Evolution often works like a tinkerer, repurposing old tools to build new traits. Butterfly wings provide a striking example: they are adorned with dazzling patterns, stripes, patches, and the iconic circular rings of color known as eyespots, which can deter predators or attract mates. These eyespots are not just decorative; they play critical roles in survival and reproduction. But how do such intricate patterns arise? Do butterflies evolve entirely new genetic programs for each design, or do they cleverly redeploy existing ones?

Our recent study, published in Communications Biology, provides a surprising answer. The genes that originally shape the network of veins on insect wings, an ancient and essential trait, have been repurposed to form the colorful rings of butterfly eyespots. Around 400 million years ago, wing veins evolved through the establishment of sharp boundaries between different cells, orchestrated by a specific set of genes. Millions of years later, butterflies appear to have co-opted this same boundary-building machinery to separate the colored rings of eyespots. In other words, the same developmental logic that organizes structural elements of the wing was reused to pattern pigmentation.

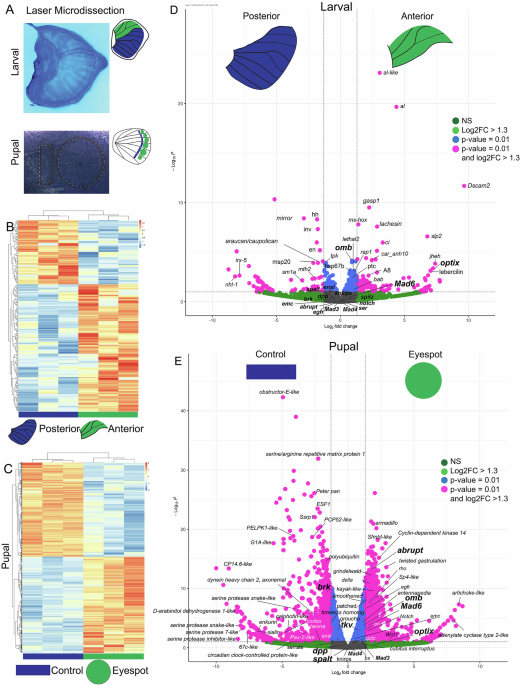

To test this idea, we combined several cutting-edge approaches. First, we used laser microdissection to isolate tiny sections of developing wing tissue at different developmental timepoints. This technique allowed us to precisely capture the regions that are essential for vein-specific signaling and the region that would later become the eyespot. We then performed RNA sequencing on these samples to determine which genes were active in each region. By comparing gene expression patterns across different parts of the developing wing, we could identify candidates likely involved in eyespot ring formation.

