Building Nanomaterials by Guiding Tiny Particles to Link Together

Published in Chemistry, Materials, and Mechanical Engineering

Explore the Research

Page not found | Nature

Page not found

Nanomaterials—materials built from nanometer-sized pieces—have captured the attention of scientists because of the unusual ways they interact with light, electricity, and react chemically. These properties do not just depend on what the material is made of, but also on how its tiny building blocks are arranged. Changing the arrangement of nanoparticles can alter how electrons flow, how photons scatter, or how strong the material is.

One way nanoparticles assemble is through a process called oriented attachment (OA), where individual particles align in the same or a twin-related orientation and fuse so that their atomic structures either match or form twins. This produces larger crystals that behave almost as if they were grown atom by atom, even though they are actually made from smaller pieces. What has puzzled scientists for years is that OA doesn’t happen randomly—particles often “choose” to attach on specific crystal surfaces, or facets, over and over again. Why would particles consistently prefer one surface over another when, in principle, any aligned surface would reduce energy?

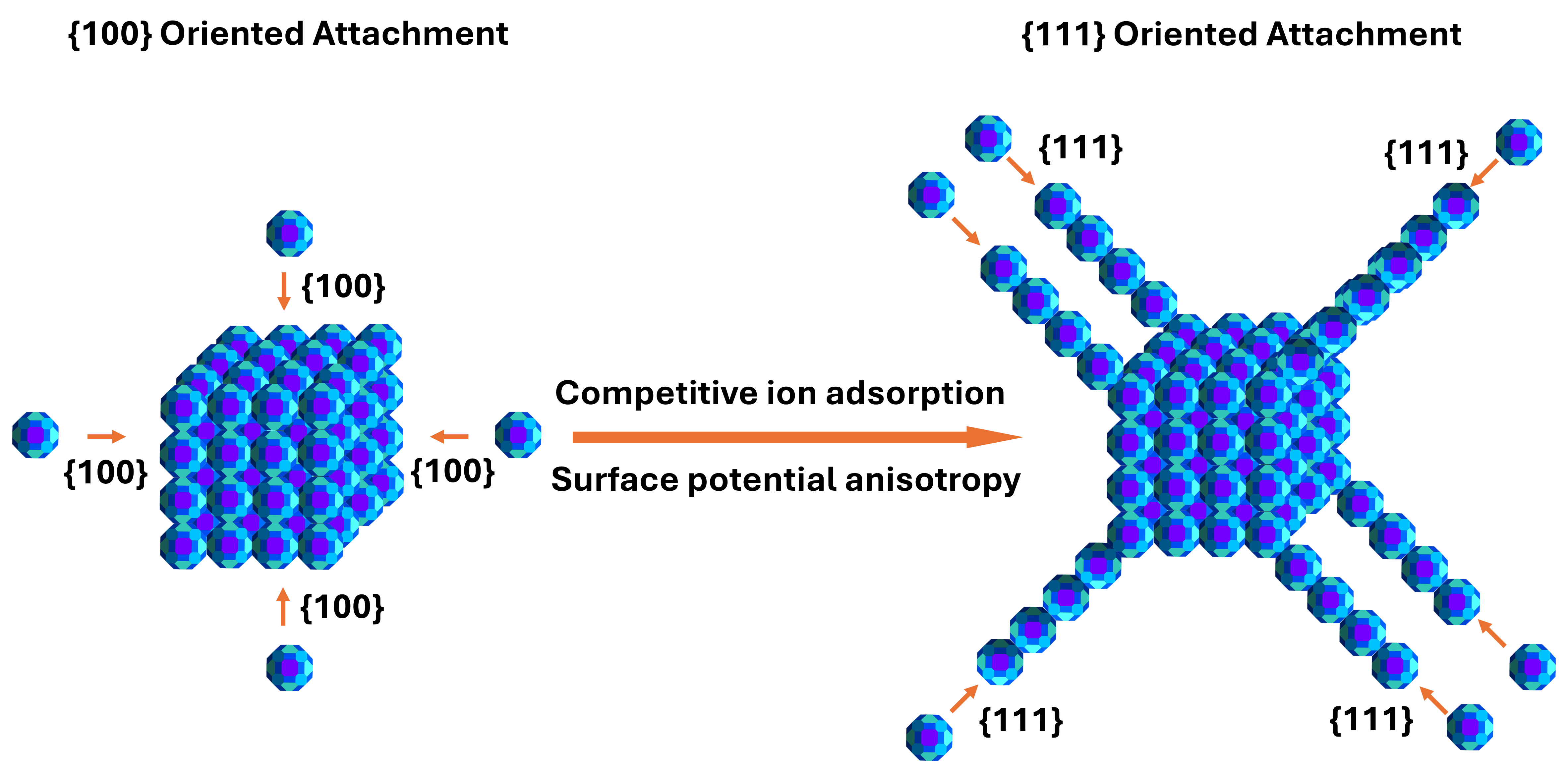

In our recent work, we solved this mystery. We found that the chemical environment around nanoparticles can create uneven surface charges on different facets of the same particle. This unevenness produces tiny electrostatic torques—rotational forces—that physically twist particles into the correct orientation for facet-specific attachment. By controlling which ions are present in the solution where nanoparticles float, we were able to guide them first to attach on one facet and then later to switch and attach on another. Using this mechanism, we created beautiful branched platinum (Pt) “nanocubes,” structures that start as compact cubes and then sprout diagonal arms.

