Biodiversity conservation

Published in Sustainability

Poster: A sacred grove in the Western Ghats, India

In 1993, there were publications related to traditional ecological knowledge in human ecology, cultural anthropology and ethnobiology. But no literature existed on biodiversity conservation and indigenous peoples with a global perspective. We sought to address that gap with a short paper in Ambio on biodiversity. At the time we had no idea that indigenous knowledge for biodiversity conservation would become a major topic in international biodiversity conservation.

Madhav Gadgil

Panchavati, Pune, Maharashtra State, India

Behind the Paper: Indigenous knowledge: From local to global

Indigenous knowledge for biodiversity conservation is as relevant today as it was in the early 1990s, except that its significance has been recognized by a larger group of scholars, practitioners and even policy-makers. Today the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES) has a Task Force on Indigenous and Local Knowledge Systems. The wider recognition of indigenous knowledge is a positive development in today’s difficult world. Indigenous peoples themselves well understood its importance all along.

My love affair with sacred groves, India’s treasure troves of biodiversity, began in August 1971 a month after I returned from Harvard with a Ph.D. in Biology. As I drove along the hills of the northern Western Ghats, I felt increasingly depressed at the sight of the barren hills covered with tropical rain forest until the early 1960s. Suddenly I saw a five-hectare patch of luxuriant evergreen forest, within which towered four trees of Canarium strictum, a species characteristic of the southern Western Ghats, 500 kilometers away.

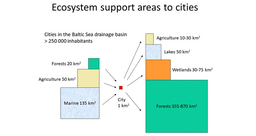

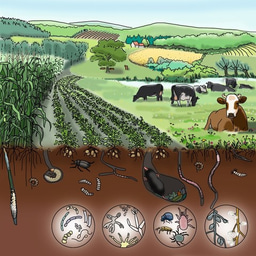

The reigning hypothesis among conservationists at the time was that such sacred groves represented lingering elements of nature worship prevalent in primitive societies; they had no secular functions but persisted because of religious belief. Our field surveys and interviews revealed that people perceived and valued what we now call the “ecosystem services” that the sacred groves offered and were continuing to protect them because they wished to avail themselves of these benefits. Most groves protected water sources; many sheltered valuable medicinal plants, while larger ones served as refugia for animals hunted outside the sacred groves.

Six months later, I received a letter from people of Gani, a village in the Western Ghats, who were shocked by the Forest Department marking trees in their sacred grove for felling. All the surrounding region had been completely deforested, and people had no source of dead-wood or of leaf litter for preparing the paddy fields except for the grove. Moreover, apart from a village well, the only perennial water source for the cattle or for the people working in the field was a spring in the grove. I met the Head of Forestry in the state, who stated that such groves were nothing but worthless “stands of overmatured timber”. This vividly brought home to me how people at the grass-roots valued ecosystem services and how the bureaucracy trashed such services. Evidently, if we wish to nurse our planet back to a healthier state and continue to preserve its heritage of biodiversity, we must begin to respect the ecosystem people on our planet and draw upon their knowledge.

However, urban communities with no links to people at grass-roots are under a misconception that only state efforts can save the natural resources, and this misconception informs programmes of organizations such as Worldwide Fund for Nature (WWF) as well. Today, it is truly inspiring to observe the widespread recognition and appreciation - in science, management, and international conventions - of the role of ecosystem people in stewardship of biodiversity, ecosystem services, and nature's contribution to people. But recognition is not enough: still much needs to be done to implement such ideas. Support for indigenous stewardship of biodiversity is urgently needed since it provides the foundation for livelihoods and wellbeing for the still growing human population confronted with climate change, biodiversity loss, and other environmental challenges.

Madhav Gadgil

E-mail: madhav.gadgil@gmail.com

Original article

Gadgil, M., F. Berkes, and C. Folke. 1993. Indigenous knowledge for biodiversity conservation. Ambio 22(2-3): 151-156.

All articles in Ambio's 50th Anniversary Collection: Biodiversity Conservation

Editorial

McNeely, J. 2021. How to conserve biological diversity: Perspectives from Ambio. 50th Anniversary Collection: Biodiversity Conservation. Ambio. Volume 50.

Behind the paper

Bengtsson, J., P. Angelstam, T. Elmqvist, U. Emanuelsson, C. Folke, M. Ihse, F. Moberg, and M. Nyström. 2021. Reserves, resilience and dynamic landscapes 20 years later. 50th Anniversary Collection: Biodiversity conservation. Ambio Volume 50.

Gadgil, M., F. Berkes, and C. Folke. 2021. Indigenous knowledge: From local to global. 50th Anniversary Collection: Biodiversity conservation. Ambio Volume 50.

Perspective

Pimm, S. 2021. What is biodiversity conservation? 50th Anniversary Collection: Biodiversity conservation. Ambio Volume 50.

Sayer, J., C. Margules, and J. McNeely. 2021. People and biodiversity in the 21st century. 50th Anniversary Collection: Biodiversity conservation. Ambio Volume 50.

Follow the Topic

What are SDG Topics?

An introduction to Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) Topics and their role in highlighting sustainable development research.

Continue reading announcement

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in