Boosting climate motivation with psychological interventions

Published in Behavioural Sciences & Psychology

Climate change is one of the biggest challenges facing humanity. Around the world, people, wildlife and societies are already experiencing devastating effects. To address this, billions of people will need to choose actions that benefit the environment. However, these actions often require physical effort, for example cycling rather than driving or cleaning waste for recycling. We know from previous research that humans generally avoid effortful actions1, especially when they don’t benefit us personally2. This could be a key barrier to choosing pro-environmental actions and it is essential to identify how we can boost motivation to help the environment.

One promising approach is using interventions based on psychological research. These often consider why people might not be motivated to reduce climate change, for example because the consequences are psychologically distant: uncertain, far in the future, affecting distant places and people3. An intervention to reduce psychological distance therefore uses text and images to show that climate change is already impacting the individual and their local community.

While interventions like this improve attitudes or intentions to take pro-environmental actions, my colleagues and I noticed a few issues with this previous work. First, research that asks people what they intend to do in future cannot know that they really will actually put in effort at the time. Second, the few studies that do measure motivation to exert effort for the environment lack a control condition to test whether findings are specific to climate motivation.

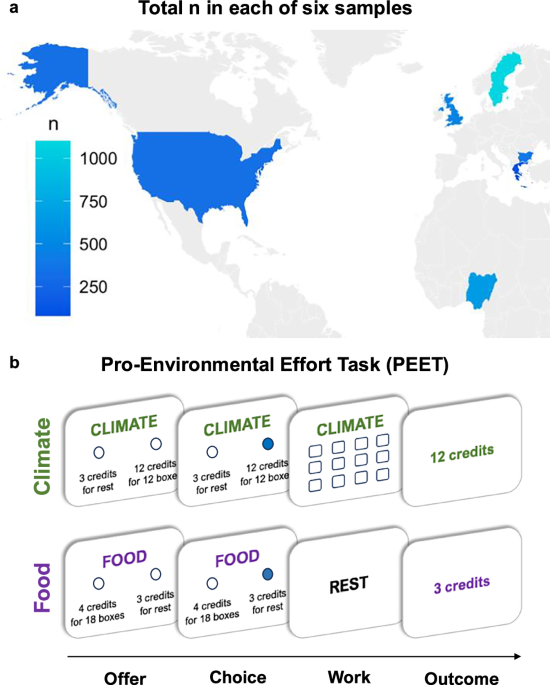

To overcome these and other issues, we designed the Pro-Environmental Effort Task (PEET). On each of 24 rounds of the task, participants can choose to ‘rest’ – not exert any effort – and obtain 3 credits, or ‘work’ – exert effort by clicking lots of boxes – to obtain a higher number of credits (4, 12 or 20). On half of the trials, credits were translated into donations to a charity that “prevents climate change by reducing carbon emissions”. On the other half, donations were for a control charity that “prevents starvation by providing food”. Importantly, if participants choose to work, they must immediately exert the effort. The level of effort required varied on different rounds and the number of boxes participants have to click is tailored to their maximum ability.

We had the opportunity to gather a large international sample of participants via the International Climate Psychology Collaboration led by Professor Madalina Vlasceanu, Dr Kimberly Doell, and Professor Jay Van Bavel. This collaboration crowdsourced 11 psychological interventions to increase climate change mitigation from experts in the field and coordinated data collection from 59,508 participants in 63 countries4. The full dataset is freely available online5.

