Can Narratives Affect Opinion Polarization?

Published in Behavioural Sciences & Psychology, Arts & Humanities, and Economics

Explore the Research

Narratives and opinion polarization: a survey experiment - Scientific Reports

Scientific Reports - Narratives and opinion polarization: a survey experiment

Our main question

The breakout of the COVID-19 pandemic represents an ideal setting to examine this issue, since in the early days of the pandemic, two prominent stories emerged to explain the origins of the disease. The Lab Narrative essentially suggested that the pandemic originated because of a human error and scientific misconduct in a laboratory in China. The Nature narrative instead described the biological and genetic origin of the disease (without explicitly attributing its cause to human actions). In this context, we conducted a survey experiment on US nationals in the early days of the COVID-19 pandemic (May 2020). Subjects were randomly exposed to one of the two alternative media-based explanations of the origin of the pandemic, to see whether these narratives could influence people’s opinions on both the origin of the pandemic and on three relevant policy issues (i.e., trade openness, climate change, and trust in science) that were not explicitly mentioned by the narratives. Considering these indirect effects allows us to explore whether COVID-19 explanations can evoke wider narratives that have an influence on policy opinions.

Narratives and causes of COVID-19

The respondents were asked to allocate 100 points among four potential causes: the virus was the result of a laboratory accident, the virus originated from a natural process, the virus was a weapon used by countries against each other, and other causes. The greater the number of points assigned to a particular cause, the stronger the belief that a cause is responsible for the emergence of COVID-19.

This result suggests that incremental exposure to one of the two contrasting narratives shifts beliefs in different directions, therefore representing a potential cause for polarization. We refer to this as two-sided polarization by exposure, as both narratives have an impact on beliefs, but in opposite directions.

Figure 1: Bar chart indicating the average points that respondents assigned to the listed causes of COVID-19 and their 95% confidence

Narratives and policy domains

Thus, unlike beliefs regarding the causes of the pandemic, when considering policy opinions, only one narrative has a significant impact on beliefs. We therefore denote this effect of narratives as one-sided polarization by exposure.

Figure 2: This graph shows the marginal effect of the Nature Narrative on the predicted probabilities for each class of response.

Additional results: narratives and the social context

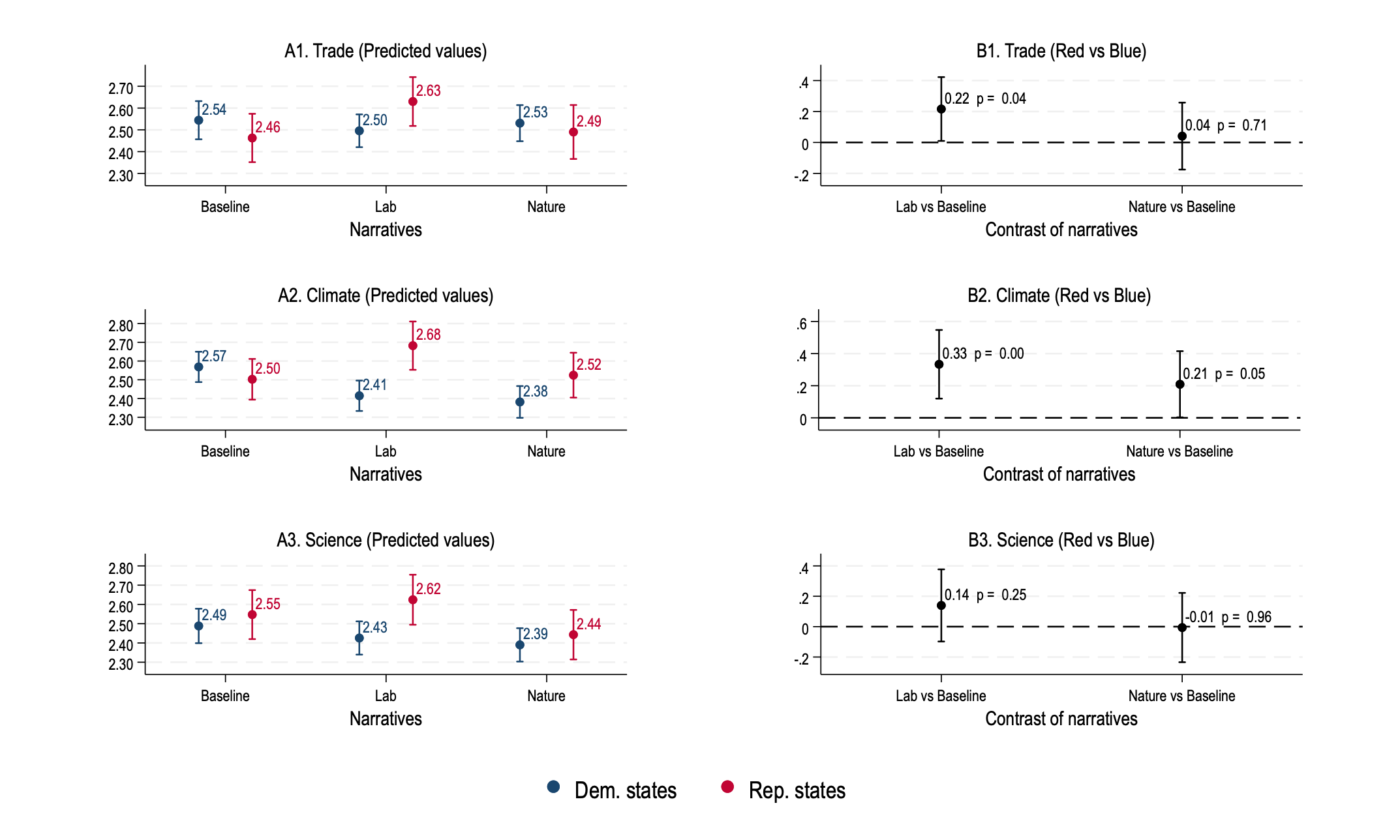

Figure 3: For each treatment group, Panels A1-A3 illustrate the difference in opinions between subjects living in red and blue states. Panels B1-B3 display the causal differential effect of each treatment on the opinion gap between individuals living in red and blue states. Capped spikes indicate the 95% confidence iintervals derived from t-statistics (Panels A1-A3) and chi-square statistics (Panels B1-B3).

1. Eliaz, K. & Spiegler, R. A model of competing narratives. Am. Econ. Rev. 110, 3786–3816 (2020).

2. Media bias and voting. Della Vigna, S. & Kaplan, E. The Fox News effect. Quart. J. Econ. 122, 1187–1234 (2007).

3. Bakshy, E., Messing, S. & Adamic, L. A. Exposure to ideologically diverse news and opinion on facebook. Science 348, 1130–1132 (2015).

4. Levy, R. Social media, news consumption, and polarization: Evidence from a field experiment. Am. Econ. Rev. 111, 831–70 (2021).

5.. Makowsky, M. D. Religion, clubs, and emergent social divides. J. Econ. Behavior Organ. 80, 74–87 (2011).

Follow the Topic

-

Scientific Reports

An open access journal publishing original research from across all areas of the natural sciences, psychology, medicine and engineering.

Related Collections

With Collections, you can get published faster and increase your visibility.

Reproductive Health

Publishing Model: Hybrid

Deadline: Mar 30, 2026

Women’s Health

Publishing Model: Open Access

Deadline: Feb 28, 2026

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in