Behind the Paper: The Art of Losing - How Loss of Immunosuppressive Bacteria Shapes Immunotherapy Response

Published in Cancer and Microbiology

Beginning of a clinical trial

In November 2021, when the first patient was recruited into our study, we knew that we were at the beginning of a long journey. This journey would span over several years, building on encouraging results of our previous trial testing fecal microbiota transplantation1, and shaped by a sense of cautious optimism about what might lay ahead. What we were confident of, even then, was the idea the gut microbiome played a pivotal role in shaping the response to cancer immunotherapy.

Immunotherapy, using drugs known as immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICI), work by releasing the “brakes” present in our immune system, allowing antitumor T cells to mount a stronger response against cancer cells. These drugs have led to a significant increase in durable responses in several malignancies, including non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), melanoma and renal cell carcinoma (RCC). However, despite these advances, nearly half of patients exhibit primary resistance or eventually experience cancer recurrence, underscoring the need for combination strategies to improve clinical outcomes2.

Why the microbiome mattered

The gut microbiome—comprising of trillions of bacteria—has been identified as a promising candidate as both a biomarker and modulator of response to ICI. The microbiome has been profiled using shotgun metagenomics sequencing, on large cohorts of patients with various kind of cancers, across different countries, and consistent patterns have started to emerge. Patients who had certain bacteria, that the scientific community calls as “beneficial”, such as Akkermansia muciniphila or Bifidobacterium spp. seemed to respond very well to immunotherapy. On the contrary patients whose gut microbiome constituted mostly of a group of bacteria that is deemed as “detrimental” such as Enterocloster spp., Streptococcus spp., and Clostridium spp. seemed to consistently resist ICI response. Overuse of antibiotics, that are known to deplete the microbiome composition, was also associated with impaired immunotherapy efficacy, strengthening the belief that a “good microbiome composition” is critical to a beneficial immunotherapy response. Despite growing enthusiasm and a lot of effort however, the field is yet to distinctively define these “beneficial” bacteria and how they contribute to immunotherapy response3–7.

With these preliminary findings, many researchers including our lab, had been attempting to positively shift the microbiome composition in patients with cancer before they started their immunotherapy regime. Several groups had reported clinical success of fecal microbiota transplantation (FMT) in patients with refractory melanoma. In parallel, our group was also concluding our first phase I trial called MIMIC, which combined FMT from healthy individual donors with single agent ICI therapy in patients with previously untreatment advanced melanoma. We observed that FMT was not only safe, but improved the overall response rate nearly doubled in patients with NSCLC, with similarly improved response rate in melanoma1. These results provided compelling clinical proof-of-concept that the microbiome matters—but they left a critical question that we were eager to understand: how does FMT actually work, and could it work in other malignancies that were treated with immunotherapy, such as lung cancer?

Designing FMT-LUMINate – to go beyond efficacy and understand bacterial engraftment

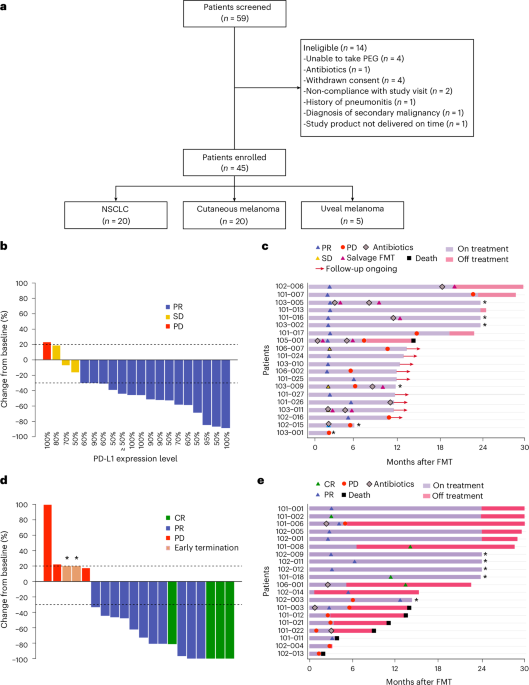

FMT-LUMINate was designed with an ambitious scope; to go beyond clinical efficacy and address this mechanistic gap. The trial consisted of 20 patients with advanced ICI treated with dual immunotherapy and 20 NSCLC patients with single agent immunotherapy, all of whom received FMT from individual healthy donors.

