Capturing microbial dark matter by visualizing them

Published in Microbiology

Ever since Norm Pace and his colleagues began to discover new life forms from mixtures of environmental DNA sequences in the mid-1990s [1], the field of metagenomics has enabled the discovery of large amounts of uncultivable microbial “dark matter”, that has vastly expanded our view of the tree of life. Led by Dr. Sarah Highlander, Ph.D., our team at the J. Craig Venter Institute (JCVI) in La Jolla, CA, had the mission of chasing dark matter that could be pathogenic to humans. Sarah is now the director of the Clinical Microbiome Services Center at Translational Genomics North in Flagstaff, Arizona, and I am a postdoctoral scholar in the laboratory of Dr. Rob Knight, Ph.D. at the Department of Pediatrics, University of California, San Diego.

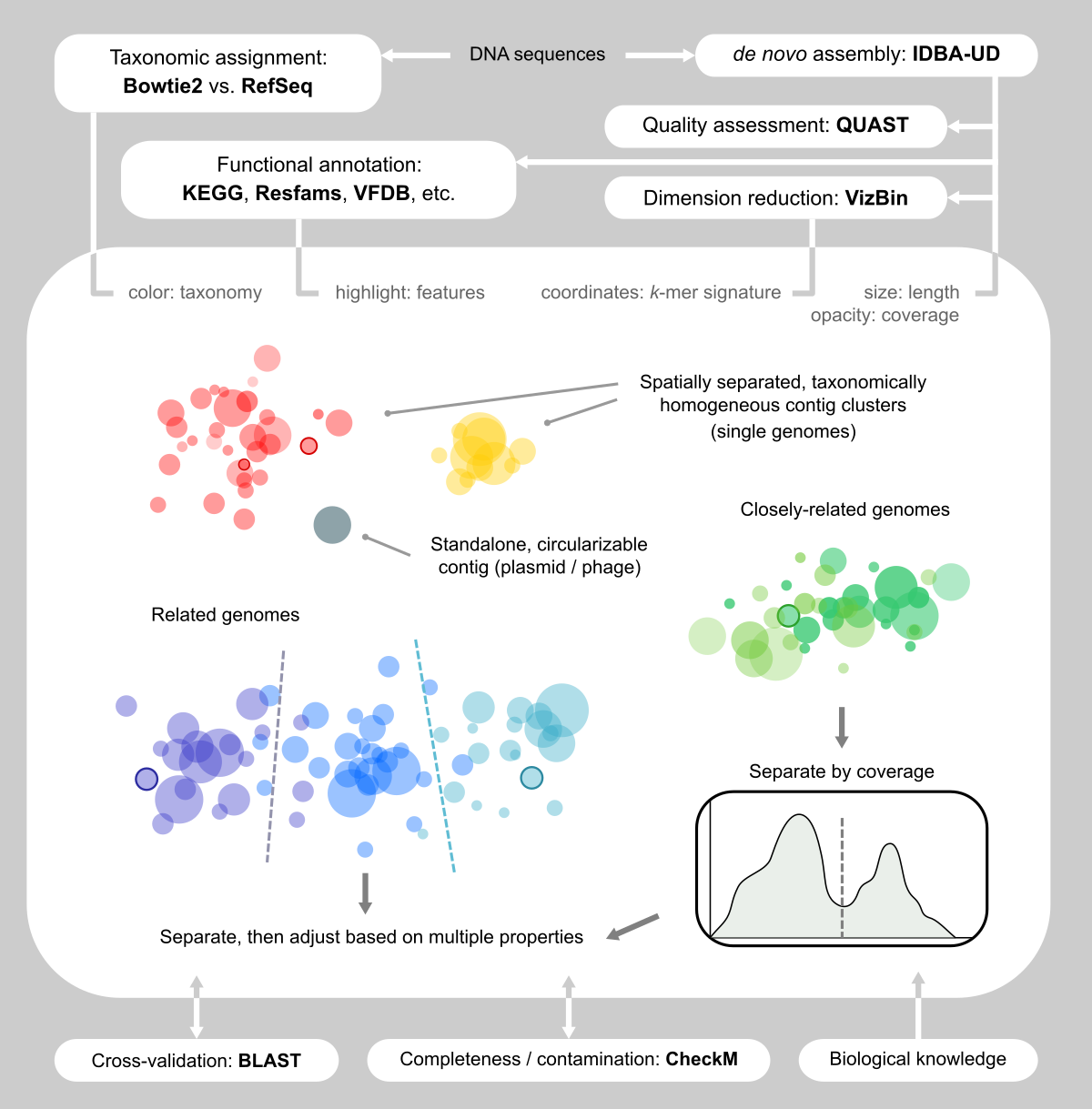

Figure 1. Our visualization-assisted metagenome binning workflow.

