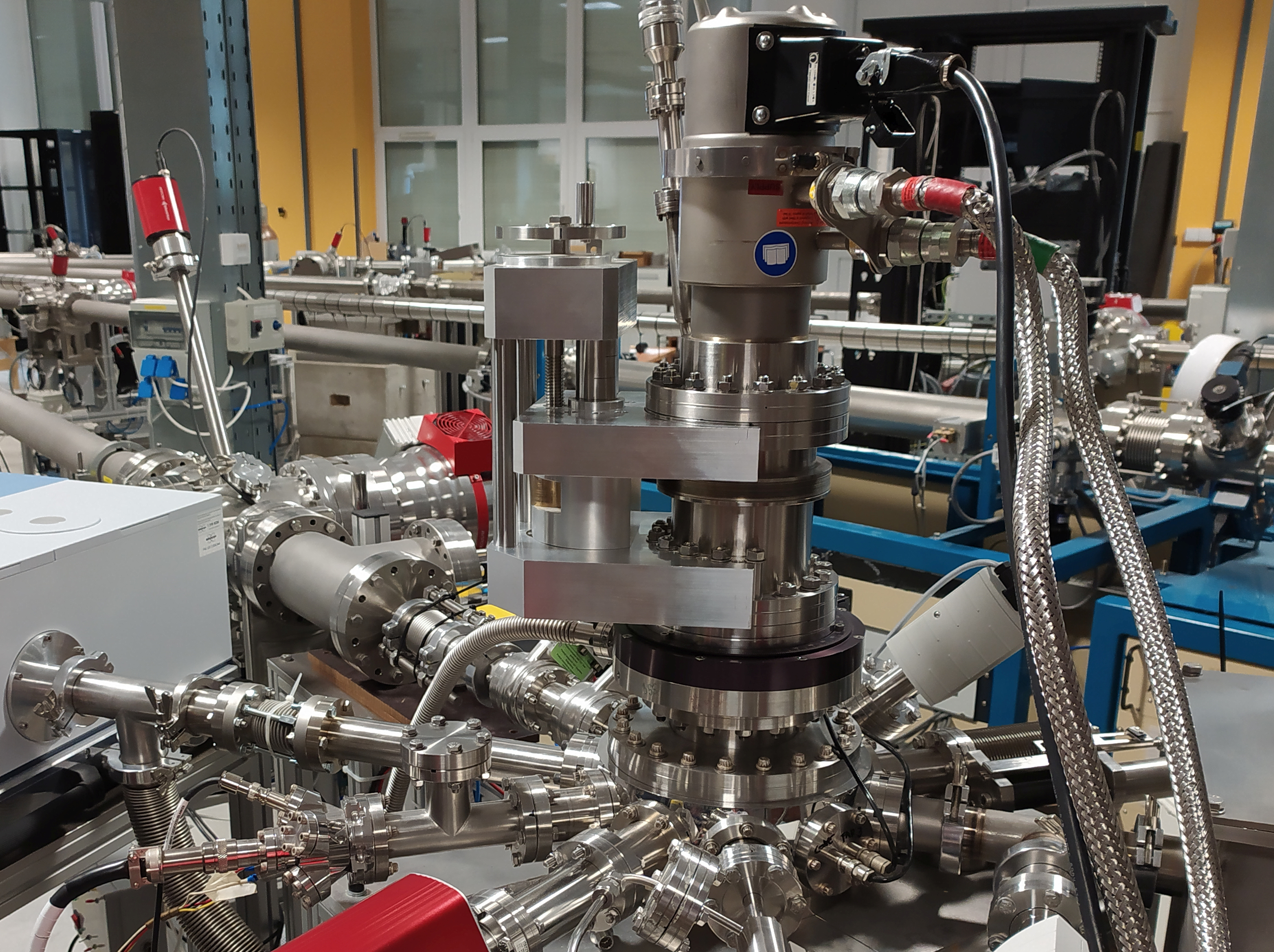

This was the scientific landscape that I encountered when I started my PhD in 2021. Having always been interested in the origin of life and how the molecular building blocks of life may have been initially formed, the question of how amino acids such as glycine may react to become more complex molecular species immediately interested me. However, the method of investigating the energetic processing of glycine under interstellar conditions eluded me. I needed to be able to have access to a source of processing that would be similar to that found in space, while also having all the necessary instrumentation to investigate what was happening to the glycine. The solution to this problem came in the form of my co-supervisor and discoverer of a non-energetic formation route to glycine [4], Associate Professor Sergio Ioppolo, who alerted me to a call for proposals at the Institute for Nuclear Research (Atomki) in Hungary. This facility contains two ultra-high vacuum chamber end stations (ICA and AQUILA) that are both connected to ion sources that would allow me to bombard glycine with high-energy protons to simulate cosmic rays and solar wind. The chambers were also equipped with instruments such as infrared spectrometers and mass spectrometers that would allow me to investigate the reactions. Armed with this knowledge, I submitted my first proposal to go and use this facility and finally investigate the energetic processing of the amino acid glycine, which was luckily accepted.

