An interview with Dr. Goylette Chami

Published in Social Sciences

Explore the Research

sciencedirect.com

sciencedirect.com

ScienceDirect

About ScienceDirect Shopping cart Contact and supportTerms and conditionsPrivacy policy

Please tell us about your research interests.

Over one billion people are afflicted with at least one neglected tropical disease. The most common neglected tropical diseases include schistosomiasis (‘snail fever’), soil-transmitted helminths (‘gut worms’), lymphatic filariasis (‘elephantiasis’), and onchocerciasis (‘river blindness’). These diseases are caused by parasitic worms and are called ‘neglected’ in that vulnerable, impoverished populations—most often from low-income countries—are affected. The largest treatment programmes globally (mass drug administration) provide blanket preventive chemotherapies, either annually or biannually, in at least 72 countries. Mass drug administration is possible due to the large-scale donations of medicines by the pharmaceutical industry and international aid (predominantly from the U.K. and U.S.A). The ability of mass drug administration to control disease onset and progression depends largely on the social-ecology of the treated communities. Environmental factors determine transmission risks; not all individuals who need treatment are reached and morbidities caused by neglected tropical diseases have complex aetiologies.

My research aims to improve the effectiveness of mass drug administration. I focus on the treatment of schistosomiasis in rural, poor villages of sub-Saharan Africa. This disease is caused by a parasitic blood fluke and transmitted via contact with contaminated freshwater sources. I collaborate closely with the Uganda Ministry of Health to design new treatment packages and to identify behavioural interventions that will reduce the burden of schistosomiasis. New treatment packages are needed because schistosomiasis, as well as any other neglected tropical disease, does not exist in isolation. It is coendemic with several other major contributors to morbidity and mortality in low-income countries including malaria, diarrhoeal diseases, and so on. However, mass drug administration is not necessarily integrated with other ongoing treatment initiatives. Additionally, behavioural interventions are needed because limited access to safe water and adequate sanitation enables the persistence of most neglected tropical diseases.

What has your journey been to this point?

I have become an infectious disease epidemiologist of tropical medicine through a rather unusual journey. My undergraduate studies were in economics and political science (double major) at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, US. I had a keen interest in development economics and pursued semesters abroad in Hungary and Syria. But, I became drawn to the medical sciences as a way to study absolute poverty. You must first be alive to do anything else; without good health, individuals cannot work productively or fully exercise their economic and political rights.

With a scholarship from the Jack Kent Cooke Foundation, I completed an MPhil then PhD at the University of Cambridge, where I worked across departments bridging economics with pathology. First, I applied game theory (the study of strategic decision-making and its consequences) to understand how to reduce the transmission of diarrhoeal pathogens in Uganda. Individuals in low-income areas often share freshwater sources, for example by retrieving drinking water from a local lake, so one person’s actions (such as openly defecating in the lake) affect the risk of another user of the lake getting infected.

|

| Paired adult schistosomes. Female in red, male in blue.* |

For my PhD, I had two really supportive supervisors: Prof. Andreas Kontoleon (a development and environmental economist) and Prof. David Dunne (an immunologist and parasitologist), and several fantastic collaborators: Dr. Narcis Kabatereine and Dr. Edridah Tukahebwa from the Uganda Ministry of Health, Prof. Alan Fenwick from Imperial College London, and Prof. Erwin Bulte from Wageningen University. With them, I fully embarked on fieldwork in Uganda, setting up a study of over 20,000 people in rural villages of Eastern Uganda to improve the treatment of parasitic worms through mass drug administration, and using statistical learning and network analysis techniques. With a field project of this size, we did not have the option of a redo if the study proved uninformative!