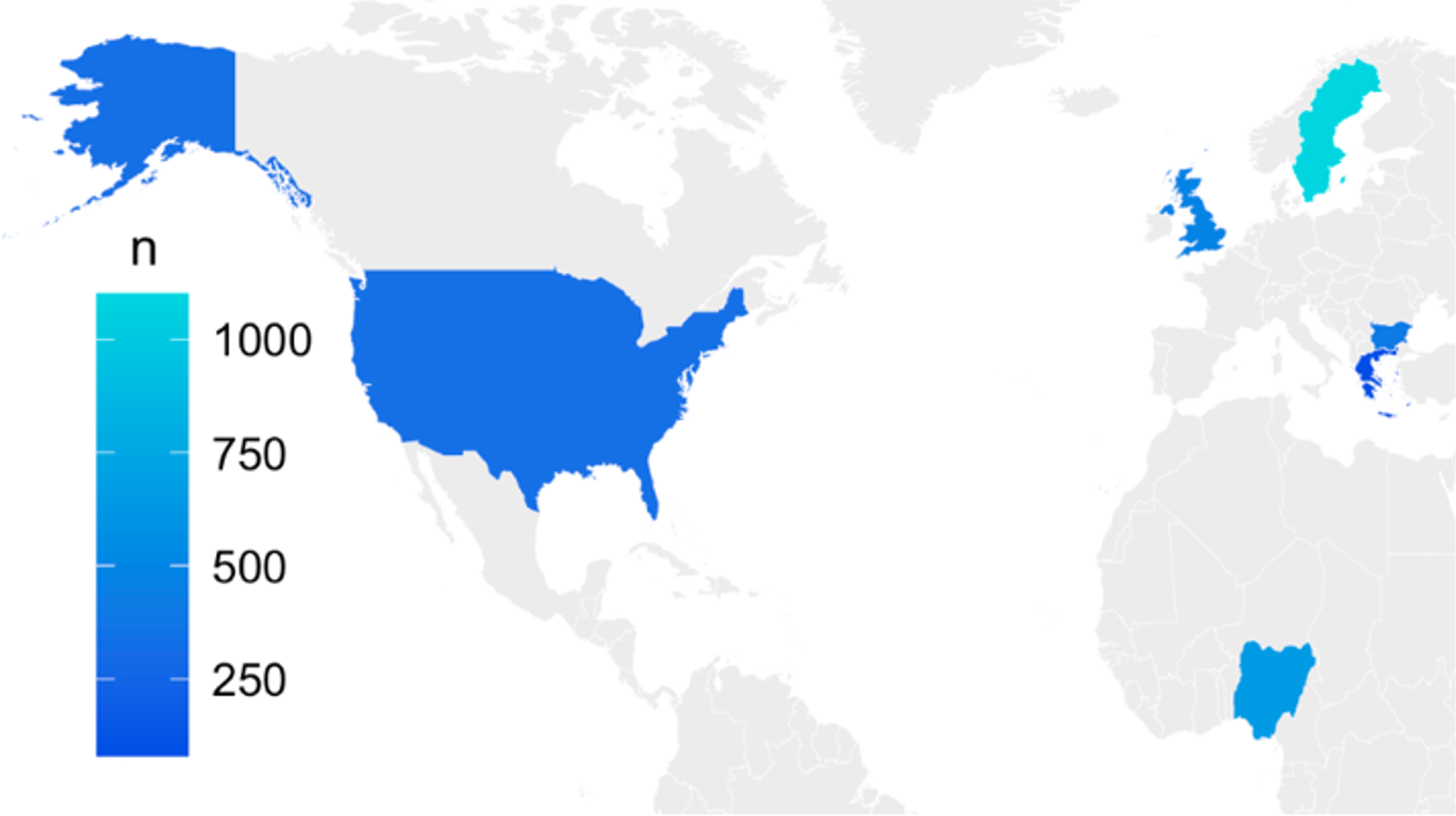

For the Pro-Environmental Effort Task, we teamed up with colleagues from the collaboration to collect data in the UK, USA, Bulgaria, Greece, Sweden, and Nigeria. Members of the team translated the task materials into the relevant languages and adapted the content of the interventions to each country. The 3,055 participants from these 6 countries were randomly assigned to experience one of the 11 interventions or a control group who read a passage of text unrelated to climate change. They then completed a range of measures, including the Pro-Environmental Effort Task and questions about their beliefs and attitudes towards climate change. Our findings are published today in Communications Psychology6.