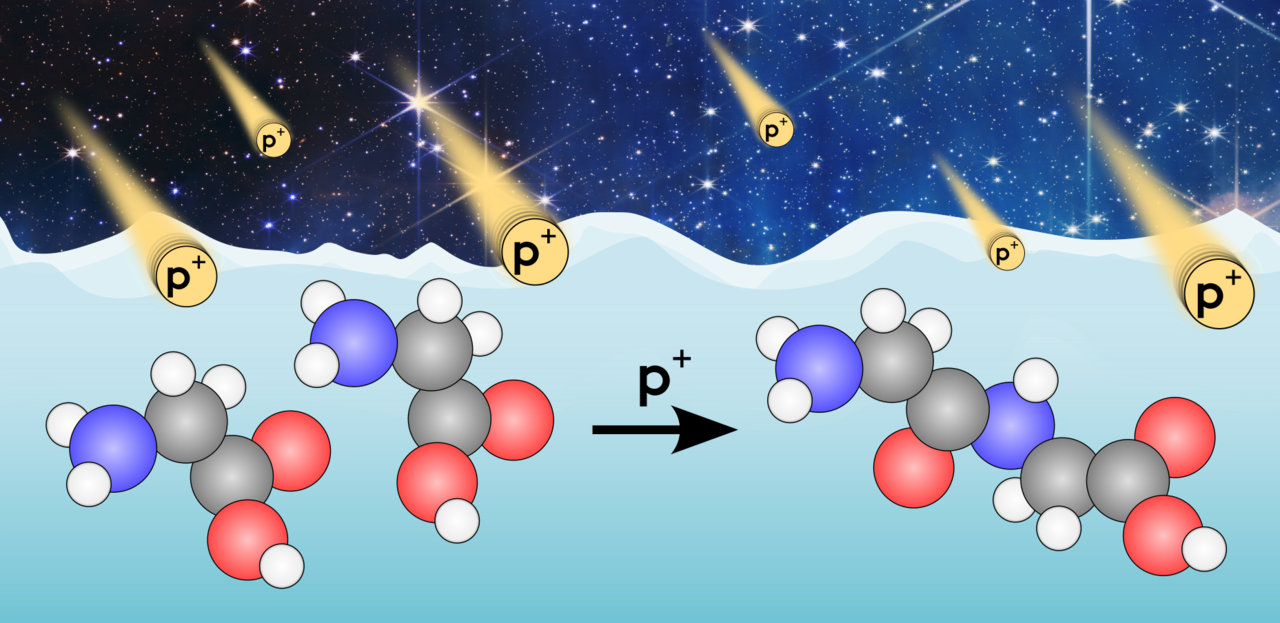

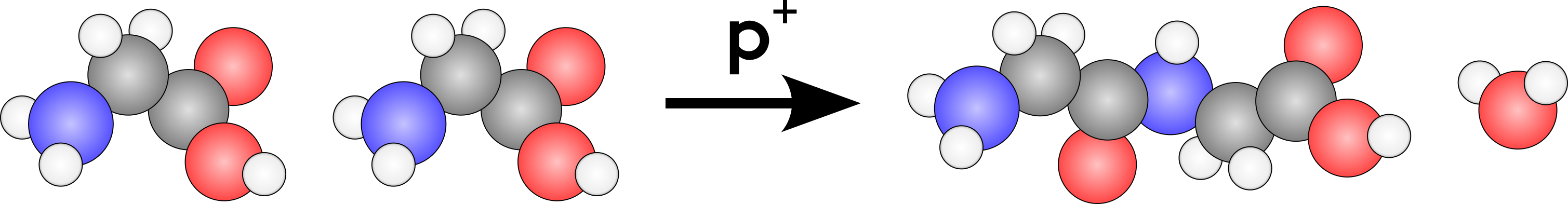

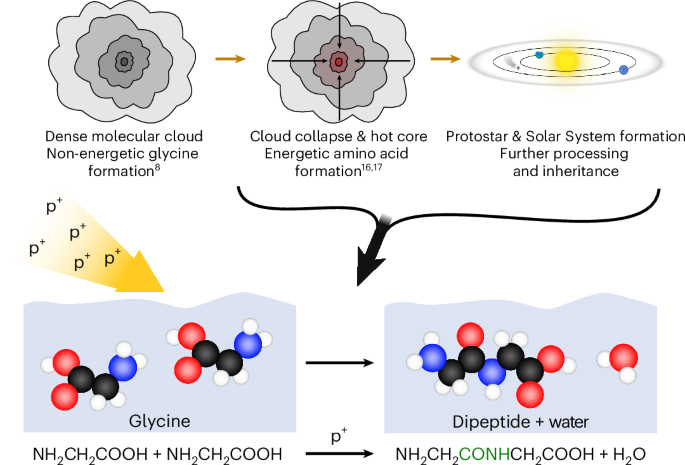

So, in the early months of 2023, I began my journey into investigating the energetic processing of the amino acid glycine. Through the help and expertise of my colleagues at Atomki, we successfully bombarded glycine with energetic protons. However, despite observing indications of reactions, such as the formation of amide bonds, there was no definitive proof that the protons had done more than just destroy the glycine molecules. This was due to infrared signals overlapping and therefore confusing, and so a different approach was required. This was the point we realised that the best way to see if there had been reactions may not be through trying to observe the biologically relevant molecules themselves, but instead the secondary products. I hypothesised that if energetic processing was making amide bonds, then this could be due to the formation of more complex molecules, such as dipeptides, which can form through condensation reactions that produce water as a secondary product. This reaction is presented in the image below. This water is what we would try to observe. The breakthrough with this was to use different isotopologues of glycine, particularly partially deuterated and fully deuterated glycine, to allow the origin of any water to be traced.

Before Christmas, I returned to a markedly colder and more festive Atomki to bombard glycine once again with protons. These laboratory experiments revealed that water had been formed both in the infrared spectra and in mass spectrometry. The deuteration of the water indicated that there had indeed been condensation reactions and, therefore, peptides were likely on the surface. I left Hungary with one final hurdle I had to overcome. It would be a challenge that I thought about over that Christmas break and well into the next year. How could I definitively show that this process did indeed form more complex molecules, such as peptides?

My solution to this problem ended up being to investigate the residue and material left after the glycine processing outside of the vacuum chamber. With the assistance of Associate Professor Carsten Scavenius, my collaborator at the Department of Molecular Biology and Genetics, Aarhus University, we could use a method called electrospray ionization mass spectrometry to investigate the molecules that remained after irradiation. This revealed that the energetic processing had resulted in the formation of a vast array of