Children across societies punish unfairness

Published in Behavioural Sciences & Psychology

Late from your last meeting, you are rushing to the free lunch where your favorite meal is on offer: burritos. Unfortunately, you’re the last in line. Fortunately, there are two burritos left and only one person in front of you. Much to your surprise, the person in front takes both burritos, putting the second burrito in her bag. It’s hard not to feel a certain amount of surprise and indignation at this selfish act. It’s just so unfair—why did she take both?

One of the most striking things about our sense of fairness is that to feel this kind of indignation, we don’t have to be the victims of unfairness ourselves. Just watching one person behave selfishly toward another is enough to activate a strong fairness response and, sometimes, is even enough to prompt observers to take action against the selfish agent by punishing them.

Punishment by observers rather than victims is known as third-party punishment. Studies of adults have shown that third parties who witness one agent acting unfairly toward another are willing to intervene to punish the unfair agent. Moreover, third parties are willing to do so even when they have to give up some of their own resources to punish, showing so-called costly third-party punishment. Work with adults across cultures suggests that costly third-party punishment of unfairness is widespread across human societies, highlighting just how much people across societies care about fairness.

Work with adults across societies has pointed to an exciting hypothesis: Perhaps the third-party punishment of unfairness is part of the foundational human toolkit of behavioral responses to wrongdoing. However, to provide a strong test of this hypothesis, we need additional data. Data from children across different countries is especially valuable in this regard: if we see that a behavior emerges relatively early in development in children across diverse cultures, that gives us some evidence that the behavior is a core part of being human. In the study we just published in Communications Psychology, our team asked whether children across societies would be willing to punish others for unfairness. Following the logic outlined above, we reasoned that evidence for third-party punishment in children across societies would suggest that a strong concern for fairness is deeply rooted in human behavior.

What did we do?

We tackled this question by conducting a study with over 500 5- to 15-year-olds across 6 diverse cultural contexts: Canada, India, Peru, Uganda, USA, and Vanuatu. We introduced our child participants to two other absent children of their age: the so-called divider could decide how to split up six pieces of candy between themselves and a peer. Here comes the key part of the study. After learning about the divider’s decisions, participants got to make a choice. They could either accept the divider’s decision, in which case the divider and the peer got candies according to whatever distribution the divider had settled on. Or, they could reject the decision, in which case neither child got any candy. In this way, participants could punish dividers for making offers that they deemed unacceptable. To add one more twist, we varied whether such punishment was free or whether participants had to pay a cost to punish by giving up one of their own candies. Would children be willing to punish despite the costs?

What did we find?

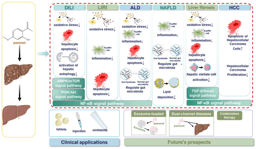

We found that children across all countries punished unfair sharing. Children were more likely to intervene against the divider’s selfish sharing decisions than against equal sharing (Poster image above). Moreover, children punished selfishness even when they had to give up their own candies. These findings suggest that a strong concern for fairness—as indexed by willingness to punish as third parties—is seen across diverse cultural contexts. These data are exciting in their own right because they suggest that from relatively early in childhood, we humans are willing to stand up for fairness even when we’re not the victims of unfairness. And what’s more, our data align with other work showing similar patterns of findings by Bailey House and colleagues who studied children in other parts of the world. This is exciting because conceptual replications of cross-cultural developmental work are rare, in large part due to the challenging logistics of conducting this kind of work.

So, what makes this kind of work so challenging?

Teamwork makes the dream work

There are a number of hurdles to overcome in conducting cross-cultural work. Which populations can we work with? How can we design a task that makes sense to children across different cultures? Who is best-positioned to work directly with children so that the study feels comfortable? Thankfully, many of these hurdles can be overcome by working with a great team, which we were fortunate enough to do in this study. Our team involved 11 authors from 5 different countries, ranging in career stages from recent high school graduates and undergraduate students to tenured professors and organization directors. Our team brought a diverse set of experiences to bear on our project. Completing data collection for this project depended on regular communication, strong long-term relationships, local expertise, and a great deal of patience.

The challenges associated with cross-cultural developmental work are part of what makes it so rewarding. Moreover, this kind of work is crucial to addressing a pressing gap: work in psychology generally and developmental psychology specifically is heavily biased toward populations in the Global North. To contribute to a fuller picture of human development, we simply must explore child development across diverse societies.

Poster image description: The image in the top right corner shows the fair (equal) and unfair (selfish) divider decisions that participants were responding to. The bar plots over each region label show children’s punishment of fair versus unfair decisions across the six different countries.

Follow the Topic

-

Communications Psychology

An open-access journal from Nature Portfolio publishing high-quality research, reviews and commentary. The scope of the journal includes all of the psychological sciences.

Related Collections

With Collections, you can get published faster and increase your visibility.

Intensive Longitudinal Designs in Psychology

Publishing Model: Open Access

Deadline: Mar 31, 2026

Replication and generalization

Publishing Model: Open Access

Deadline: Dec 31, 2026

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in