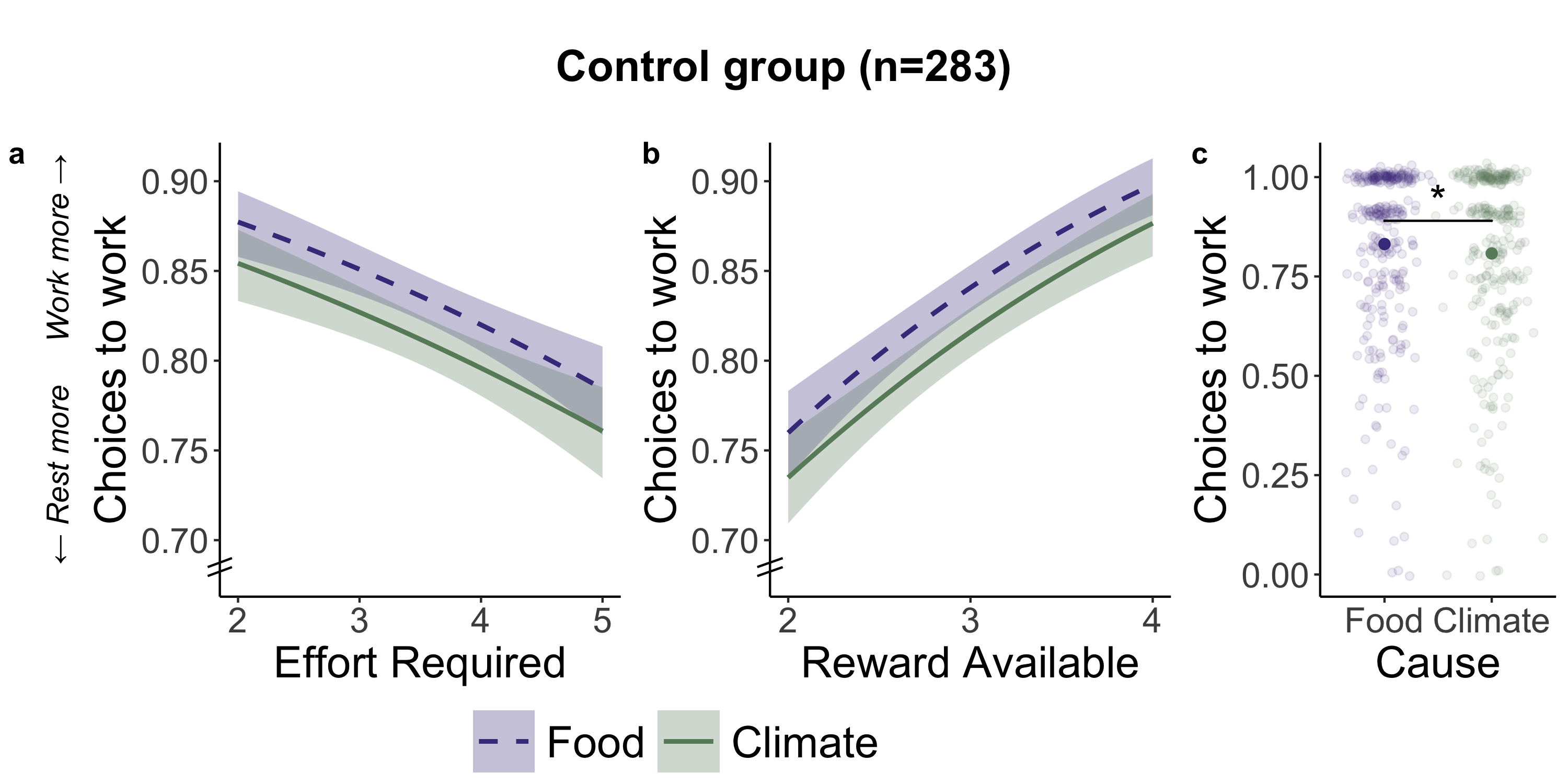

Our first set of analyses looked at how people make choices between resting or working to benefit the climate and the control charity that provides food. As we expected, people were more willing to work when the reward (the number of credits) was higher and when the effort required (number of boxes to click) was lower. This supports our original idea that effort can act as a barrier to pro-environmental action. We also used advanced analysis methods to fit mathematical algorithms to the participants’ choices. These capture how people devalue rewards by the effort required to obtain them and precisely quantify motivation for each individual.