different molecules, including glycylglycine - the simplest dipeptide. It was at this point that my colleagues and I decided that we should attempt to publish this finding in Nature Astronomy, a journal that had published Sergio's groundbreaking research [4] previously, which had underpinned so much of my PhD work. Therefore, shortly before I handed in my PhD thesis in late 2025, I submitted our work to Nature Astronomy, and we are very proud to see the result of this process, which took three years of experiments, calculations, collaborations and discussions to achieve.

The implications

Our findings suggest that energetic processing of glycine in interstellar clouds, protoplanetary disks, and planetary bodies is not only a destructive process that would limit the possible complexity of molecules in space, but in fact can create many larger, more complex molecules. Many of these molecules are yet to be identified, and shows that this energetic processing of amino acids could contribute to the inventory of prebiotic molecules available for planetary accretion. This is a clear path to the formation of peptides, the building blocks of proteins, in non-aqueous space conditions found in many environments in space, and these protein building blocks could be delivered to the early Earth. This work advances our understanding of the astrochemical complexity and molecular inheritance of biologically relevant compounds with implications for the origins of life.

References

- Hadraoui, K. et al. Distributed glycine in comet 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko. Astron. Astrophys. 630, A32 (2019).

- Munoz-Caro, G. et al. Amino acids from ultraviolet irradiation of interstellar ice analogues. Nature 416, 403–406 (2002).

- Bernstein, M. et al. L. Racemic amino acids from the ultraviolet photolysis of interstellar ice analogues. Nature 416, 401–403 (2002).

- Ioppolo, S. et al. A non-energetic mechanism for glycine formation in the interstellar medium. Nat. Astron. 5, 197–205 (2021).

- Maté, B. et al. Stability of extraterrestrial glycine under energetic particle radiation estimated from 2 keV electron bombardment experiments. Astrophys. J. 806, 151 (2015)

Poster image adapted from NIRCam image of the Cosmic Cliffs - NASA, ESA, CSA, and STScI

Follow the Topic

-

Nature Astronomy

This journal welcomes research across astronomy, astrophysics and planetary science, with the aim of fostering closer interaction between the researchers in each of these areas.

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in