We studied traveler’s diarrhea (TD), a disease that is extremely common among international visitors who travel to developing nations. We already knew many of the pathogens that can cause diarrhea, such as enterotoxigenic and enteroaggregative Escherichia coli (ETEC and EAEC), norovirus (NoV), plus a few others. But things got challenging in another 40% of patients who are pathogen-negative in their lab report. We knew that a bacterium was there, because antibiotic treatment usually worked, but we couldn’t always know what the pathogen was.

Those cases were exactly what we were interested in studying. The pathogenic profile of TD patients is likely polymicrobial. Depending on where one travels and what one eats, drinks, and touches, there are multiple opportunities for bugs to enter the body. Our mission was to single them out using sequencing of complete gut metagenomes, using a process referred to as “binning”.

There are multiple automatic binners available. We tested a few popular ones, and were surprised (and disappointed) to find that the results shared low congruence. A more systematic comparison can be found in Sczyrba, et al. [2], which delivers a similar message, especially when the microbial community is complex. In our particular case, two more challenges added to the difficulty: 1) we cared about pathogenic potential, which are usually associated with mobile elements and difficult to associate with their host genome; 2) we couldn’t utilize differential coverage for binning [3], since every sample was unique.

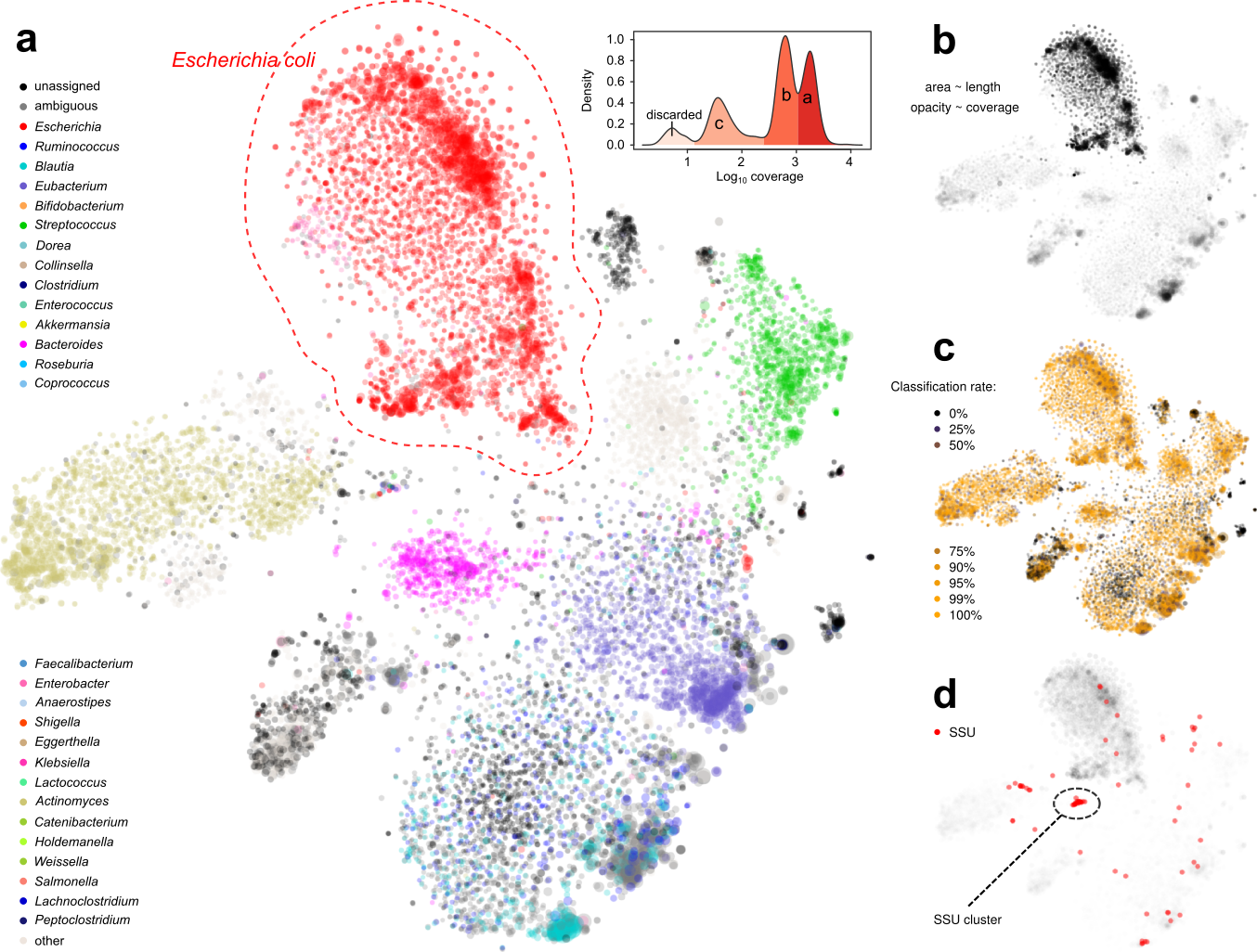

Figure 2. Display of a metagenome assembly and multiple aspects. Each dot represents a contig. a. Coloring by taxonomic assignment. The red circle surrounds a mixture of several E. coli strains, which were further separated by the coverage map (inset). b. Opacity by coverage. b. Brightness by classification rate. d. Mapping SSU rRNA gene(s).