After 3 years of patient recruitment, longitudinal clinical follow up, and extensive downstream analyses of stool and blood samples collected before FMT and multiple timepoints after FMT, we began to systematically untangle the biological interplay between FMT, single or dual ICI and response. The most intuitive assumption that we all developed was that FMT allowed the introduction and engraftment of the “beneficial” bacteria from the donor into the patients’ microbiome, that would reshape the microbial ecosystem, and promote antitumor immunity.

Mining through the metagenomic data, we initially focused on strain-level analyses, building directly on results obtained from the MiMiC study and other earlier studies. We resolved down taxonomic changes to the strain resolution, using tools such as StrainPhlAn8, that helps us identify if a strain or subspecies of bacteria originated from the donor or the patients’ intrinsic microbiome. We tested whether strain engraftment from the donor would distinguish responders (R) from non-responders (NR). Instead, we found that strain-level engraftment was highly variable, with both R and NR showing efficient strain engraftment and hence engraftment of strains from the donor alone could not explain the response to FMT.

When engraftment failed to explain response, we shifted focus

As is often true in science, this apparent and disappointing dead-end became a turning point, prompting us to abandon a narrow focus and ask questions from a different perspective. Rather than focusing on what strains of bacteria the patients gained post FMT, we began to monitor how their microbiome composition changed relative to their baseline. We went back to square one and performed a simple counting exercise by binning all of the species that were present in the sample: whether they were found in the donor only, found in the patient only, and finally, what was present in the patient at baseline but no longer detected after FMT—in other words: what was lost. Through this exercise, we discovered that only the responders experienced pronounced and sustained loss or elimination of their baseline bacteria. They seemed to drastically lose intrinsic bacteria while gaining many new ones, not just from the donor alone, but from the surrounding environment as well. What also distinguished responders was not only how much was lost, but whatwas lost. Following FMT, responders consistently experienced elimination of a defined set of bacterial taxa—implicating the removal of specific, unfavorable microbes as a hallmark of response. Remarkably, we noticed that the responders seemed to consistently lose the same set of “detrimental bacteria” including Enterocloster spp., Streptococcus spp. and Clostridium spp., have all been previously linked to ICI resistance, and are pathognomonic of a dysbiotic gut9. This bacterial loss appeared to remodel the microbial niche, enabling the emergence of a eubiotic microbiome state. While conventionally microbiome studies largely rely on shotgun metagenomic sequencing, it does have its own set of limitations including a threshold of sequencing depth, below which, there can be a small percentage of true positive signals that don’t get picked up. To confirm that what we think are lost through sequencing data are truly lost and not just undetected, we performed complimentary techniques within our dataset, such as culturomics and targeted qPCR not limited by sequencing depth, and this pattern held true. Encouraged by what we found in our dataset, we wanted to see if other trials would show the same pattern or not. We utilized metagenomic data from MiMiC as well as publicly available datasets on other FMT in oncology trial conducted in different countries and clinical settings. Among all the different patterns we explored, the signature of depletion of deleterious baseline bacteria stood out to be the least variable and most biologically coherent.

From microbial loss to immune reprogramming

To establish a causal link, we turned to preclinical murine models. We humanized tumor bearing mice with stools samples from the responding after the loss of these deleterious bacteria. We then re-introduced the defined bacterial cocktail to half the mice, while the remaining received normal saline as control. Compared to control mice, where the tumor growth was controlled after single or dual ICI, mice receiving cocktail of bacteria resisted the ICI treatments. This confirmed the presence of these bacteria actively impairs therapeutic benefit. To understand how, we returned to the patients’ blood samples, and found that those who lost these bacteria from their baseline exhibited a far reduced immunosuppressive tryptophan metabolism and a favorable immune profile, characterized by increased effector CD8⁺ T cells and reduced regulatory T cells.

What this means for the future in the field of microbiome in oncology?

FMT-LUMINate demonstrated, that therapeutic success depends less on adding the “good” bacteria and more on removing the bad ones. While FMT itself provides a powerful proof-of-concept, the broader implication of our findings is even more exciting. If eliminating immunosuppressive microbial signals can restore effective anticancer immunity, then future strategies—potentially involving diet, lifestyle, or targeted microbiome modulation, or even utilizing bacteriophage-based approaches or other live biotherapeutic products to selectively remove these specific immunosuppressive bacteria—has the potential to make immunotherapy more effective for a larger number of patients10.