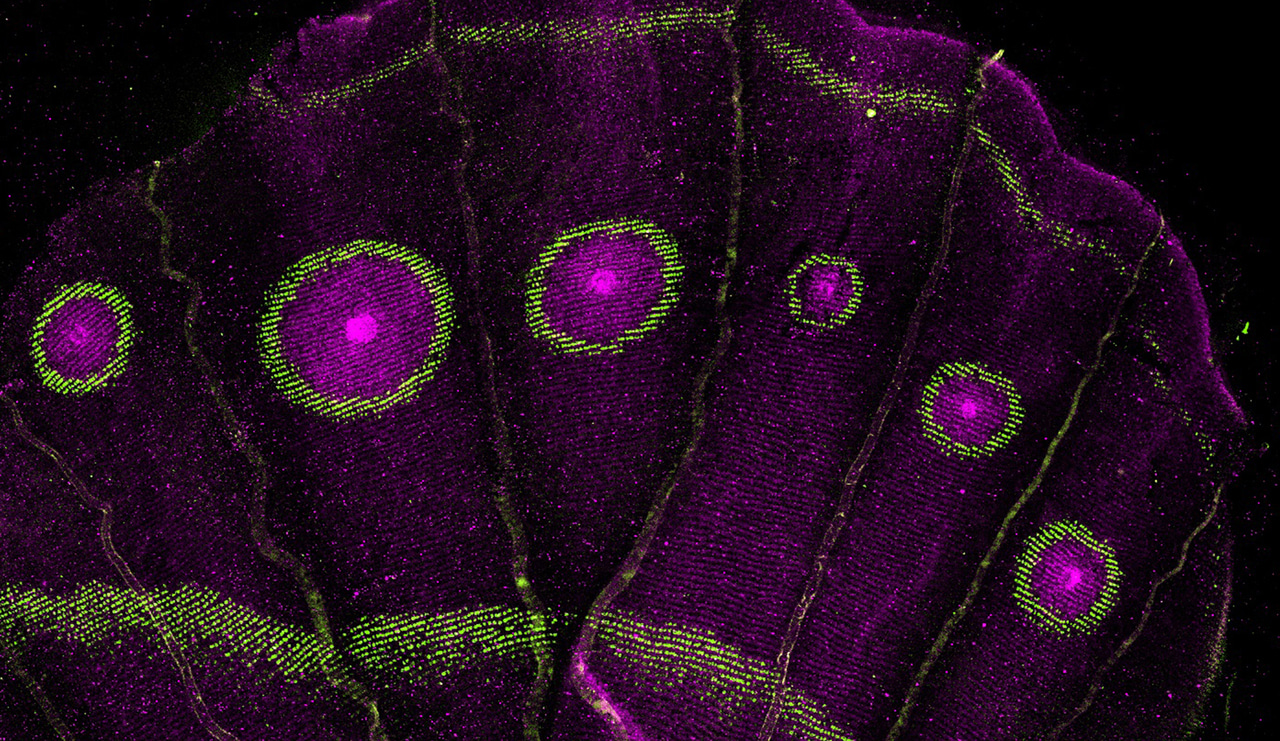

Next, we mapped the spatial expression of these candidate genes using fluorescent in situ hybridization and antibody staining. These techniques revealed exactly where each gene was turned on within the wing tissue. Interestingly, many of the same genes that position wing veins were active in the concentric rings of the eyespots, suggesting that butterflies were indeed repurposing an ancient genetic program rather than inventing a new one.

Finally, we tested the function of key genes using CRISPR-Cas9 gene editing. By selectively disrupting individual genes, we could observe how their absence affected eyespot formation. Knockouts often led to clonal patches of missing rings, confirming that these genes are crucial for defining the boundaries between different colors in the eyespot. These experiments provided direct evidence that the ancient vein-patterning network had been redeployed in a completely new developmental context.

Our results support a broader principle in evolution: new traits often arise not from entirely new gene networks, but from older networks being switched on in different contexts or at different developmental times. This creative recycling of genetic toolkits has produced striking diversity in nature. Similar examples include beetle horns, treehopper helmets, and even flower petals, where ancient genes are repurposed to build new features. In butterflies, this repurposing has allowed evolution to generate eye-like patterns that are both visually stunning and functionally important.

Beyond revealing how eyespots evolve, our study highlights how deep evolutionary history constrains and guides innovation. Rather than inventing completely novel solutions, evolution often works by tweaking and redeploying existing developmental programs. This principle helps explain why some traits appear repeatedly in nature, albeit in different forms or contexts, and why seemingly novel structures often have very ancient genetic foundations.

Looking ahead, this work opens exciting possibilities for understanding the evolution of other complex traits. By combining spatial transcriptomics, gene editing, and imaging, researchers can trace how ancient networks have been co-opted across different species and traits. The findings also underscore the power of using multiple complementary approaches to uncover developmental logic that would otherwise remain hidden.

Follow the Topic

-

Communications Biology

An open access journal from Nature Portfolio publishing high-quality research, reviews and commentary in all areas of the biological sciences, representing significant advances and bringing new biological insight to a specialized area of research.

Related Collections

With Collections, you can get published faster and increase your visibility.

Signalling Pathways of Innate Immunity

Publishing Model: Hybrid

Deadline: Feb 28, 2026

Forces in Cell Biology

Publishing Model: Open Access

Deadline: Apr 30, 2026

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in