From Cubes to Branches

We mixed a platinum salt (K₂PtCl₄) with formic acid in water at room temperature. Within about ten minutes, tiny platinum nanoparticles—each only ~3 nanometers across—formed. Over the next hour, the nanoparticles first assembled into cube-like structures tens of nanometers in size, and then those cubes began to sprout rod-like branches.

We used high-resolution imaging techniques like transmission electron microscopy (TEM) and cryogenic TEM. Early in the reaction, we saw loose clusters of nanoparticles jostling around, separated by thin layers of liquid. Over time, the particles reorganized and lined up, snapping together face-to-face. Initially, they did so mainly on their {100} facets—a notation for flat, square surfaces of a cubic crystal. This stage created solid cubic cores.

But after about 45 minutes, the behavior changed. The particles began attaching instead on the {111} facets—so that branches grew diagonally out of the cube. This two-stage process produced intricate branched mesocrystals: structures that look like single crystals but are actually made from many nanoparticles fused in precise orientation.

Why Did the Facet Preference Change?

The switch from {100} to {111} attachment could not be explained simply by energy minimization. Both types of attachment reduce surface energy, so why would the system change its preference mid-way through growth?

We suspected surface charge played a role. When nanoparticles sit in a solution, ions from the liquid stick to their surfaces. Different facets can attract different ions, leading to variations in their surface potential (a measure of how positive or negative the surface is). As nanoparticles fuse together and the total surface area shrinks, the balance of ions on the surfaces also shifts.

To probe surface charging, we measured the zeta potential, an experimental indicator of surface potential, for particles with {100}- and {111}-dominated surfaces under different conditions. At early times, the {100} surface was less negative than the {111} surface, favoring {100}-{100} attachment. As the reaction proceeded and the total nanoparticle surface area decreased, the {100} surface became more negative than the {111} surface. This inversion flipped the preferred attachment direction to {111}.

The key insight is that it’s not just the magnitude of repulsion that matters. Because different facets have different surface potentials, the mismatch between them creates a torque. Picture two magnets twisting into alignment: the uneven electrostatic fields act like a steering force, orienting the nanoparticles before they touch.

The Role of Competing Ions

But what caused the change in surface potentials in the first place? The answer lies in competitive ion adsorption. During the reaction, several ions are present: hydrogen (H⁺), potassium (K⁺), chloride (Cl⁻), and formate (HCOO⁻). These ions compete for spots on the nanoparticle surfaces, and different facets have different preferences.

Experiments showed that H⁺ ions tend to bind more strongly to the {100} facets, keeping them relatively neutral early on. Over time, as the total surface area of Pt nanoparticles shrinks, chloride and formate ions crowd in. On the {100} facets, this overwhelms the stabilizing effect of H⁺, driving the surface potential strongly negative. The {111} facets, by contrast, lose some H⁺ and Cl⁻ while gaining formate, shifting their potential only slightly. This imbalance flips the relative surface charges of the two facets and, in turn, the direction of OA.

We confirmed this picture using advanced surface analysis (TOF-SIMS) and theoretical calculations (density functional theory). Both supported the idea that dynamic competition between chloride and formate ions on different surfaces drives the observed switch.

Why This Matters

Understanding and controlling OA is more than just an academic puzzle. It opens a pathway to design nanomaterials with tailored shapes and properties. Unlike conventional crystal growth, which adds atoms one by one, OA lets nanoparticles self-organize into complex architectures. By tuning the ionic environment, we can dictate not only how particles stick together but also when and where they switch to new attachment modes.

This strategy is powerful because it is generalizable. Almost all crystalline materials expose different facets, and almost all surfaces interact differently with ions or with changes in pH. That means this principle could be applied to metals, oxides, semiconductors, and beyond. For example, electrostatic torques driven by ion competition could help guide the assembly of photocatalysts with improved efficiency, battery materials with better charge transport, or plasmonic structures that manipulate light in new ways.

Perhaps most intriguingly, the mechanism is externally tunable. Unlike forces that come from the intrinsic symmetry of a material (such as van der Waals or dipole interactions), electrostatic interactions can be adjusted on demand by changing the solution chemistry. That means researchers can design dynamic assembly processes that evolve over time, producing multi-stage structures like our branched platinum cubes.

Conclusion

Our study shows that nanoparticle assembly is not only a matter of minimizing energy but also of how surface charges evolve dynamically as particles fuse. Competitive ion adsorption creates facet-dependent surface potentials that change over time, generating torques that steer nanoparticles into specific alignments. This explains why oriented attachment can proceed in stages—first along one facet, then another—producing complex architectures.

In summary, we have found a way to guide nanoparticles to build themselves by exploiting the ions competition at their surfaces. This discovery provides a new lever for material design: by programming the solution chemistry, we can arrange the interactions of nanoparticles, opening the door to a new generation of nanostructured materials with customized shapes and functions.

Follow the Topic

-

Nature Communications

An open access, multidisciplinary journal dedicated to publishing high-quality research in all areas of the biological, health, physical, chemical and Earth sciences.

Related Collections

With Collections, you can get published faster and increase your visibility.

Women's Health

Publishing Model: Hybrid

Deadline: Ongoing

Advances in neurodegenerative diseases

Publishing Model: Hybrid

Deadline: Mar 24, 2026

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in