A final reflection: loss, collaboration, and team science

FMT-LUMINate could not have been possible with the effort of a single person, discipline, or institution. It was built through true team science and a collaboration between the CHUM and Lawson—spanning more than 5 countries, dozens of clinicians and scientists, wet labs and dry labs, bioinformaticians, nurses, research coordinators, regulatory teams, and trainees. It involved over 40 patients, hundreds of biological samples, and years of coordinated efforts across continents and time zones.

Team science is much like a puzzle. Each piece—solving a clinical problem or question, patient care, sample processing, sequencing, computational analysis—matters on its own, yet none is sufficient in isolation. Removing even one piece would make the picture incomplete. Only when every contributor is present and working together, does the full image emerge. In a way, this mirrors the biology we uncovered. Just as immunotherapy response was shaped not only by what was gained, but by what was selectively removed, scientific progress itself is often forged through refinement—by letting go of assumptions, narrowing focus, and allowing space for new understanding to take shape.

Above all, this work belongs to the patients. Their willingness to participate in early-phase clinical research—often with uncertain personal benefit—made this discovery possible. They are the most essential piece of this puzzle. Without them, there is no science, no insight, and no progress.

Sometimes, moving forward requires not adding more pieces—but understanding which ones need to be removed so the picture can finally come into focus.

References:

- Routy B, Lenehan JG, Miller WH, et al. Fecal microbiota transplantation plus anti-PD-1 immunotherapy in advanced melanoma: a phase I trial. Nat Med. 2023;29(8):2121-2132. doi:10.1038/s41591-023-02453-x

- Sharma P, Hu-Lieskovan S, Wargo JA, Ribas A. Primary, Adaptive, and Acquired Resistance to Cancer Immunotherapy. Cell. 2017;168(4):707-723. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2017.01.017

- Routy B, Le Chatelier E, Derosa L, et al. Gut microbiome influences efficacy of PD-1–based immunotherapy against epithelial tumors. Science. 2018;359(6371):91-97. doi:10.1126/science.aan3706

- Duttagupta S, Hakozaki T, Routy B, Messaoudene M. The Gut Microbiome from a Biomarker to a Novel Therapeutic Strategy for Immunotherapy Response in Patients with Lung Cancer. Curr Oncol. 2023;30(11):9406-9427. doi:10.3390/curroncol30110681

- Matson V, Fessler J, Bao R, et al. The commensal microbiome is associated with anti–PD-1 efficacy in metastatic melanoma patients. Science. 2018;359(6371):104-108. doi:10.1126/science.aao3290

- Elkrief A, Méndez-Salazar EO, Maillou J, et al. Antibiotics are associated with worse outcomes in lung cancer patients treated with chemotherapy and immunotherapy. Npj Precis Oncol. 2024;8(1):143. doi:10.1038/s41698-024-00630-w

- Thomas AM, Fidelle M, Routy B, et al. Gut OncoMicrobiome Signatures (GOMS) as next-generation biomarkers for cancer immunotherapy. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2023;20(9):583-603. doi:10.1038/s41571-023-00785-8

- Blanco-Míguez A, Beghini F, Cumbo F, et al. Extending and improving metagenomic taxonomic profiling with uncharacterized species using MetaPhlAn 4. Nat Biotechnol. 2023;41(11):1633-1644. doi:10.1038/s41587-023-01688-w

- Yonekura S, Terrisse S, Alves Costa Silva C, et al. Cancer Induces a Stress Ileopathy Depending on β-Adrenergic Receptors and Promoting Dysbiosis that Contributes to Carcinogenesis. Cancer Discov. 2022;12(4):1128-1151. doi:10.1158/2159-8290.CD-21-0999

- Elkrief A, Pidgeon R, Maleki Vareki S, Messaoudene M, Castagner B, Routy B. The gut microbiome as a target in cancer immunotherapy: opportunities and challenges for drug development. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2025;24(9):685-704. doi:10.1038/s41573-025-01211-7

Follow the Topic

-

Nature Medicine

This journal encompasses original research ranging from new concepts in human biology and disease pathogenesis to new therapeutic modalities and drug development, to all phases of clinical work, as well as innovative technologies aimed at improving human health.

Related Collections

With Collections, you can get published faster and increase your visibility.

Stem cell-derived therapies

Publishing Model: Hybrid

Deadline: Mar 26, 2026

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in