Facing the limitation of facilitating algorithms, we decided to use the “dump” method: that is we eyeballed assemblies and handpicked contigs (Figs. 1 and 2). Sounds like this was tedious and not fun. Yet, as we immersed ourselves into the clouds of contigs, we realized that this was one of the few reliable ways of capturing genomes, because we “saw” them and became convinced that they were there.

We were inspired by VizBin [4], which renders cool scatter plots based on the dimension reduction of k-mer signatures of contigs, and allows the user to draw polygons on the screen to select contigs. We also wanted more information displayed side-by-side (Fig. 2b, c, d) so that we could make better decisions about the validity of a contig clusters. Therefore, we developed our own computational + manual workflow for this task.

Under such a fine-grained microscopic view we were excited to find new patterns. For example, we were able to separate closely-related strains of E. coli, a normal and common component of the gut microbiota and also a potential pathogenic invader, by examining the coverage distribution and functional annotation of contigs. This permitted us to separate and assemble individual E. coli strains within a single metagenomic sample.

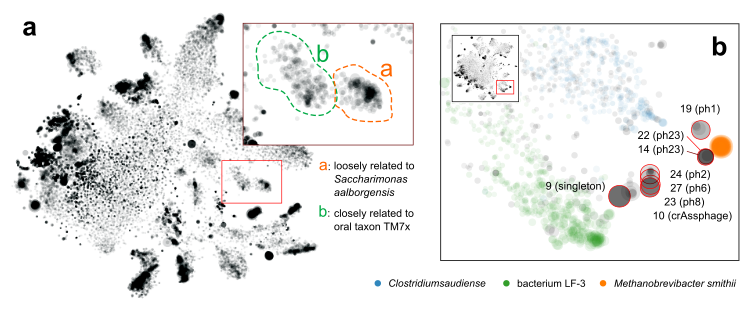

More interestingly, in one sample we separated two blobs of contigs that seem to be related to TM7, a classical “dark matter” bacterial phylum [5]. One mapped to the known oral strain TM7x and this genome was found in several other samples in our cohort (Fig. 3a). The other was “darker” (i.e., more distant from any known species). Further phylogenomic analysis suggested that it was distant from TM7x, but more similar to a strain originally found in wastewater [3]. This now led to plausible explanations regarding this subject during their international trip.

Figure 3. a. separation of a novel TM7 strain (a) from a known one (b). b. Discovery of multiple novel phage genomes related to crAssphage.

