Chasing hummingbirds in the footsteps of Humboldt

Published in Ecology & Evolution

The Andes are a hotspot for biodiversity, where thousands of species have evolved and thrive today. This richness inspired Alexander von Humboldt’s ideas about nature, and how we are all interconnected. Just like the Andes were crucial for Humboldt’s work, they continue shaping our understanding of ecology, evolution, and biogeography. Its great diversity inspires scientists to make fascinating discoveries like the one my collaborators and I made about hummingbird communication.

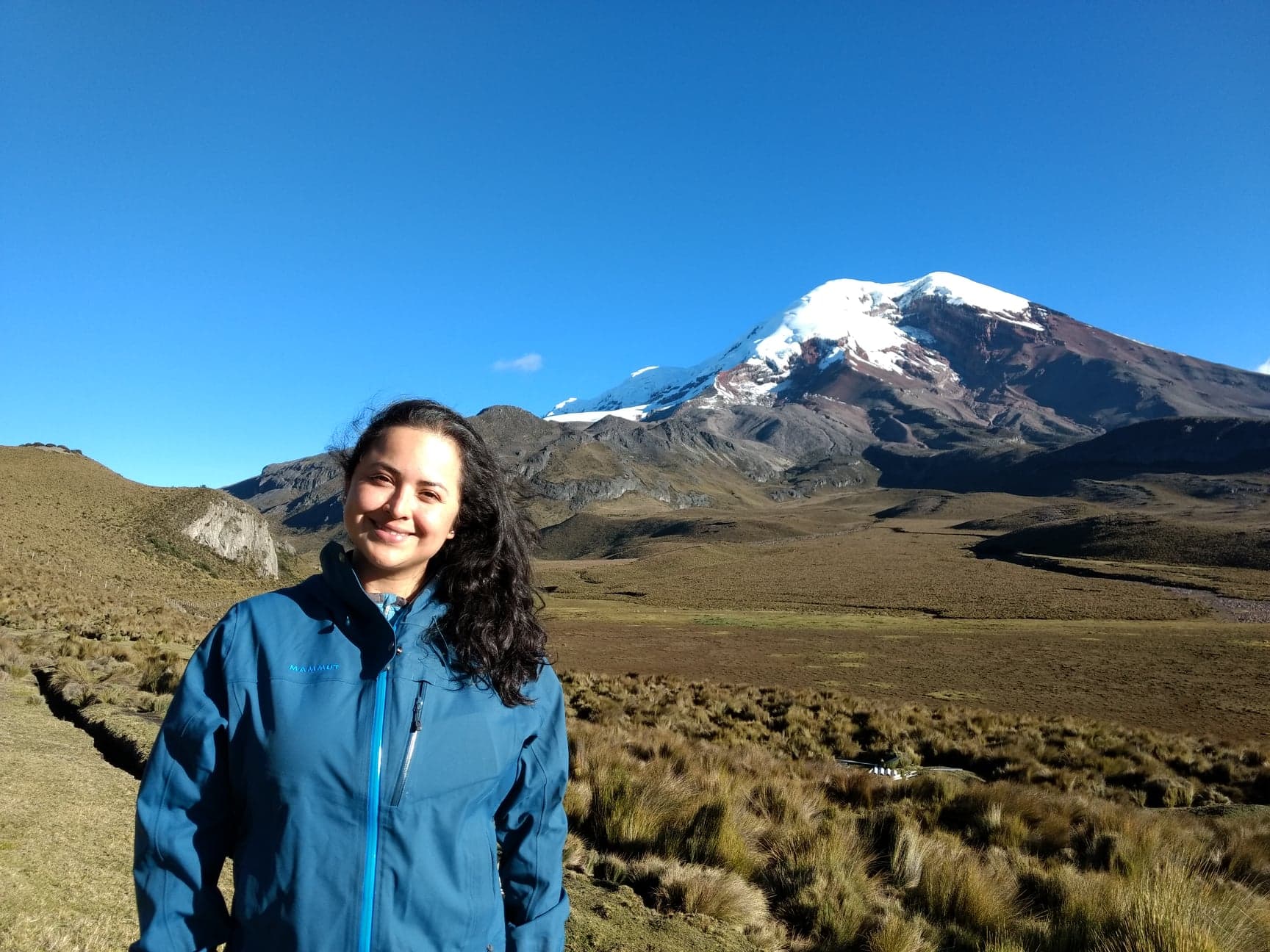

Fernanda G. Duque at the skirts of Mt. Chimborazo during a field trip to study high-frequency vocalizations in the Ecuadorian Hillstar (Oreotrochilus chimborazo). Photo: Patricia Chanaba.

