Are WELL Building Standard S02 Sound Levels Too Permissive of Low Frequency Noise? Addressing the LFN in the Room

Published in Bioengineering & Biotechnology

Introduction

The WELL Building Standard v2 Sound Concept aims to bolster occupant health and well-being through the identification and mitigation of acoustical comfort parameters that shape occupant experiences in the built environment. WELL Standard S02 prescribes maximum thresholds for ambient background noise that correspond to optimal levels of interior and exterior noise exposure (IWBI, WELL v2™, 2023). While the intent of WELL Standard S02 is to achieve desired ambient noise levels such that HVAC, exterior noise intrusion or other noise sources do not impact occupant health and well-being, compliance with the Standard may allow for permissible levels of low frequency noise (LFN) that are deleterious to health, negatively affecting both auditory and non-auditory outcomes (Alves, J.A., Paiva, F.M., et al., 2020). We explore the WELL Standard S02 here in the context of LFN and health impacts and suggest revisions to the Standard’s allowable levels of average and maximum noise measures.

Background

All spaces have some degree of ambient background noise from HVAC equipment, exterior sources (e.g., traffic, outdoor equipment, pedestrians) or other building services. When these noise sources exceed comfortable levels, the space may not function as intended. For instance, elevated levels of background noise can impact the perception of public address systems and diminish the perception of spoken words, which reduces critical listening ability and task performance. Studies indicate that employees are unable to habituate to noisy office environments over time and office noise, with or without speech, can create stress and disrupt performance on more complex cognitive tasks (e.g., memory of prose, mental arithmetic). In adults, exposure to traffic noise can lead to complications with the cardiovascular system, diabetes, hypertension, stroke, depression and high blood pressure. For children, chronic aircraft noise exposure impairs reading comprehension, mental arithmetic and proofreading. In both industrial and community studies, road traffic noise exposure is related to raised catecholamine secretion levels in urine, indicating an increased stress level in subjects exposed to such noise (IWBI, WELL v2™, 2023).

While our understanding of the biological pathways through which environmental noise adversely impacts health is still developing, it is known that certain components of noise are more harmful than others, particularly low frequency noise (LFN<200 Hz, typically)(Leaffer, D., et al., 2023). Chronic exposure to LFN has been linked to a variety of adverse health impacts, including decreased heart rate variability (Walker, et., al., 2016), sleep disturbance, cortisol level disruption (Waye, K.P., et al., 2003), and other stress indicators (e.g., irritability, anxiety, tiredness) (Verzini, et., al, 1999). In the field of occupational health, there are several studies which cite that LFN is an agent that interferes with the performance of work tasks (Waye, K.P., Bengtsson, J., et al., 2001).

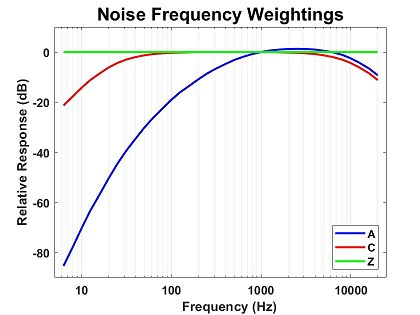

Noise exposure guidelines from both the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency and the World Health Organization utilize A-weighted noise exposure metrics, which more heavily weight frequencies between 2000 and 5000 Hz (Figure), and thereby discount lower frequencies (Branco and Alves-Pereira, 2007). A recent meta-study of LFN and health effects reinforces that the A-weighting filter is not ideal to evaluate the non-auditory effects of low-frequency noise (Alves, et al., 2020). Ascari et al. (2014) affirm that models of A-weighted sound are not appropriate to evaluate the contribution of Low Frequency Noise to the soundscape (Ascari, et. al, 2014). De-emphasizing LFN content by A-weighting can lead to underestimation of potential harm from physical and psychological effects associated with frequency content and other characteristics of sound not captured by A-weighted metrics (Waye, K.P., 2011). The difference, ∆ between C-weighted (nearly independent of frequency) noise measures (Figure), commonly expressed as dBC minus dBA, provides crude information about the presence of low frequency components in noise (Roberts, 2010).