|

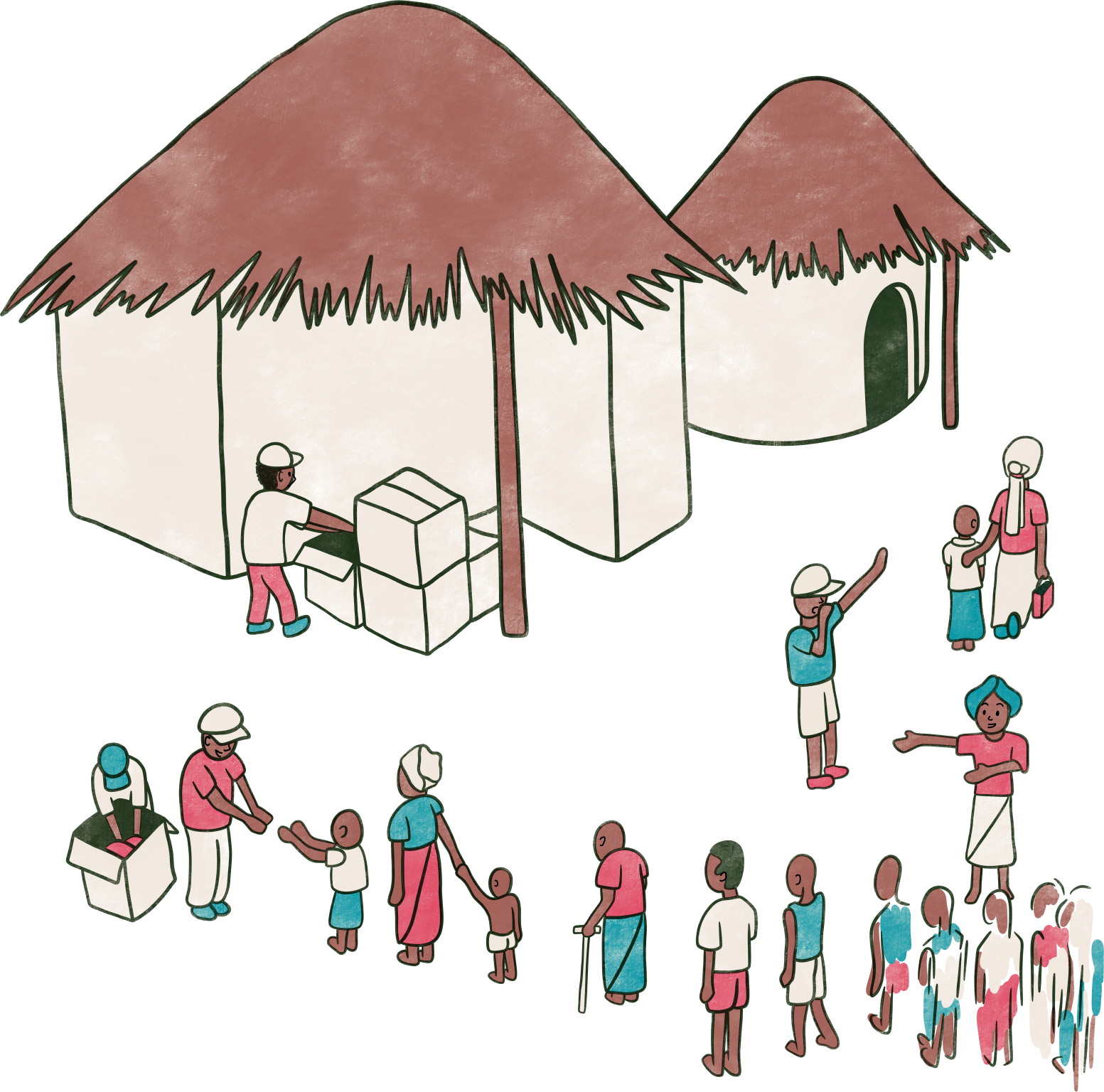

| Representation of community medicine distribution.* |

We identified predictors of treatment likelihood and delved into the biosocial determinants of coinfections. Our results have influenced national treatment policies and informed international initiatives on neglected tropical diseases. For example, World Health Organization treatment guidelines for schistosomiasis indicate that at least 75% of individuals must be treated to control disease. But, these guidelines assume that the untreated 25% are missed randomly. If the most heavily infected individuals—as we showed—are within the missed 25%, then morbidity control through mass drug administration can be undermined. We also found that the individuals missed for treatment during mass drug administration were from marginalized groups of low socioeconomic status. This emphasized that communities are not homogeneous and social factors are important predictors of treatment effectiveness.

