Uncovering past wildfire dynamics in eastern Siberia: From fieldwork to publication

Published in Earth & Environment and Ecology & Evolution

This post was co-written by Izabella Baisheva and Ramesh Glückler, representing both the Sakha and German sides of this collaborative research effort.

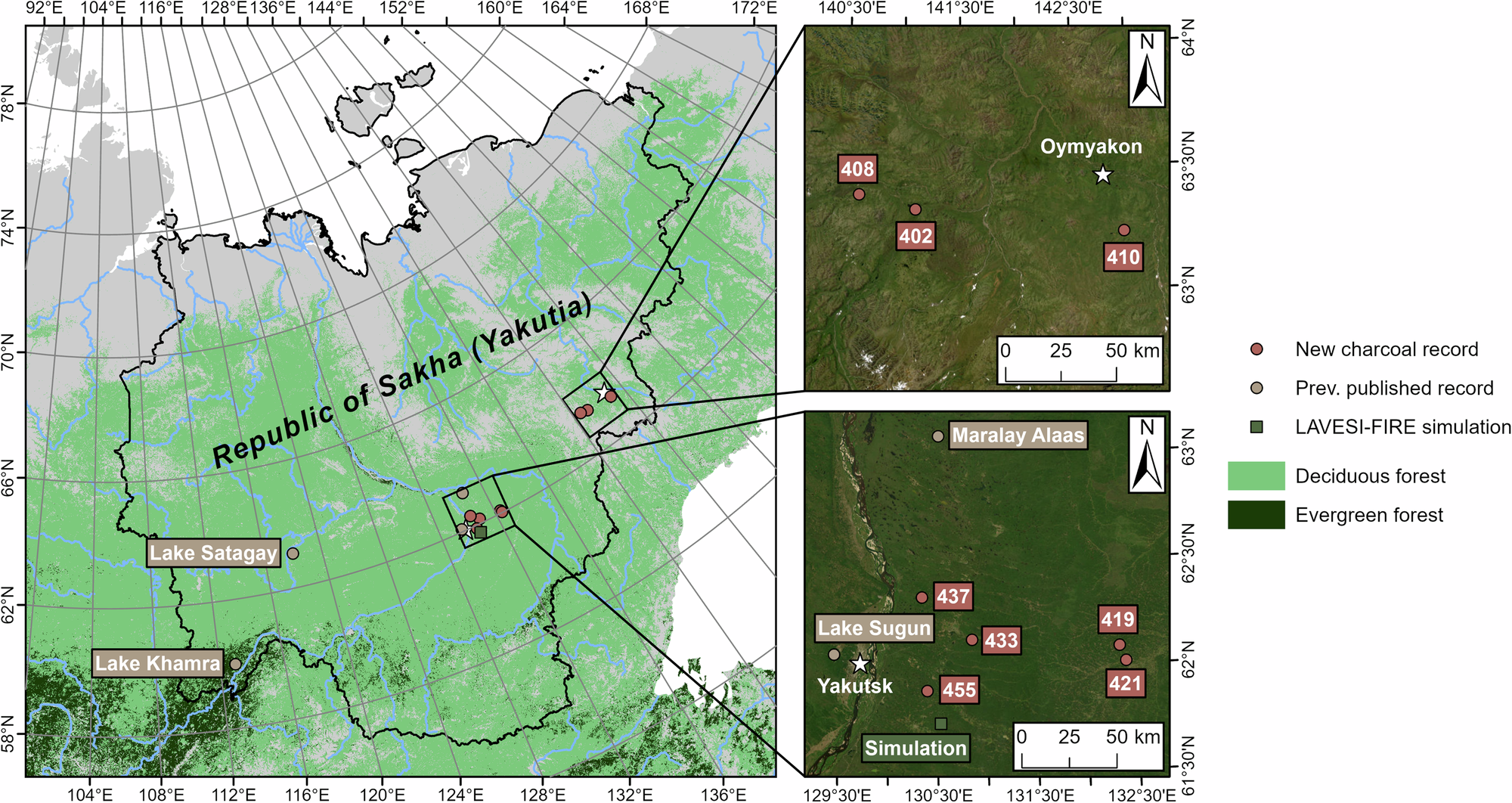

Wildfire regimes in the world's boreal forests are intensifying with climate change, directly putting local communities at risk and indirectly affecting millions more through the continental-scale spread of hazardous smoke plumes. Satellite observations provide valuable data for investigations of wildfire activity over the most recent decades. However, in order to understand long-term wildfire dynamics and its drivers, paleoecological methods are required. Lake sediments represent a natural archive, capturing fire proxies such as charcoal particles and thus recording fire history over centuries and millennia. Research papers tend to break down the work behind paleoecological fire reconstructions to few short paragraphs in a methods section, but a lot of effort has to go into these kinds of data from natural archives. In this post, we want to highlight some of this effort in a bit more detail. With one goal being the reconstruction of Holocene wildfire dynamics in the vast Republic of Sakha (Yakutia), eastern Siberia, we conducted fieldwork in the summer of 2021 - which would turn out to become the most extreme fire season in this region on record.