Next, we compared motivation to help between the two charities in the control group that did not experience an intervention. Overall, these participants were more willing to exert effort to provide food than to reduce climate change. This finding matches data that real-world donations are lower to climate charities than international aid organisations and further emphasises the importance of identifying effective interventions. Fortunately, when we looked at the effect of the interventions, there was evidence that some of them did boost pro-environmental motivation, relative to the control cause.

Fig. 3 Effort, reward, and cause determine choices to exert effort for the climate and food charities | a Participants in the control group, who did not experience a pro-environmental intervention, chose to exert physical effort for rewards more when the level of effort required was lower. b Choices to work were also higher when the reward available was larger. c Control participants were more willing to choose work to help the food charity compared to the climate charity.

Two of the interventions robustly increased relative motivation to help prevent climate change, across lots of different analyses to control for other potential explanations. The first was the intervention based on psychological distance that showed participants climate change is happening now and affecting them and their communities. The second demonstrated how climate change threatens participants’ way of life and framed acting as the patriotic thing to do, based on a psychological theory called system justification. Finally, we looked at differences between people in how willing they were to exert effort for the environment. We found this was related to their belief that climate change is a real, man-made issue and their support for policies that protect the environment, as well as their overall motivation.

Overall, our work establishes a new measure of motivation to exert effort to help the environment, which can be administered online quickly and easily to participants around the world. Throughout our analyses, we demonstrated the advantages of the Pro-Environmental Effort Task and how it overcomes the previous issues that prompted the project. Using this task, we found people were less willing to work for the environment when it required a lot of effort and that without an intervention, participants had lower pro-environmental motivation compared to a control cause. However, interventions that reduce the perceived distance to climate impacts or show how climate action is patriotic and protects participants’ way of life overcome this. We hope these results contribute to a growing effort to use behavioural science to help limit the devastating impacts of climate change7,8.

References:

-

Chong, T. T.-J. et al. Neurocomputational mechanisms underlying subjective valuation of effort costs. PLoS Biol. 15, e1002598 (2017).

-

Lockwood, P. L. et al. Prosocial apathy for helping others when effort is required. Nat. Hum. Behav. 1, 1–10 (2017).

-

Jones, C., Hine, D. W. & Marks, A. D. G. The future is now: reducing psychological distance to increase public engagement with climate change. Risk Anal. 37, 331–341 (2017).

-

Vlasceanu, M. et al. Addressing climate change with behavioral science: a global intervention tournament in 63 countries. Sci. Adv. 10, eadj5778 (2024).

-

Doell, K.C. et al. The International Climate Psychology Collaboration: Climate change-related data collected from 63 countries. Sci. Data 11, 1066 (2024).

-

Cutler, J. et al. Psychological interventions that decrease psychological distance or challenge system justification increase motivation to exert effort to mitigate climate change. Commun. Psychol. (2025).

-

Lamm, C. et al. Leveraging the Social Neuroscience of Prosocial Behavior to Advance Our Understanding of Pro-environmental Behavior. Environmental Neuroscience. Springer, Cham. (2024).

- Todorova, B. et al. Neuroscience and climate action: intersecting pathways for brain and planetary health. Curr. Opin. Behav. Sci. 63, 101522 (2025).

Follow the Topic

-

Communications Psychology

An open-access journal from Nature Portfolio publishing high-quality research, reviews and commentary. The scope of the journal includes all of the psychological sciences.

Ask the Editor – Collective decision-making

Got a question for the editor about Experimental Psychology and Social Psychology? Ask it here!

Continue reading announcementRelated Collections

With Collections, you can get published faster and increase your visibility.

Intensive Longitudinal Designs in Psychology

Publishing Model: Open Access

Deadline: Mar 31, 2026

Replication and generalization

Publishing Model: Open Access

Deadline: Dec 31, 2026

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in