What made our study a success was first and foremost the strong partnerships with local Ugandan collaborators. Also, combining data-driven, computational approaches with clinical outcomes helped streamline methods for evaluating mass treatment programmes, in particular by leading to new ways of handling complex data. In addition to my supervisors and collaborators, my mentors, especially Prof. David Molyneux from the Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine, played a key role in ensuring my work was feasible/practical for policy while supporting me to pursue ambitious research aims. Reconciling these two objectives is a key ongoing challenge of my career.

|

| Social network.* |

After my PhD, I stayed at Cambridge and continued research in Uganda, thanks to an Isaac Newton Trust Fellowship, Wellcome Trust-Cambridge Centre for Global Health position, and Junior Research Fellowship in Medical Sciences (King’s College Cambridge). During these years, I expanded the Uganda study, became more involved with building scientific capacity in sub-Saharan Africa and outreach in the U.K., and grew my network with policymakers, NGOs, and pharmaceutical companies. I am enthusiastic about outreach, for example, the illustrations of my research interests included in this article are a result of collaborating with students at the Cambridge School of Visual and Performing Arts. I hope to use these images, which are part of a larger series, for health education campaigns in Uganda and for UK outreach initiatives to inspire disadvantaged students to enter STEM subjects.

My research programme led me to join the Big Data Institute (BDI) and Nuffield Department of Population Health (NDPH) at the University of Oxford in July 2019. Here I am setting up a research group focused on the access to medicines for neglected tropical diseases, and the assessment of clinical consequences of coinfections with schistosomiasis and its social determinants. We will apply statistical/machine learning to primary data collected in our field studies while setting up further collaborations in Uganda and elsewhere in sub-Saharan Africa. In BDI and NDPH, there is a wealth of expertise for running large epidemiological cohorts, clinical trials, and applying machine learning to medicine. So, I am excited to develop new collaborations here and to see what the future holds for pushing the boundaries of my research.

Can you speak to any challenges that you had to overcome?

I have been immensely privileged in my upbringing and education. Though, I did have a very difficult period in my life where I took time off after my MPhil degree to take care of my terminally ill mother. When I returned to begin my PhD at Cambridge, grief hit and I struggled to readjust back to student life. My research was a way to overcome these challenges. I learned to become incredibly, perhaps narrowly, focused on research and became more ambitious in the projects I proposed in hopes of helping others live longer, more healthy lives.

What are your predictions for your field in the near future?

Mass drug administration is a great example of how advocacy, philanthropic contributions, and rapid-impact interventions can address causes of early mortality for the world’s poorest individuals. Annual treatment is now available for over one billion people who otherwise would not have access to medicines for neglected tropical diseases. Yet, these programmes are largely dependent on medicine donations from pharmaceutical companies and run predominantly as scheduled campaigns, meaning that donated medicines are not currently available within local health centres. With universal health coverage as a key priority of the World Health Organization, pressing questions remain for the treatment of neglected tropical diseases. How may individuals be treated in the absence of medicine donations and mass drug administration? How might we integrate separate disease treatment programmes, e.g. neglected tropical diseases and malaria? What is the role of local communities in managing their own health?

There also is a need to apply emerging innovations in machine learning to neglected tropical disease settings. As we move towards potential pathogen elimination, the biosocial context of an individual becomes increasingly important to target factors predicting pathogen exposure. Preventing reinfections (reducing transmission) will become a key priority as opposed to controlling morbidity (reducing infection intensity). To fully account for the biosocial context of an individual and to design appropriate interventions, advanced statistical learning methods are needed that can handle high data complexity. Thus far, the Global Atlas of Helminth Infections has applied advanced spatial methods to more accurately project geographical distributions of neglected tropical diseases based on the local ecology and ongoing intervention programmes. What is now needed is a granular look into the social determinants of infection risk and disease progression.

You can follow Goylette at https://www.bdi.ox.ac.uk/Team/goylette-chami

Head photo credit: Dr. Nicholas Bell.

* Illustrations by Kester Matine, Goi Shinyee and Sam Race, from:

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in