Those of us arriving from abroad could already smell the fires once stepping out of the airplane in Yakutsk, the republic's capital. During the next few days of preparations at the North-Eastern Federal University of Yakutsk (NEFU), the sun always remained slightly concealed behind a layer of smoke. Besides the lake sediment sampling tools and accessories, field laboratory equipment, spare parts, tents, bear safety gear, provisions, and safety instructions, we also prepared an emergency plan for wildfires. Once everything was organized and packed into our trucks, we left the city, crossing the Lena River by ferry, and heading eastwards to the lakes we aimed to core. Our ride along the dusty Kolyma Highway was interrupted by dense smoke plumes from the wildfires raging in Central Yakutia at the time, plunging the surrounding landscape into apocalyptic shades of brown and orange by day (Figure 1) and generating a red glow by night. We also came by stretches of forest that were burned earlier in the season, and witnessed some of the impacts on local communities, such as road closures or destroyed power lines (Figure 2). We eventually made our way across the Aldan River and to the southern Verkhoyansk Mountains, setting up camp to obtain sediment cores from some of the more remote lakes of this region.

Fieldwork is an exciting part of paleoecological research, yet it can simultaneously be quite demanding. Lots of equipment, including heavy sediment corers and sturdy inflatable boats, had to be brought to the lakes. Sediment cores were extracted by hammering the coring device, containing a liner tube, into the sediment, then carefully pulling it out and manually lifting it up to the boat (Figure 3). The sediment cores needed to be sealed and, back at the camp, tightly packed for transport and storage. Since preparations for the next field day also needed to be done at the camp in parallel to housekeeping and maintenance, activities could stretch long into the night. Over the next weeks we worked in this pattern while backtracking towards Yakutsk, solving the occasional problem such as a truck stuck in the mud or punctures in our boats, repeatedly breaking down camp and setting it up anew, eventually coring lakes in the more densely inhabited region of Central Yakutia.