I am an Ecuadorian PhD candidate in Neuroscience at Georgia State University studying vocal communication in hummingbirds. My dissertation focuses on understanding the evolution of high-frequency vocalizations in these birds. These high-pitched sounds that only some species of hummingbirds produce have frequencies above those that scientists thought any bird could hear. I investigate ecological aspects of these vocalizations, their function in social behavior, and the neural components associated with this adaptation.

In 2018, my collaborators and I published a study in Current Biology reporting the discovery of high-frequency vocalizations in four species of Andean hummingbirds. Three species live in the cloud forest (Adelomyia melanogenys, Boissonneaua flavescens, and Aglaiocercus coelestis) and the fourth species (Oreotrochilus chimborazo) is native to the high-altitude grasslands or paramo. We also showed that the frequency content of these calls does not overlap with the ambient noise in their habitat, suggesting that these high-frequency vocalizations are adapted to the challenging acoustic conditions in their environment.

Adult male Ecuadorian Hillstar (Oreotrochilus chimborazo) near Quilotoa Volcano (Ecuador) perching atop a Chuquiraga j. branch. Photo: Fernanda G. Duque

The story of this discovery began many years ago with one hummingbird, the Ecuadorian Hillstar (O. chimborazo). This is a high-altitude specialist distributed along the Andean paramos of Ecuador and southern Colombia. Carlos Rodriguez-Saltos, my collaborator, worked with this hummingbird a decade ago, looking at the genetic diversity across populations of the species. Sometimes he heard ‘weird’ sounds which he suspected were produced by the hummingbirds. On January 02, 2014 we went on a search for the Ecuadorian Hillstar, climbed Mt. Pichincha near Quito, and obtained our first recording of a high-frequency vocalization from the hummingbird. When we analyzed the recording, we knew we were onto something!

At the time, however, Carlos was in the United States pursuing his PhD, and I had a full-time job and was preparing to apply for graduate school. A year went by, and we decided that this discovery was too interesting to let it sit any longer. And so, we embarked in our own research adventure. We did not have any research funding at the time, so we made a fund with our savings, bought equipment, and planned expeditions via skype. I, then, went to these field sites with my brother on weekends.

Recording hummingbird vocalizations in the Ecuadorian cloud forest as part of the work that lead to the discovery of three more species of hummingbirds that vocalize at high frequencies in the cloud forest. Photo: Carlos A. Rodriguez-Saltos.

When I entered graduate school in 2016, one of my advisors, Walter Wilczynski proposed that I continue working on this project as my PhD dissertation. From there, our research gained momentum. I initially wondered whether there were other hummingbirds also producing high-pitched calls and went on a quest to document hummingbird vocalizations in different habitats. I discovered high-pitched calls in three more species of hummingbirds in the cloud forest in Ecuador. Finding these calls in the cloud forest was a surprise. High-pitch sounds do not transmit well in densely vegetated environments, so it seemed counter intuitive to find these vocalizations in this habitat. A similar finding was reported on a Brazilian hummingbird living in the lowland forest.

Adult female and juvenile male Ecuadorian Hillstar at Cotopaxi. Photo: Martin Santacruz and Fernanda G. Duque.

Among all the species in which high-pitched vocalizations have been described, the Ecuadorian Hillstar produces the highest frequencies and the most complex song, which is opening a door for us to study social interactions among hummingbirds. Complex songs are usually associated with complex social behaviors; in this case, we are studying the dual function of the song in territoriality and courtship. Andean hummingbirds constitute a good model to study the evolution of vocal communication because of their recent divergence and dispersion into diverse habitats. These features allow us to investigate how hummingbirds have adapted to challenging environmental conditions and developed diverse vocal signals as part of their social behavior.

Just like the Andes shaped many of Humboldt’s views about nature, these mountains are also shaping my own career in science and my perspective in behavioral ecology and neuroethology as I follow in Humboldt's footsteps.

I want to give a special thanks to my advisors Walt Wilczynski and Laura Carruth, my collaborators Carlos Rodriguez-Saltos and Elisa Bonaccorso, and to the many people in Ecuador that help me make this work possible.

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in