Between Rainfall and Resilience: Understanding Drought Trends in the Niger River Basin

Published in Earth & Environment and Plant Science

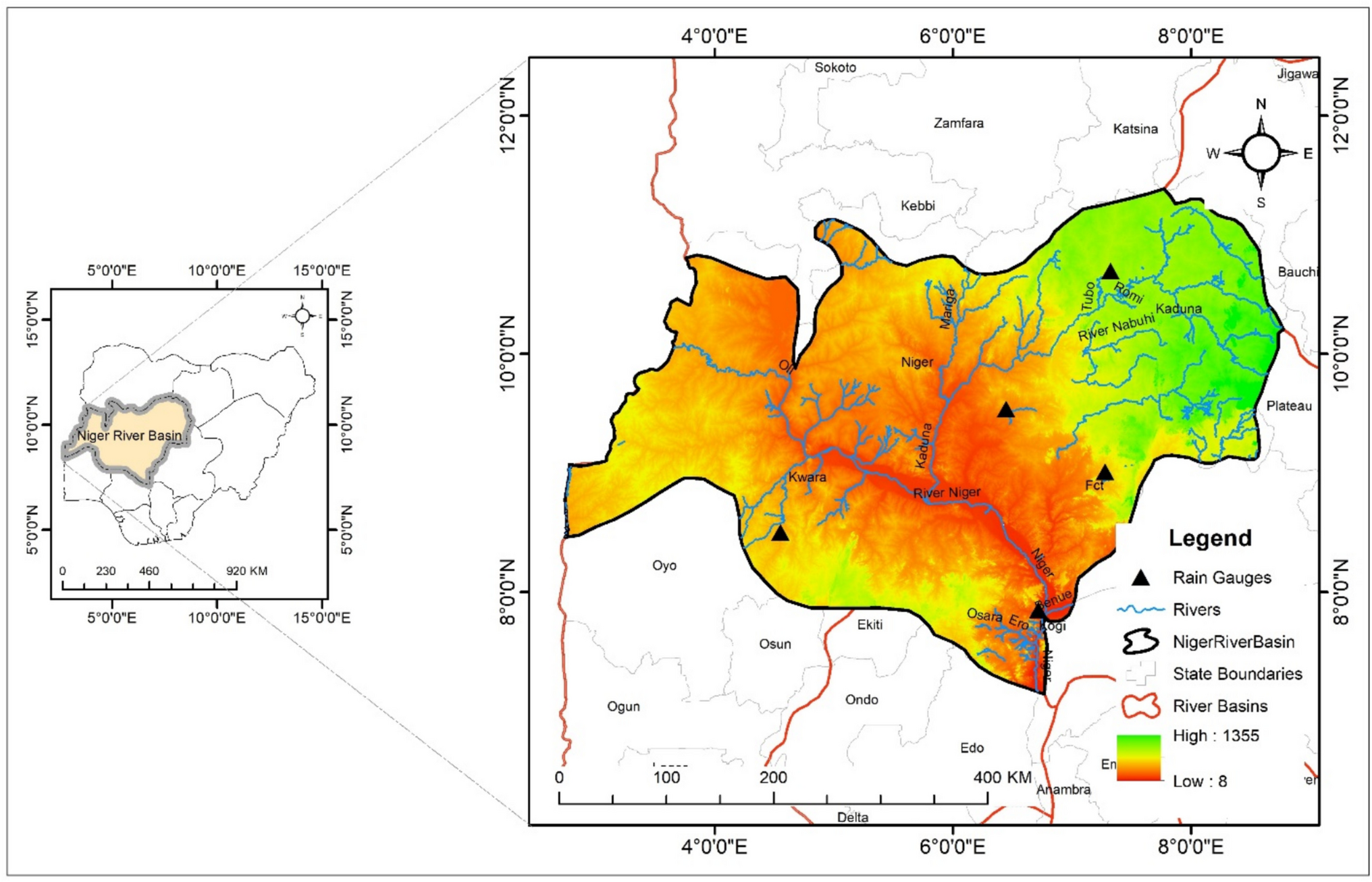

This study is part of my ongoing PhD research at the Centre for Dryland Agriculture, Bayero University, Kano, under the supervision of Professor Salisu Mohammed. The broader thesis explores how climate variability and long-term habitat fragmentation are shaping habitat quality in the Niger River Basin (NRB), Nigeria. At its core, the research seeks to understand how ecological systems are responding to environmental changes, especially those driven by shifts in climate and human land use.

