Behind Success or Failure: The Importance of Individual Attendance Data in Analyzing International Climate Change Negotiation

Published in Social Sciences and Law, Politics & International Studies

As the global temperature is soaring to record highs, securing summer 2024’s place as the hottest summer globally “since the worldwide records began in 1880,” it is becoming clear that Planet Earth is increasingly deviating from sustainable weather, temperature, and climate patterns. To this end, researchers, practitioners, and activists continue to outline important evidence linking these trends to human factors—all while raising broader awareness about the climate change problem and calling for action. Yet, given the continued inaction over many of climate change’s gravest challenges, it’s also important to think more deeply about the global cooperation barriers that are preventing meaningful climate action amidst this increasing body of evidence for climate change and its anthropogenic sources.

To be sure, there is no question that scientific breakthroughs have contributed to the advancement of numerous global climate change solutions. However, success in the adoption and implementation of these solutions depends in large part on international actors who fall outside of the immediate scientific community. These former actors, including national governments, corporations, and non-governmental organizations, each play unique roles in climate change cooperation, especially regarding mobilizing resources, fostering intergovernmental cooperation, and pushing for globally consistent policy decisions. In this sense, Conferences of the Parties (COPs) to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) represent the primary venue where these governmental and non-governmental actors coordinate and advance global achievements. These COPs, with a varying number of participants averaging at around 11,000 per modern COP, occur on an annual basis and bring together diverse groups of leaders, governments, and organizations who together work towards developing and implementing global climate policies. As such, the cooperation dynamics underlying the UNFCCC’s COPs is an area of particular interest for understanding the successes and failures of global progress on climate change cooperation.

However, scientific data on COPs and COP cooperation is severely limited especially as it relates to the depth and breadth of COP participation. This limits our abilities to study and understand the role of individual attendance characteristics in collective negotiation outcomes. Addressing this limitation, our recently published dataset, covering all annual UNFCCC meetings (including COPs and their precursors) over the last 32 years, includes comprehensive and nuanced information on individual attendees at each respective COPs. This information encompasses individuals’ names & honorifics, the organization that each individual attended on behalf, individual job titles, linked divisions & other affiliations, and additional details. This data accordingly provides a unique opportunity for researchers and practitioners to understand nuanced attendance patterns across the UNFCCC’s COPs—and the role that these patterns may play in cooperation breakthroughs and setbacks at the UNFCCC’s annual international climate negotiations.

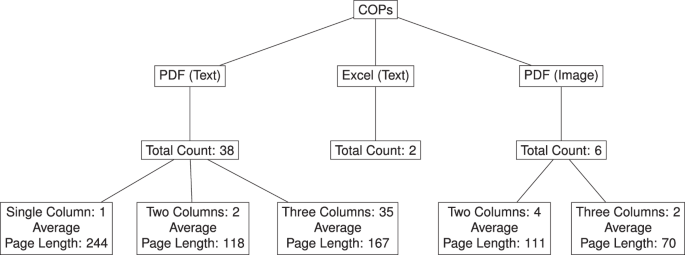

The accompanying data descriptor article Individual Attendance Data for over 30 Years of International Climate Talks authored by Blinova, Emuru & Bagozzi (2024) provides a detailed description of the data extraction process and variable details associated with the data described above. As such, it makes two important contributions—one methodological and one substantive. In the former case, the article provides a detailed framework, codebase, and overview of the automated tools needed for extracting larger heterogeneous attendance records from international negotiation records, which are commonly stored in diverse PDF formats. Substantively, the article in turn demonstrates the richness of UNFCCC COP attendance data, offering an important starting point for theoretical work into the drivers and consequences of COP attendance patterns.

On the latter point, the dataset offers a unique opportunity for both qualitative and quantitative scholars to understand previously un(der)explored dimensions of the UNFCCC’s climate talks. For instance, these data may further enable qualitative scholars to study or cross-reference the positional power of individual COP participants and related dimensions to authority—either over time or across a single COP’s participants. The data may likewise serve as a unique starting point for identifying social networks among the UNFCCC COPs’ overlapping participants—providing a foundation for in-depth case studies of specific groups or organizations, or offering an entry-point to large-N network analyses. The data also offers a variety of possibilities relating to the consideration of gender and representation patterns over time, across the positions of authority held by individual attendees, and across distinct types of attending groups. Finally, and across any of the above dimensions, the recorded names of attendees allow for an understanding of repeat attendance over COPs and time—a potential contributor to cooperation success or failure.

This systematic dataset is also may be helpful as a reference point for practitioners. In these cases, users may leverage the data to explore and uncover the key players in climate negotiations for advocacy purposes or strategic partnerships. This data can also be used in monitoring and evaluation endeavors through the tracking and analysis of shifts in the representation and leadership of various attending entities—especially as it relates to adjusting and tailoring specific strategies to future climate negotiations. Last but not least, advocates’ and practitioners’ use of our data for the identification of shortcomings in representation can inform organizations, governments, and related entities as to the dimensions of representation where they may be falling short, thereby helping to ensure that future COP attendance is more representative of all climate change stakeholders.

With increasing concerns over the slow pace of international climate negotiations and an ever-warming climate, it is important to identify and understand the strengths and weaknesses of the world’s current global climate cooperation forum. A natural place to start is in the consideration of the individuals who actually participate in this forum every year. The data described above allow for the systematic study of such individuals at a level of detail that was previously unavailable. We hope that this comprehensive data on individual attributes of climate negotiation participants for the past 32 years of climate change negotiations will pave the way for further research and dialogue on the importance of broad participation in climate change negotiations, ultimately fostering an understanding of how such participation may foster solutions to the challenge of global climate change.

Follow the Topic

-

Scientific Data

A peer-reviewed, open-access journal for descriptions of datasets, and research that advances the sharing and reuse of scientific data.

Related Collections

With Collections, you can get published faster and increase your visibility.

Data for crop management

Publishing Model: Open Access

Deadline: Apr 17, 2026

Data to support drug discovery

Publishing Model: Open Access

Deadline: Apr 22, 2026

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in