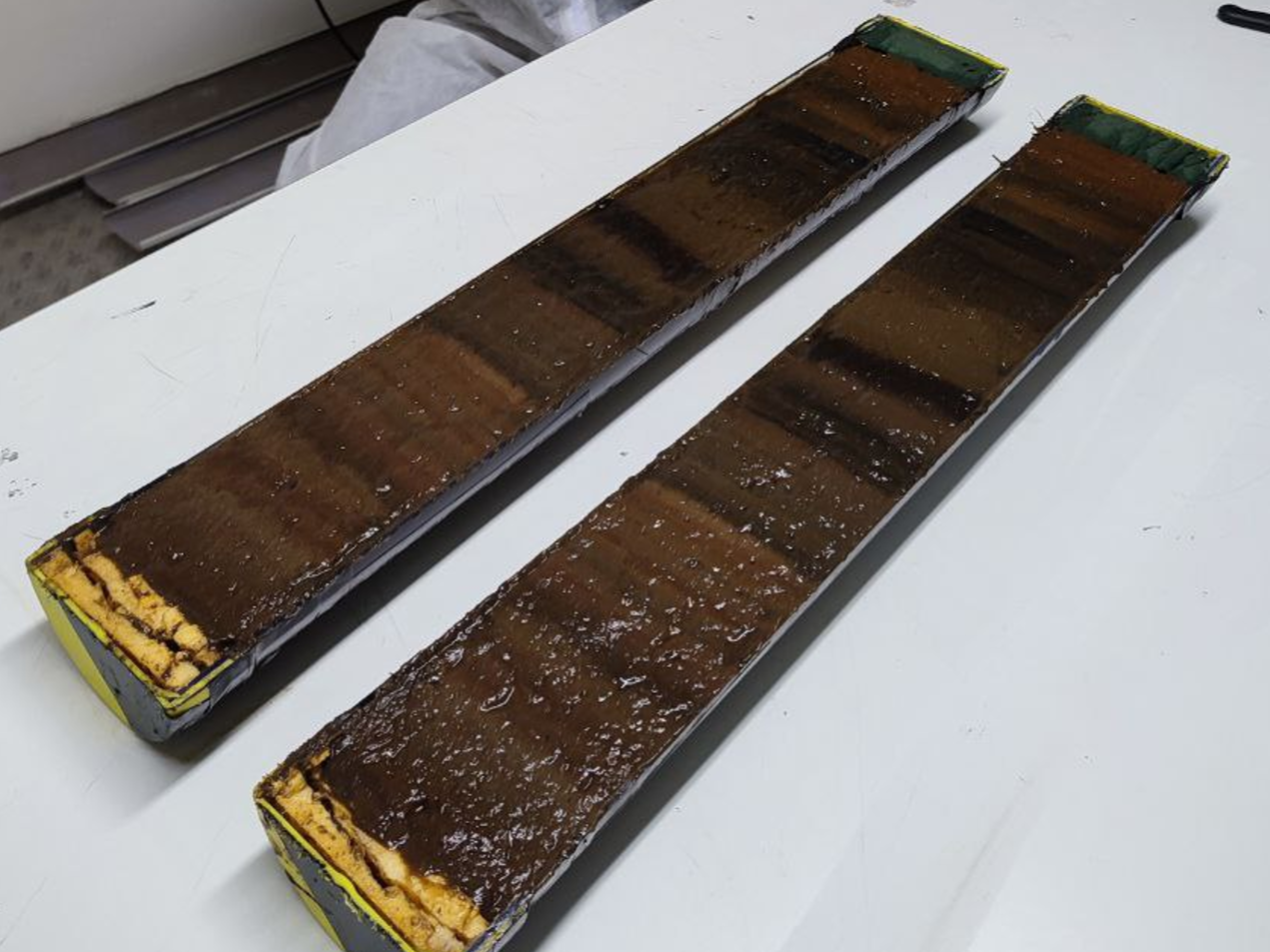

The fruits of this hard work were, among many other samples, measurements, and observations, a total of 126 sediment cores from 56 lakes. Back at NEFU, we logged and stored all cores and other samples, and digitized their metadata recorded in our field notebooks. Later, our colleagues shipped the cores to the Alfred Wegener Institute, Helmholtz Centre for Polar and Marine Research (AWI) in Potsdam, Germany, for subsequent analyses. We selected the most suitable set of sediment cores and then opened and split them length-wise in the laboratory, before contiguous subsampling could begin (Figure 4). Protocols for these procedures vary across the research community and necessitate careful planning and organization. The subsampling routine required weeks of work in a cooled underground climate chamber, kindly supported by students and colleagues, to produce a set of hundreds of samples for subsequent analyses.

