Carving up the tropics for dinner

Published in Ecology & Evolution

This story starts with a minor heart attack. OK, not literally, but you know that feeling – when you come across a new publication and it has single-handedly achieved what you were planning to do – but better.

Welcome to my office in the cold Berlin spring of 2015. I was in the middle of my PhD focused on the nexus of growing food and conserving fauna. I was particularly interested in how land-use change in the form of intensification and expansion can influence biodiversity patterns.

The beautiful new Nature paper that gave me these panicked palpitations two years ago was entitled “Global effects of land use on local terrestrial biodiversity”. I knew from the title my research plans were in danger. What Newbold and his colleagues did was nothing short of gargantuan. Through an ongoing project named PREDICTs, they brought together thousands of datasets and over a million data points from across the globe to model the impacts of various forms of land-use on biodiversity. The plans for my research were scuppered.

Some of my first thoughts. Calming sunset photo from Pixabay.com

I am a conservation researcher not primarily for the scientific thrills or the modelling nuances but for the sake of conservation itself. So when something comes out that does a far better job of what I am planning, once I get past the initial shock and panic, I am actually quite happy about it. It means the field is moving forward and we can tackle deeper questions. This Nature paper presented the largest and most refined picture we currently have on the effects of land-use on wildlife, and it opened the door to our current publication on the potential future impacts of agricultural development on biodiversity.

We first developed a 1km2 land systems map encompassing all current cropland and livestock along an intensity gradient and including a distinction between remaining arable areas that have not yet been farmed and those that cannot be farmed due to biophysical restraints (see doi below for freely available data download).

We then linked this to the extensive database of biodiversity responses to agriculture (the one that gave me the minor heart attack). Together, this allowed us to identify high-risk regions in terms of potentially high biodiversity loss. Low national conservation spending, and high agricultural growth were also assessed in order to identify countries most at risk.

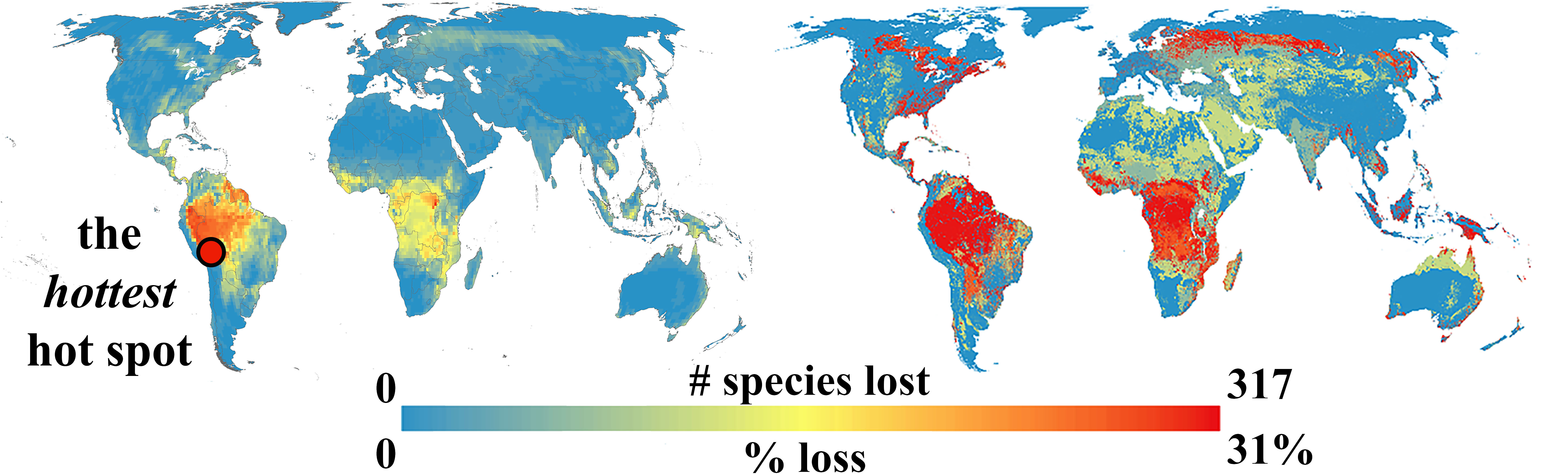

Map shows the potential biodiversity loss due to agricultural expansion and intensification and the resulting number of species lost per grid cell (left panel) and percentage decline in abundance (right panel).

We found up to one third of species richness and abundance could be potentially lost due to expansion and intensification across the Amazon and Afrotropics. For example, deforestation driven by soy feed for livestock is already widespread across Latin America and growing in other regions.

Sub-Saharan Africa was found to be particularly susceptible. It is in the crossroads of demographic and agricultural growth, therefore making the minimization of the impacts of agricultural change an urgent challenge. Compared to Latin America, Sub-Saharan Africa has only half the protected area coverage of areas at-risk of farmland expansion (21% and 43% respectively).

Considering rising agricultural demand, we highlight areas where timely land-use planning may proactively mitigate biodiversity loss. Our work supports calls to include potential future land-use change in conservation prioritization schemes.

Thanks to Newbold and co and everybody that contributed to both the PREDICTs project and more refined land-use data, we can now better assess where and how biodiversity will be under threat in the future. We hope our work can contribute to ongoing initiatives to proactively prevent wildlife decline.

The paper in Nature Ecology & Evolution is here: http://go.nature.com/2uqdL2K

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in