Dams Make Fish Sick: A Journey from Curiosity to Discovery

Published in Ecology & Evolution and Zoology & Veterinary Science

An Observation in the Field

Over two decades ago, I was a student at the University of Tartu, aiming to characterise the genetic structuring of Atlantic salmon for my Master’s project. I joined the late Mart Kangur, who was responsible for national salmonid monitoring in Estonia, for fieldwork. It was a transformative experience. Mart possessed a vast knowledge of the biodiversity within our rivers and streams, yet he never shied away from admitting what he didn't know. It was the perfect environment for a budding scientist who wanted to know everything about rivers and fish.

Among the many observations was a curious case: after electrofishing, juvenile brown trout in certain streams seemed unable to tolerate even brief periods of hypoxia in a bucket before being measured. At that time, Proliferative Kidney Disease (PKD) was the suspected cause, though the responsible parasite remained an enigma, known simply as PKX.

Unmasking the Parasite and its Life Cycle

The mystery was resolved in 2000, when the parasite was taxonomically classified as Tetracapsuloides bryosalmonae and assigned to the newly established Malacosporea class, Myxozoan subphylum (1). It is essentially an ancient relative of jellyfish and hydras that committed fully to a parasitic way of life. This transition is permanent as T. bryosalmonae and other myxozoans have undergone extreme genomic reduction, shedding the genes their ancestors once needed for independent life. The scale of this "shrinking" is staggering. For perspective, the human genome is more than 100 times larger than that of typical myxozoan.

We now know T. bryosalmonae relies on a remarkable two-host life cycle that begins within freshwater bryozoans. These are tiny, moss-like colonial animals attached to rocks, concrete or submerged wood. Infected bryozoa release spores, known as malacospores, into the water, which enter salmonid fish primarily through the gills or skin. Once inside, the parasite migrates to the kidney and spleen, triggering a violent immune response and host cell proliferation when water temperature is high. This causes the kidney and spleen to swell, leading to severe anemia and potentially death. Interestingly, if the salmonid host survives until autumn and water temperatures drop, it usually recovers as the parasite moves into the kidney tubules without causing further pathogenic effects. The parasite’s cycle eventually closes when the infected fish releases different type of parasite spores (myxospores) back into the water via urine, reinfecting the bryozoan colonies.

Approximately ten years after those initial field trips, I returned to this mystery by launching one of my very first research projects to map the parasite's distribution in wild salmonids. As our team grew, this host-parasite system pushed our research into new frontiers. We adopted cutting-edge methodologies, such as eDNA to detect parasites in the water, QuantSeq to screen in cost-effective manner large number of transcriptomes and dual RNA-seq to simultaneously capture the genetic responses of both the host and the parasite. We mapped the parasite's occurrence across diverse habitats and quantified its impact on salmonid health, examining everything from oxygen intake and thermal tolerance to oxidative stress, telomere length, and microbiome communities (2-6). This parasite also helped us to bridge multiple disciplines. For example, we utilized quantitative genetics to estimate the heritability of parasite resistance in wild trout and combined mark-recapture techniques with transcriptomics to measure how disease-driven natural selection shapes gene expression (7-8).

