Cats love fish, don’t they?

Published in Ecology & Evolution

An estimated 6% of all fish caught today are used to produce cat food, and cat owners have no doubt noticed how eager their beloved pets are to eat fish offered to them. Yet, although domestic cats take home a wide variety of birds and small mammals, they rarely catch fish, a phenomenon that has also been observed in feral and wild cats. Since cats are opportunistic hunters, consumption of fish and larger mammals that they cannot catch themselves will occur when they live in or close to a human environment where they can more easily access this food. Direct observation of hunting cats or analysis of stomach contents make it possible to reconstruct the diet of modern animals.

In archaeology, such dietary studies initially focussed on human bones, but gradually also animals – both wild and domestic – were analysed. Of the carnivores, dogs have so far received the most attention, while cats have only rarely been analysed, mainly because the number of their relatively small bones found in excavations is quite limited. The paucity of cat remains may also be a reason why its domestication history has been much less investigated compared to other popular domestic animals (e.g. dog, horse, livestock). An ongoing EU-funded project, called ‘Felix. Genomes, food and microorganisms in the (pre)history of cat-human interactions’ (https://www.ercfelix.com/) aims to unravel the relationship between humans and cats in the past from different perspectives. For this, we have at our disposal numerous bones, teeth and even some hair and claws from a total of more than 800 individuals dating from more than 10,000 years ago until the 18th and 19th centuries from archaeological sites in Europe, Southwest Asia and North Africa.