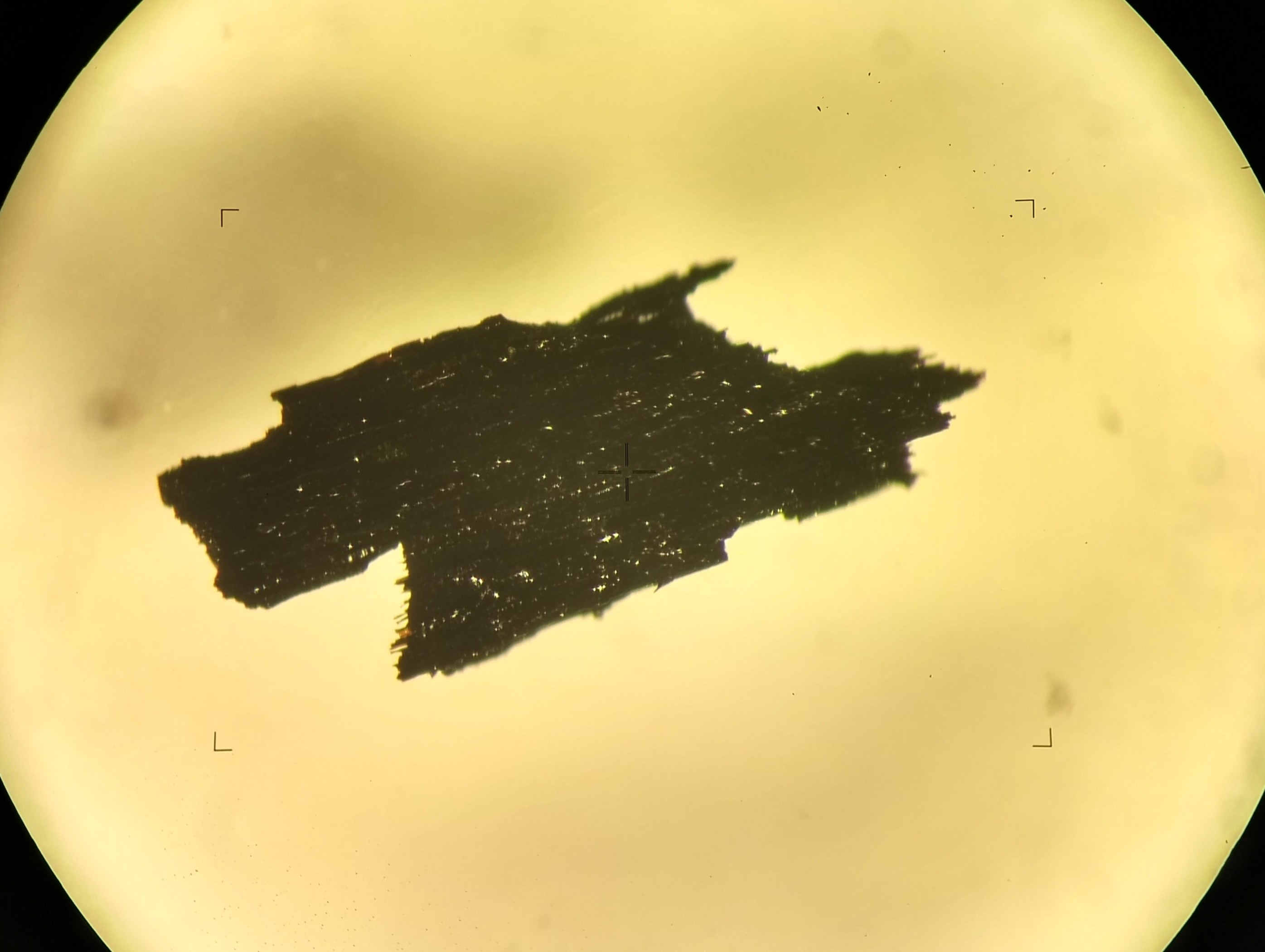

Some of these samples we used for an estimation of sediment organic carbon content and prepared them for a comprehensive radiocarbon age dating procedure. Once the resulting age estimates were available, statistical age-depth modelling could be applied to derive age estimates for all remaining samples, and a final selection of sediment core samples was done based on the quality of the corresponding chronologies. Samples from the selected eight sediment cores for the analysis of charcoal particles were then prepared in the laboratory, which included sieving the sediment and bleaching the remaining fraction for better optical contrast of the black charcoal to non-charcoal remains. Finally, each of the hundreds of prepared samples of sieved charcoal particles could be examined under a microscope (Figure 5) to count and categorize a total of multiple thousands of charcoal particles. These procedures are quickly described on paper, yet require some patience as a lot of time is spent in the laboratory and at the microscope.

Only once the quantification of charcoal samples was finished could the actual data analysis begin, described in our research paper in more detail. Thanks to the new data, we could reconstruct the first regional trend of biomass burning over the past c. 11,000 years for this region. In addition, a comparison to climate-driven simulations of burned area in a forest model was done. Without diving into the similarly comprehensive work behind running simulations in such a forest model, our comparison indicates that the past climate can explain these reconstructed long-term Holocene trends. Interestingly, however, it fails to do so for shorter-term trends during the past c. 5000 years. This finding and the accompanying evaluation of sources on Mid- to Late Holocene human activity represent the foundation on which our research paper proposes the need for a better understanding of the poorly reported human dimension of past fire dynamics in eastern Siberia. After all, our findings suggest that the indigenous Sakha may have successfully reduced the probability of severe wildfires around their settlements already hundreds of years ago. We assume that traditional land use practices such as the controlled use of fire, which is prohibited today, reduced fuel loads around settlements (the Sakha term өттөөhүн, for example, refers to the controlled burning of old grass). Having experienced the impacts of a fire season such as 2021, we believe that this human dimension, derived from a reconstruction of the past, has the potential of contributing to our understanding of how to best safeguard local communities in a rapidly warming world. Initially, however, this publication began with a coring device plunging into the sediments of a lake in eastern Siberia.

We would like to thank all other coauthors of the research paper for their contributions, and extend this acknowledgement to the principal investigators, expedition members, land owners, and everyone who supported this cooperative project in other ways among both the Sakha and German partners.

Follow the Topic

-

Communications Earth & Environment

An open access journal from Nature Portfolio that publishes high-quality research, reviews and commentary in the Earth, environmental and planetary sciences.

Related Collections

With Collections, you can get published faster and increase your visibility.

Climate extremes and water-food systems

Publishing Model: Open Access

Deadline: May 31, 2026

Archaeology & Environment

Publishing Model: Hybrid

Deadline: Mar 31, 2026

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in