Methods

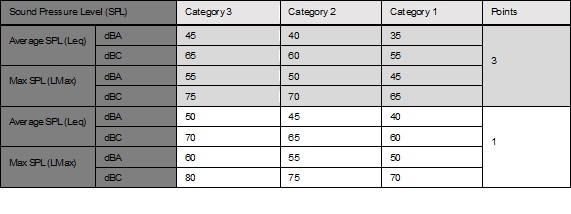

The WELL Building Standard v2 Sound Concept S02 specifies a permissible differential between average sound pressure levels (SPL) (Leq) and maximum SPL (LMax) for A-weighted (dBA) v. C-weighted (dBC) (Table) equal to 20 dB, for each of the following dwelling uses: Category 1 -areas for conferencing, learning or speaking; Category 2 -enclosed areas for concentration; Category 3 -open areas for concentration, spaces with PA systems, and areas for dining. For each metric, background noise levels are measured over a short duration for both A- and C-weightings. To earn optimization points on the WELL project scorecard, the average and maximum sound pressure levels may not exceed the thresholds listed (Table):

Discussion

Is the dBC - dBA 20 dB differential (Table) too permissive of Low Frequency Noise (LFN) in these categories? The difference, ∆ between C- and A-weightings has been considered as a predictor of noise annoyance and is an indication of the amount of low frequency energy in the noise (Broner, 1979; Broner and Leventhall, 1983; Kjellberg et al., 1997). If the difference, ∆ is greater than 20dB, there is the potential for a low frequency noise problem (Leventhall, H.G., 2003). In Germany, ∆ C- minus A-weighting >20 dB is used as an initial indication of the presence of low frequency noise and the need to conduct further investigations. (Leventhall, 2003). Kjellberg and colleagues (1997) have suggested that when ∆>15 dB, an addition of +6 dB to the measured A-weighted level is a simple procedure for addressing noise annoyance. If ∆>10 dB the World Health Organization (1999) recommends that a frequency analysis of the noise be performed. Blair et al. (2018) found that continuous weighted noise levels above 50 dBA can have effects on health, such as increasing the risk of cardiovascular disease and hypertension. Average A-weighted (dBA) levels in WELL Standard S02 meet this threshold (Table). Blair et al. also found that low-frequency noise levels exceeding the recommended level of 60 dBC caused nausea and headaches in an occupational health study (Blair et al., 2018). Half of the WELL Standard S02 permissible average C-weighted levels exceed this 60 dBC threshold, currently.

Leventhall’s (2009) review of low frequency noise and its effects leaves some unanswered questions towards which future work might be directed. Such questions posited are: Can fluctuations in the background noise level turn a [low frequency] noise which may have an average level below the hearing threshold of a listener into a nuisance? Does the way in which we measure low frequency noise hide some of its disturbing or nuisance-related characteristics? Considering the normal distribution of the hearing threshold, why are there not more complaints of low frequency noise (Leventhall, 2009).

Recommendations

The noise and health literature supports our recommendation herein to lower the average and maximum Sound Pressure Levels (SPL) C-weighted noise levels by an additional -5 dBC. This would in turn lower the permissible differential between average SPL (Leq) and maximum SPL (LMax) for A-weighted (dBA) v. C-weighted (dBC) from 20 dB as specified in WELL Standard S02 to a more conservative difference of 15 dB. This is supported by Blair, et al. (2018), who recommend if the fluctuation in dBC levels are substantial (±5 dBC), the low frequency noise criteria should be reduced by -5 dBC, to minimize health impacts from low-frequency noise.

Possible solutions to achieve this goal include control of interior noise sources by selecting HVAC equipment with lower sound ratings and by designing the system to reduce sound within ducts. Exterior noise can be controlled by providing sound reduction at the building façade, windows and any exterior penetrations. In both cases, these sound sources are easier to control when considered at the earliest possible stages of design (IWBI, WELL v2™, 2023).