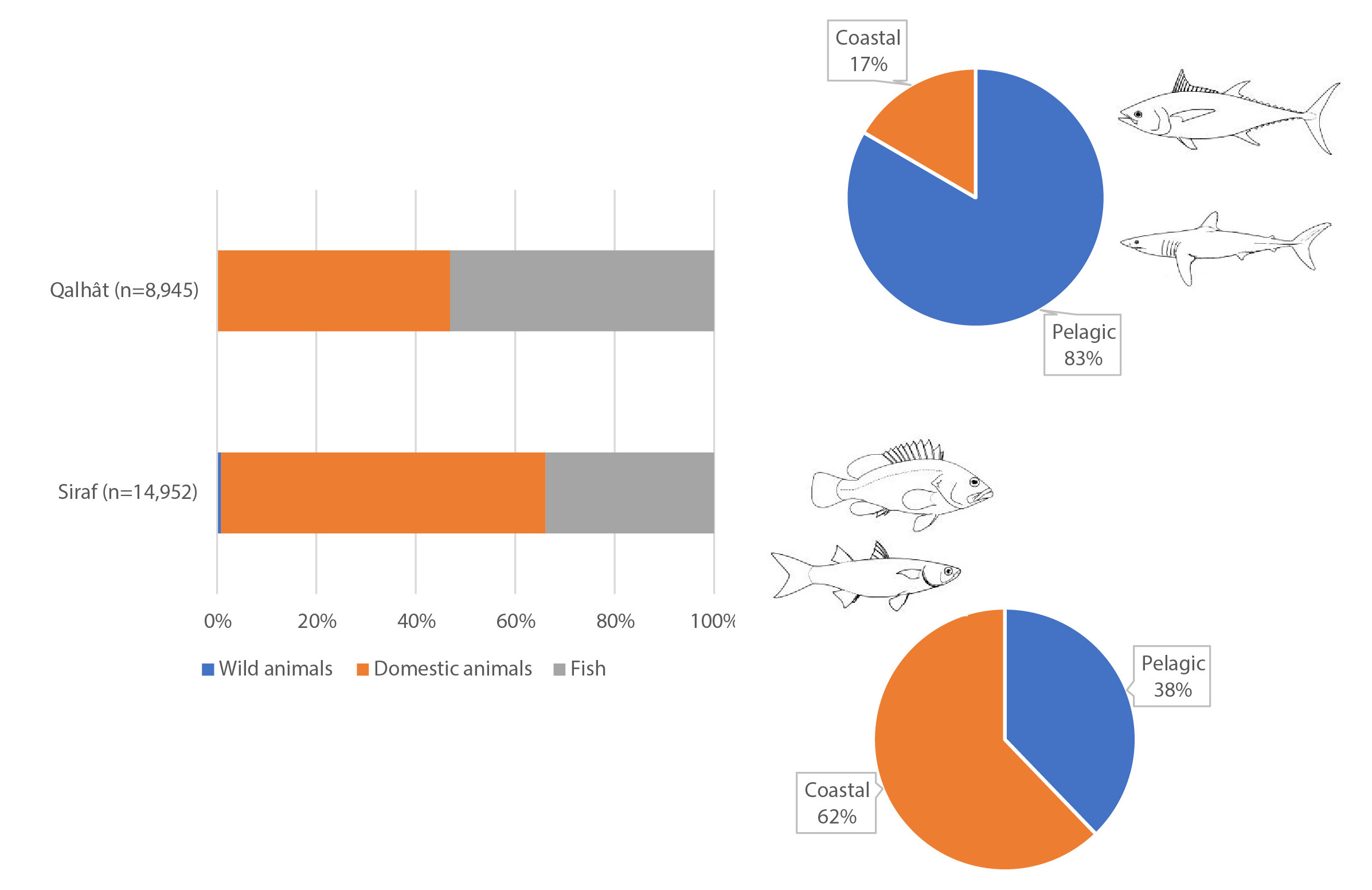

To contribute to the 'food history' of cats, we selected bones from two medieval ports in Southwest Asia, Qalhât, in Oman, and Siraf, in southern Iran. A key feature of these sites is that not only numerous cat bones are available for analysis, but tens of thousands of other animal bones have also been studied before. Previous research on food waste made it possible to reconstruct the diet of humans during the Middle Ages, hence what would have been theoretically available for cats to eat or scavenge.

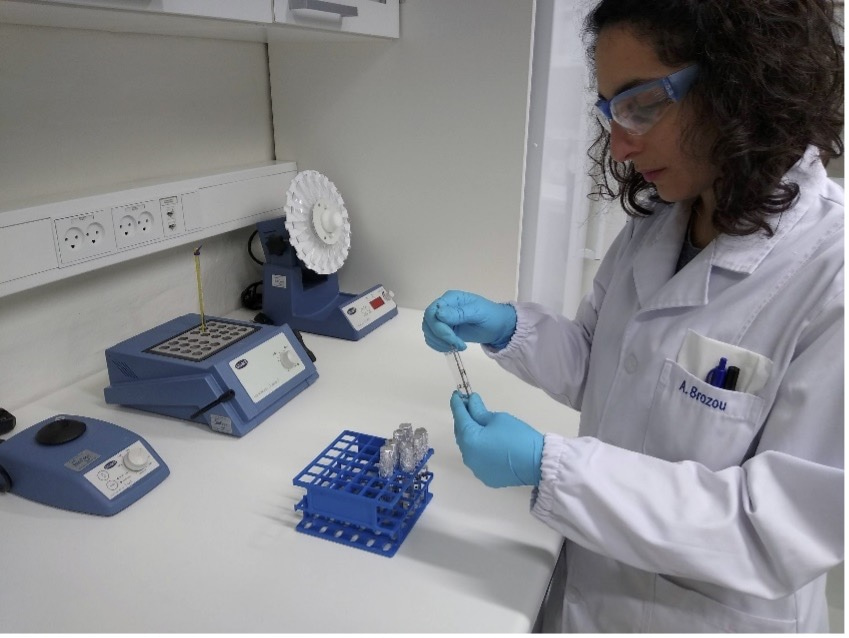

Anastasia Brozou processing bone collagen samples in the stable isotope lab of the Division of Soil and Water Management of the University of Leuven.

Not surprisingly given the coastal position of these sites, a heavy reliance on fish in the human diet was observed. Hence, we were expecting to obtain a very clear signal of fish in the carbon and nitrogen stable isotope results for the cats too. This was indeed the case for the cats from Qalhât that showed a very strong marine signal in the collagen of their bones. In fact, the values are the most elevated ever seen in hundreds of cats that we have so far analysed from other sites in our wide study region. The explanation lies in the fact that fish was no doubt an important part of their diet, but in particular in the fact that the majority of the fish landed at Qalhât were large pelagic species such as tunas and sharks.

An archaeologist working at the site told us that at the landing places along the Omani coast fishermen typically gut these large fish and that the entrails attract numerous cats. The medieval cats from Qalhât were likely stray animals that survived by scavenging on fish offal and it appears from the numerous pathologies on their bones that they were not in very good health.

Group of harbour cats in Bahrain, 2005 (credit: Adele O’Shea)

Follow the Topic

-

Scientific Reports

An open access journal publishing original research from across all areas of the natural sciences, psychology, medicine and engineering.

Related Collections

With Collections, you can get published faster and increase your visibility.

Reproductive Health

Publishing Model: Hybrid

Deadline: Mar 30, 2026

Obesity

Publishing Model: Hybrid

Deadline: Apr 24, 2026

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in