Another interesting finding that was only enabled by gazing at graphs, was that multiple samples shared a pattern that multiple, spatially (meaning k-mer signature-wise) proximal contigs with similar sizes. Most of them were single, circular contigs (Fig. 3b). Within each sample, one of them could be perfectly mapped to crAssphage, a 97-kbp, highly abundant bacteriophage that was discovered from human gut microbiome sequences several years ago [6], and was isolated only very recently [7]. The others remained “dark”, without any detectable sequence homology to other organisms, including crAssphage. However, the visual information clearly suggested that there is big family of related viral particles dwelling in our guts. Our findings, together with a recent study [8], significantly expanded this mysterious viral diversity.

This work revealed that in many subjects, multiple pathogenic strains were present. Most of them were E. coli strains, but dark matter genomes, some with putative pathogen genes, were also identified. These would not have been identified by traditional read mapping methods, which speaks to the power of binning.

The publication is available here: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40168-018-0579-0

Zhu, Qiyun, Christopher L. Dupont, Marcus B. Jones, Kevin M. Pham, Zhi-Dong Jiang, Herbert L. DuPont and Sarah K. Highlander. Visualization-assisted binning of metagenome assemblies reveals potential new pathogenic profiles in idiopathic travelers’ diarrhea. Microbiome 6, 201 (2018).

References

- Barns SM, et al. Perspectives on archaeal diversity, thermophily and monophyly from environmental rRNA sequences. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 93, 9188-93 (1996).

- Sczyrba A, et al. Critical assessment of metagenome interpretation—a benchmark of metagenomics software. Nat Methods 14, 1063-71 (2017).

- Albertsen M, et al. Genome sequences of rare, uncultured bacteria obtained by differential coverage binning of multiple metagenomes. Nat Biotechnol 31, 533-8 (2013).

- Laczny CC, et al. VizBin - an application for reference-independent visualization and human-augmented binning of metagenomic data. Microbiome 3, 1 (2015).

- He X, et al. Cultivation of a human-associated TM7 phylotype reveals a reduced genome and epibiotic parasitic lifestyle. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 112, 244-9 (2015).

- Dutilh BE, et al. A highly abundant bacteriophage discovered in the unknown sequences of human faecal metagenomes. Nat Commun 5, 4498 (2014).

- Shkoporov AN, et al. ΦCrAss001 represents the most abundant bacteriophage family in the human gut and infects Bacteroides intestinalis. Nat Commun 9, 4781 (2018).

- Yutin N, et al. Discovery of an expansive bacteriophage family that includes the most abundant viruses from the human gut. Nat Microbiol 3, 38–46 (2018).

Follow the Topic

-

Microbiome

This journal hopes to integrate researchers with common scientific objectives across a broad cross-section of sub-disciplines within microbial ecology. It covers studies of microbiomes colonizing humans, animals, plants or the environment, both built and natural or manipulated, as in agriculture.

Related Collections

With Collections, you can get published faster and increase your visibility.

Harnessing plant microbiomes to improve performance and mechanistic understanding

This is a Cross-Journal Collection with Microbiome, Environmental Microbiome, npj Science of Plants, and npj Biofilms and Microbiomes. Please click here to see the collection page for npj Science of Plants and npj Biofilms and Microbiomes.

Modern agriculture needs to sustainably increase crop productivity while preserving ecosystem health. As soil degradation, climate variability, and diminishing input efficiency continue to threaten agricultural outputs, there is a pressing need to enhance plant performance through ecologically-sound strategies. In this context, plant-associated microbiomes represent a powerful, yet underexploited, resource to improve plant vigor, nutrient acquisition, stress resilience, and overall productivity.

The plant microbiome—comprising bacteria, fungi, and other microorganisms inhabiting the rhizosphere, endosphere, and phyllosphere—plays a fundamental role in shaping plant physiology and development. Increasing evidence demonstrates that beneficial microbes mediate key processes such as nutrient solubilization and uptake, hormonal regulation, photosynthetic efficiency, and systemic resistance to (a)biotic stresses. However, to fully harness these capabilities, a mechanistic understanding of the molecular dialogues and functional traits underpinning plant-microbe interactions is essential.

Recent advances in multi-omics technologies, synthetic biology, and high-throughput functional screening have accelerated our ability to dissect these interactions at molecular, cellular, and system levels. Yet, significant challenges remain in translating these mechanistic insights into robust microbiome-based applications for agriculture. Core knowledge gaps include identifying microbial functions that are conserved across environments and hosts, understanding the signaling networks and metabolic exchanges between partners, and predicting microbiome assembly and stability under field conditions.