Conclusions

Noise and health exposure studies support decreasing the WELL Building Standard v2, Sound Concept Standard S02 average and maximum Sound Pressure Levels (SPL) C-weighted noise levels by an additional -5 dBC. The proposed reduction from ∆C (dBC) minus A-weighting (dBA) of currently 20 dB to 15 dB across all use and occupancy Categories 1 through 3 is recommend for optimal protection of occupants from levels of low frequency noise (LFN<200Hz) that are deleterious to health, and negatively affect both auditory and non-auditory outcomes. It’s time to address the LFN in the room; the -5 dBC reduction should get us there.

References

-

International Well Building Institute (IWBI), WELL Building Standard v2™, 2023

-

Alves Araújo J., Paiva, F.M., et al. "Low-frequency noise and its main effects on human health—A review of the literature between 2016 and 2019." Applied sciences 10.15 (2020): 5205

-

Leaffer DJ, Suh H, Durant JL, Tracey B, Roof C, Gute DM. Long-term measurement study of urban environmental low frequency noise. J Expo Sci Environ Epidemiol. 2023 Sep 11. doi: 10.1038/s41370-023-00599-x

-

Walker, E., Brammer, A., et al., Cardiovascular and stress responses to short-term noise exposures—A panel study in healthy males, Environmental Research, Volume 150, 2016.

-

Waye, K. Persson. Effects of Low Frequency Noise on Sleep. Noise and Health 6(23):p 87-91, Apr–Jun 2004.

-

Verzini AM, Frassoni CA, Ortiz AH. A field study about the effects of low‐frequency noise on man. J Acoustical Soc Am. 1999;105:942–2Waye, K.P.; Bengtsson, J.; Kjellberg, A.; Benton, S. Low frequency noise “pollution” interferes with performance. Noise Health 2001, 4, 33–49].

-

Branco NAC, Alves-Pereira M, Araújo A, Reis J. Environmental Vibroacoustic Disease–an Example of Environmental Low Frequency Noise Exposure. Sound Vib. 2005;11:14.

-

Ascari E, Licitra G, Teti L, Cerchiai M. Low frequency noise impact from road traffic according to different noise prediction methods. Sci Total Environ. 2015;505:658–69 (2015).

-

Waye KP. Effects of Low Frequency Noise and Vibrations: Environmental and Occupational Perspectives, in Encyclopedia of Environmental Health, Elsevier, 2011, pp. 240–53.

-

Roberts C. Low frequency noise from transportation sources. In Proceedings of the 20th International Congress on Acoustics. Sydney, Australia; 2010, pp. 23–27.

-

American Standard ASA Z24.2. American National Standard for Sound Level Meters (1936).

-

Broner, N., The effects of low frequency noise on people—A review, Journal of Sound and Vibration, Vol. 58, Issue 4, 1978.

-

Broner N, Leventhall, HG. A Criterion for Predicting the Annoyance Due to Lower Level Low Frequency Noise. Journal of Low Frequency Noise, Vibration and Active Control. 1983;2(4):160-168Leventhall, G. ‘Low Frequency Noise and Annoyance,”, Noise & Health, vol. 6., (2004).

-

Kjellberg, Anders, Tesarz, Mari, et al., Evaluation of frequency-weighted sound level measurements for prediction of low-frequency noise annoyance, Environment International, Volume 23, Issue 4, 1997.

-

Leventhall G, Pelmear P, Benton S. A review of published research on low frequency noise and its effects. University of Westminster, UK. Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs; 2003.

-

World Health Organization (1999). Hurtley C, World Health Organization. Night noise guidelines for Europe. Copenhagen, Denmark: World Health Organization Europe; 2009. Eds.

-

Blair, B.D., Brindley, S., Dinkeloo, E. et al. Residential noise from nearby oil and gas well construction and drilling. J Expo Sci Environ Epidemiol 28, 538–547 (2018).

-

Leventhall G. Low Frequency Noise. What we know, what we do not know, and what we would like to know. Journal of Low Frequency Noise, Vibration and Active Control. 2009;28(2):79-104

Follow the Topic

-

Journal of Exposure Science & Environmental Epidemiology

This journal aims to be the premier and authoritative source of information on advances in exposure science for professionals in a wide range of environmental and public health disciplines.

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in