The Niger River Basin is not just a geographical entity—it is an ecological lifeline. It supports millions of people and harbors diverse wildlife. It is home to internationally recognized conservation areas, such as the Borgu and Lake Kainji National Parks, and two Ramsar-designated wetlands of international importance: the Lake Kainji Wetland and the Lower Kaduna–Middle Niger Wetland. These landscapes host exotic and endangered species, sustain local agriculture, and regulate regional hydrology. However, despite their importance, these ecosystems face growing stress from climatic extremes, particularly the increasing frequency and intensity of droughts.

The motivation for this paper stemmed from a simple but pressing question: Is the Niger River Basin becoming drier or wetter, and what does that mean for the ecosystems and people who depend on it?

In many parts of sub-Saharan Africa, rainfall variability dictates the rhythm of life. Agriculture is largely rain-fed, water supply systems are seasonal, and natural habitats are tied to hydrological cycles. Yet, recent decades have brought a series of disruptive droughts, some of which have led to devastating crop failures, livestock losses, and ecological degradation. While these droughts are experienced locally, their causes and patterns are often regional or even global. I wanted to investigate these changes not just anecdotally, but scientifically, looking for trends, signals, and shifts across both space and time.

This study focuses specifically on meteorological drought and long-term rainfall trends in the Nigerian portion of the NRB. To approach this, I used a suite of statistical techniques, blending both classical and modern approaches to trend detection and drought analysis.

The rainfall data was subjected to advanced statistical tools, including the Bayesian Estimator of Abrupt Change, Seasonality, and Trend (BEAST), which can detect sudden shifts or regime changes in time series data. In addition, I applied the Mann–Kendall (MK) and its modified versions (MMK, SMK), which are standard tools for assessing monotonic trends. To offer a fresh perspective, I also employed the Innovative Trend Analysis (ITA) method, which does not rely on assumptions of normality or homogeneity and allows for clearer visual interpretation of rainfall changes.

The findings were both surprising and insightful.

To begin, while the BEAST analysis found that abrupt changes in rainfall were not significant in the majority of the basin, all trend detection methods (MK, MMK, SMK, and ITA) agreed on one thing: annual rainfall is increasing across much of the basin. This contradicts prevalent narratives that the region is experiencing prolonged drying, pointing to a more complex reality of more fluctuation but potentially enhanced water availability in the long run.

However, when rainfall was broken down seasonally, the story changed. The MAM season (March–May), which is critical for early planting and the beginning of the agricultural season, showed a significant decrease in rainfall. In contrast, the SON season (September–November) recorded increasing trends, which could shift the agricultural calendar and complicate water management for farmers and policy planners alike.

To assess variability, I calculated the coefficient of variation (CV) and the precipitation concentration index (PCI). The PCI results indicated that rainfall distribution varied from low to high concentration across stations, which is a red flag for flood-drought extremes. Highly concentrated rainfall in a few months increases the risk of floods, while longer dry spells stress both crops and ecosystems.

The Standardized Precipitation Index (SPI), used to quantify meteorological drought, revealed that severe drought events were most pronounced in the 1970s and 1980s, aligning with well-documented Sahelian droughts. These historical droughts left lasting impacts on land cover, water availability, and even migration patterns in the NRB.

The implications of this study are far-reaching. An increase in annual rainfall may sound promising, especially for rain-fed agriculture and groundwater recharge. But the seasonal shifts and concentration patterns signal challenges for ecological balance and food security. Habitat quality, particularly in wetland and savanna ecosystems, depends not just on how much rain falls, but when and how evenly it falls.

This research lays the foundation for further investigation into how these hydrological trends interact with land use and habitat fragmentation, key elements of my doctoral thesis. Ultimately, by understanding how climate variability affects the Niger River Basin, we can better plan for resilient landscapes, sustainable livelihoods, and effective conservation strategies.

Follow the Topic

-

Environmental Science and Pollution Research

This journal serves the international community in all broad areas of environmental science and related subjects with emphasis on chemical compounds.

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in