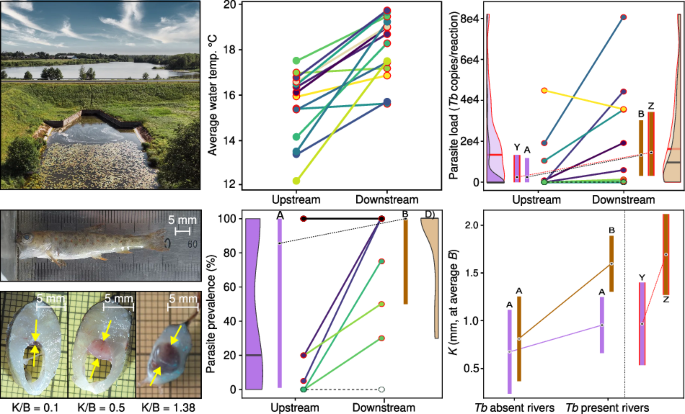

Yet, one nagging observation remained: the most severe PKD outbreaks were consistently occurring downstream of dams. Given that PKD is highly temperature-dependent and that nutrients boost bryozoan growth, it became clear that man-made dams, through warming and nutrient enrichment, might play a direct role in triggering the disease. To confirm this, we needed to study fish and disease systematically both above and below these obstacles. Finally, after several unsuccessful grant proposals, we carried out two field seasons in 2022–2023, sampling trout populations across 14 different dams in Estonia to measure disease traits and quantify parasite loads.

Dams Trigger Disease

The results of the two-year field campaign confirmed what we had long suspected. As it turns out, surface-release dams act as giant solar heaters. By releasing the warmest top layer of the reservoir into the river below, these structures create artificial thermal hotspots. In some cases, the measured water temperature was up to 4–5 °C warmer downstream the reservoir. These warmed sections turn into ideal environments for the malacosporean parasite, leading to consistently higher infection prevalence and greater parasite loads compared to upstream sections.

This creates a 'thermal disease trap': when water gets warmer, fish need more oxygen to survive, but warm water holds less dissolved oxygen. Warmer water also fuels parasite proliferation and accelerates disease progression, making salmonids anemic and less capable of extracting oxygen from their environment. It is a deadly double-whammy, as the peak of clinical anemia coincides with the seasonal period when oxygen availability is lowest and physiological demand is highest. Because of severe PKD, a large portion of young trout may not survive the warm summer in these heated river sections.

A New Paradigm for River Management

Our study published in Communications Biology suggests that dams are creating localized thermal environments that essentially fast-forward the effects of global warming (9). While river restoration activities often focus on dams in terms of blocking migration (habitat fragmentation), fish biologists have largely overlooked their role as drivers of disease. Thus, to safeguard salmonids in a warming world, our approach to river management must change. Given that surface-release dams are ubiquitous across global river networks and many fish diseases show temperature-dependence, it is critical that we formally incorporate the risk of temperature-driven disease into environmental impact assessments. Removing obsolete dams isn't just about opening migration routes, it's also about keeping the rivers cool and clean to curb disease progression.

This journey reminds us that to protect the rivers, we must understand biological interactions between the environment and organisms. Science often starts with a simple observation that something isn't quite right, followed by the quest to find out why.

References

1. Canning EU et al. (2000) Diseases of Aquatic Organisms, 41(2), 115-123.

2. Dash M, Vasemägi A (2014) Diseases of Aquatic Organisms, 109, 139-148.

3. Bruneaux M et al. (2017) Functional Ecology, 31, 216-226.

4. Stauffer J et al. (2017) Oecologia, 185(3), 365-374.

6. Vasemägi A et al. (2017) mSpere, 2(6) e00418-17.

7. Debes PV et al. (2017) American Naturalist, 190(2), 244-265.

8. Ahmad F et al. (2021) Molecular Ecology, 30(12), 2724-2737.

9. Lauringson M, Näslund J, Pukk L, Kahar S, Gross R, Vasemägi A (2026) Dams threaten salmonids by triggering temperature-dependent proliferative kidney disease. Communications Biology, https://doi.org/10.1038/s42003-025-09470-1

Follow the Topic

-

Communications Biology

An open access journal from Nature Portfolio publishing high-quality research, reviews and commentary in all areas of the biological sciences, representing significant advances and bringing new biological insight to a specialized area of research.

Related Collections

With Collections, you can get published faster and increase your visibility.

From RNA Detection to Molecular Mechanisms

Publishing Model: Open Access

Deadline: May 05, 2026

Signalling Pathways of Innate Immunity

Publishing Model: Hybrid

Deadline: May 31, 2026

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in