This Research Topic welcomes Original Research, Reviews, Perspectives, and Meta-analyses that delve into the functional and mechanistic basis of plant-microbiome interactions. We are particularly interested in contributions that integrate molecular microbiology, systems biology, plant physiology, and computational modeling to unravel the mechanisms by which microbial communities enhance plant performance and/or mechanisms employed by plant hosts to assemble beneficial microbiomes. Studies ranging from controlled experimental systems to applied field trials are encouraged, especially those aiming to bridge the gap between fundamental understanding and translational outcomes such as microbial consortia, engineered strains, or microbiome-informed management practices.

Ultimately, this collection aims to advance our ability to rationally design and apply microbiome-based strategies by deepening our mechanistic insight into how plants select beneficial microbiomes and in turn how microbes shape plant health and productivity.

This collection is open for submissions from all authors on the condition that the manuscript falls within both the scope of the collection and the journal it is submitted to.

All submissions in this collection undergo the relevant journal’s standard peer review process. Similarly, all manuscripts authored by a Guest Editor(s) will be handled by the Editor-in-Chief of the relevant journal. As an open access publication, participating journals levy an article processing fee (Microbiome, Environmental Microbiome). We recognize that many key stakeholders may not have access to such resources and are committed to supporting participation in this issue wherever resources are a barrier. For more information about what support may be available, please visit OA funding and support, or email OAfundingpolicy@springernature.com or the Editor-in-Chief of the journal where the article is being submitted.

Collection policies for Microbiome and Environmental Microbiome:

Please refer to this page. Please only submit to one journal, but note authors have the option to transfer to another participating journal following the editors’ recommendation.

Collection policies for npj Science of Plants and npj Biofilms and Microbiomes:

Please refer to npj's Collection policies page for full details.

Publishing Model: Open Access

Deadline: Jun 01, 2026

Microbiome and Reproductive Health

Microbiome is calling for submissions to our Collection on Microbiome and Reproductive Health.

Our understanding of the intricate relationship between the microbiome and reproductive health holds profound translational implications for fertility, pregnancy, and reproductive disorders. To truly advance this field, it is essential to move beyond descriptive and associative studies and focus on mechanistic research that uncovers the functional underpinnings of the host–microbiome interface. Such studies can reveal how microbial communities influence reproductive physiology, including hormonal regulation, immune responses, and overall reproductive health.

Recent advances have highlighted the role of specific bacterial populations in both male and female fertility, as well as their impact on pregnancy outcomes. For example, the vaginal microbiome has been linked to preterm birth, while emerging evidence suggests that gut microbiota may modulate reproductive hormone levels. These insights underscore the need for research that explores how and why these microbial influences occur.

Looking ahead, the potential for breakthroughs is immense. Mechanistic studies have the power to drive the development of microbiome-based therapies that address infertility, improve pregnancy outcomes, and reduce the risk of reproductive diseases. Incorporating microbiome analysis into reproductive health assessments could transform clinical practice and, by deepening our understanding of host–microbiome mechanisms, lay the groundwork for personalized medicine in gynecology and obstetrics.

We invite researchers to contribute to this Special Collection on Microbiome and Reproductive Health. Submissions should emphasize functional and mechanistic insights into the host–microbiome relationship. Topics of interest include, but are not limited to:

- Microbiome and infertility

- Vaginal microbiome and pregnancy outcomes

- Gut microbiota and reproductive hormones

- Microbial influences on menstrual health

- Live biotherapeutics and reproductive health interventions

- Microbiome alterations as drivers of reproductive disorders

- Environmental factors shaping the microbiome

- Intergenerational microbiome transmission

This Collection supports and amplifies research related to SDG 3, Good Health and Well-Being.

All submissions in this collection undergo the journal’s standard peer review process. As an open access publication, this journal levies an article processing fee (details here). We recognize that many key stakeholders may not have access to such resources and are committed to supporting participation in this issue wherever resources are a barrier. For more information about what support may be available, please visit OA funding and support, or email OAfundingpolicy@springernature.com or the Editor-in-Chief.

Publishing Model: Open Access

Deadline: Jun 16, 2026

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in