Biopsychosocial models of stress-sensitive epilepsy needed to advance translation

Published in Neuroscience

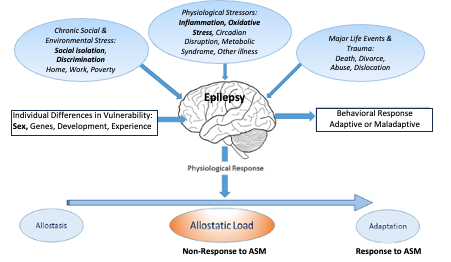

Resistance to antiseizure medications (ASM) is a major problem in the management of epilepsy, has wide impact on morbidity and mortality and, if solved, could result in profound improvements in quality-of-life, employment participation and social functioning 1, for both individuals affected and their families, as well as the avoidance of Disability Adjusted Life Years (DALYs) and years of life lost averted2. ASM resistance, which can quadruple health care costs of condition management, has been a refractory problem and inflammatory and oxidative stress mechanisms are increasingly being explored3,4. Recent evidence suggests sex differences in the prognosis for ASM resistance in idiopathic generalised epilepsy, mediated by response to environmental stress5. Stress-sensitivity, which differs between sexes, may be related to early life adversity in children and adults with epilepsy and occurs in >60% of patients6. A biopsychosocial model (adapted from7) linking stress with behaviour is shown in the figure below.

In a recent issue of Nature Neuroscience, Kumar and colleagues provide cellular evidence of brain microglial activation and peripheral T-cell and monocyte recruitment in surgical specimens resected for intractable focal epilepsy8. The authors make the comparison with the gene expression profiles of microglia seen in the nervous system of people with multiple sclerosis. Interestingly, neuroinflammation is also a key factor interacting with dysregulation of the HPA-axis and adult neurogenesis in the mechanisms underlying depression9. Furthermore, there is compelling evidence that crosstalk between peripheral inflammatory mechanisms and brain microglia link environmental stress to the development of depression10. Hence there seems to be a convergence of ideas in several episodic neuropsychiatric conditions around the pathogenetic roles of environmental stress with peripheral/neural inflammatory crosstalk.

There is certainly cause for optimism in solving ASM resistance, but we believe there is a gap in upstream, more biopsychosocial studies linking environmental stress with epilepsy outcomes and here we wish to highlight an agenda to drive advances in the field. First, more longitudinal data are needed to link stressful life events to ASM resistance via stress-sensitivity, to generate biopsychosocial signatures of susceptibility and to explore sex differences, as well as better quantity long-term socio-economic impacts. Second, in vivo research on inflammatory mechanisms mediating the response to environmental stress and resulting in the alteration of brain networks in people with epilepsy; animal studies may additionally show optimal time windows for reversibility. Third, innovative and personalised ideas for stress management are needed, to maximise quality of life, independence and social functioning and minimise avoidable adverse health events and their costs, taking account of the holistic lived experience of people with epilepsy. At the moment, this area of interdisciplinary research is not well represented or funded but could have significant impact for the many people living with epilepsy whose seizures are triggered by stress.

References

- Christensen J, Dreier JW, Sun Y, et al. Estimates of epilepsy prevalence, psychiatric co-morbidity and cost. Seizure 2023; 107: 162-71.

- Collaborators GBDE. Global, regional, and national burden of epilepsy, 1990-2016: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Lancet Neurol 2019; 18(4): 357-75.

- Loscher W, Potschka H, Sisodiya SM, Vezzani A. Drug Resistance in Epilepsy: Clinical Impact, Potential Mechanisms, and New Innovative Treatment Options. Pharmacol Rev 2020; 72(3): 606-38.

- Zhang S, Chen F, Zhai F, Liang S. Role of HMGB1/TLR4 and IL-1beta/IL-1R1 Signaling Pathways in Epilepsy.Front Neurol 2022; 13: 904225.

- Shakeshaft A, Panjwani N, Collingwood A, et al. Sex-specific disease modifiers in juvenile myoclonic epilepsy. Sci Rep 2022; 12(1): 2785.

- van Campen JS, Jansen FE, Steinbusch LC, Joels M, Braun KP. Stress sensitivity of childhood epilepsy is related to experienced negative life events. Epilepsia 2012; 53(9): 1554-62.

- McEwen BS, Akil H. Revisiting the Stress Concept: Implications for Affective Disorders. J Neurosci 2020; 40(1): 12-21.

- Kumar P, Lim A, Hazirah SN, et al. Single-cell transcriptomics and surface epitope detection in human brain epileptic lesions identifies pro-inflammatory signaling. Nat Neurosci 2022; 25(7): 956-66.

- Troubat R, Barone P, Leman S, et al. Neuroinflammation and depression: A review. Eur J Neurosci 2021; 53(1): 151-71.

- Nettis MA, Pariante CM. Is there neuroinflammation in depression? Understanding the link between the brain and the peripheral immune system in depression. Int Rev Neurobiol 2020; 152: 23-40.

Fam Vivian Bekkengen

Lived experience

Norway

Professor David McDaid

Care Policy and Evaluation Centre

London School of Economics and Political Science, UK

d.mcdaid@lse.ac.uk

Prof Marie-Pierre Moisan

INRAE Nutrineuro

Bordeaux, France

marie-pierre.moisan@inrae.fr

Professor Deb K Pal

MRC Centre for Neurodevelopmental Disorders

King’s College London, UK

deb.pal@kcl.ac.uk

Dr Kaja Selmer

Oslo University Hospital

Oslo, Norway

k.k.selmer@umedisin.no

Dr Marte Syvertsen

Vestre Viken Neuroscience

Drammen, Norway

marsyv@vestreviken.no

Follow the Topic

-

Nature Neuroscience

A multidisciplinary journal that publishes papers of the highest quality and significance in all areas of neuroscience, with contributions in molecular, cellular, systems and cognitive neuroscience, psychophysics, computational modeling and diseases of the nervous system.

Your space to connect: The Psychedelics Hub

A new Communities’ space to connect, collaborate, and explore research on Psychotherapy, Clinical Psychology, and Neuroscience!

Continue reading announcement

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in